Koalas are the wildlife icons of Australia. Along with kangaroos, they’re probably one of the first animals that comes to mind whenever a nature nerd thinks about the land down under.

But what many people don’t know is that the koala was almost hunted to extinction last century. Like the beaver in North America, koalas were killed by the millions for their fur. That is, until American President Herbert Hoover helped put a stop to the trade.

Killing Koalas By the Millions

In the late 1800s and early 1900s, fashion was the enemy of wildlife. Trappers killed beavers by the tens of millions to turn their pelts into hats, and plume hunters slaughtered tens of millions of North American waterbirds to decorate women’s headwear.

Across the Pacific, a similar carnage was unfolding in Australia. From the late 1800s to the 1920s, the world went crazy for koala fur. It was tough, warm and waterproof, so like beaver pelts they were in high demand to make hats, gloves, and coat liners for consumers in London, the United States, and Canada.

Scientists think that koalas were uncommon when Europeans first arrived. Settlers encountered and described most of the other large mammals in eastern Australia — like kangaroo, dingo, quoll, and possums — almost immediately after settling modern-day Sydney in 1788. But it took another 10 years before the first European saw and recorded a description of a koala, and the species wasn’t formally studied or described for almost 30 years.

Aboriginal peoples hunted koala, and scientists think that this pressure kept the population low but stable. When Europeans arrived they devastated Aboriginal populations, relieving hunting pressure and allowing koalas to increase.

By the late 1800s koalas were abundant, valuable, and all too easy to kill — a deadly combination.

Richard Semon, a German biologist, wrote about his experiences shooting a koala in 1899:

“My shot wounded the creature … it hung for some time suspended by its fore-paws, and trying in vain to draw up its hind- paws, and so swing itself on to the branch. … I aimed once more, and struck its head and left forefoot. Still it clung to the tree for a while with its right fore-paw, then fell down heavily, and died a few minutes later. It was a strong fully-developed female, carrying a half-grown young one on its back. The poor little thing clung to its dead mother with its sharp paws, and would not be torn away. I thought of taking it into my camp and rearing it, but the next morning it had left its mother’s cold body and disappeared.”

The scale of the slaughter was immense. Reliable data is difficult to find, but researchers estimate that 450,000 to 500,000 koalas were killed each year between 1903 and 1906. (No records exist prior to the early 1900s). After 1906, the harvest increased to an estimated 450,000 to 1 million skins per season.

Any one of these annual harvests killed more koalas than are alive today.

Unsurprisingly, the population couldn’t sustain this level of hunting and koala numbers plummeted around the country. By 1912 koalas were functionally extinct in South Australia, meaning there were so few left in the wild that the population was no longer viable. About a decade later they were nearing functional extinction in New South Wales, and just 500 to 1000 remained in all of Victoria.

Black August

By the early 1900s, hunting decreased in many states simply because there were just too few koalas left to kill. State governments passed legislation either protecting koalas or limiting hunting, often too late. For example, South Australia passed koala protection laws in 1912, the same year they went functionally extinct.

But in Queensland — where koala populations were still moderate — hunting continued for another two decades despite legal protection. These regulations banned hunting except during designated “open seasons” every few years, but researcher Glenn Fowler says that the ban was difficult to enforce and often ignored or evaded.

Public support for koala protection began to grow after Queensland’s 1919 open season, according to Fowler, during which 10,000 licensed trappers obtained more than 1 million koala pelts in 6 months.

Eight years later, in 1927, the Queensland government allowed a final one-month open season on koalas. Outcry from scientists, conservationists, and the general public was not enough to stop it. The state had just suffered a crippling drought, and Fowler writes that the government chose to allow koala and possum hunting in a deliberate effort to both boost rural employment and secure votes to keep their political party in power.

By the end of Black August, as the month became known, hunters sold nearly 600,000 koala pelts. But historians estimate that the true death toll was likely closer to 800,000 animals, because that figure does not include dead joeys, spoiled pelts, or koala fur sold as a different animal to thwart regulations. Historians also suspect that many of these animals were hunted illegally in advance of the open season.

At this point, extinction seemed inevitable. So with the fate of the species at stake, Australian conservationists took action with help from an unlikely hero: US President Herbert Hoover.

Herbert Hoover, An Unlikely Hero for Koalas

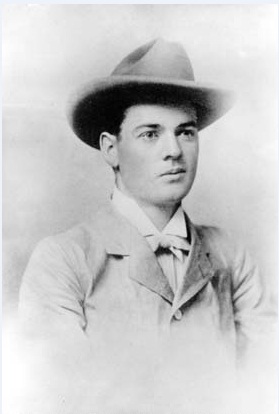

Before politics, Herbert Hoover made his fortune in the mining industry. At the age of 23 he went to work for the London-based company Bewick, Moreing & Co., which owned gold mines in Western Australia. Stationed on the edge of the Great Victoria Desert, Hoover described arid Australia as land of “black flies, red dust and white heat.” He traveled extensively throughout Australia for several years, before marrying and moving out of the country.

By 1930, Hoover was one year into his term as President of the United States. That year, the Wild Life Preservation Society of Australia contacted Hoover to tell him about the crisis facing the koala. They also asked him to ban the import of both koala and wombat skins into the US, eliminating a major market.

Hoover agreed, likely saving the koala from future open seasons and probable extinction. Some sources speculate that his time in Australia made him sympathetic to the koala and motivated him to sign the legislation. Three years later, the Australian federal government followed suit, banning the export of koalas and koala products.

An Uncertain Future for Koalas

The fact that koalas are still here today is a conservation victory. But koala populations have never recovered from hunting, and now new threats are causing their numbers to decline once again.

Scientists estimate that there are about 329,000 wild koalas in eastern Australia — which is less than one year’s annual harvest during the fur trade years. Part of the problem is koala biology: females raise just one joey at a time and don’t often breed every year.

But now widespread habitat loss is causing koala populations to decline once again.

Australia is a global deforestation hotspot, with deforestation rates on par with places like the Amazon or Congo Basin. Most of this land is cleared for agriculture, grazing, or urban development. And where there are people, koalas are at risk of being hit by cars or attacked by dogs.

Most of the remaining high-quality koala habitat is on private land, not protected areas. And what habitat does remain is increasingly plagued by devastating bushfires, which climate change is making both more intense and more frequent.

As a result, a majority of koala populations are in decline. For example, a 2016 report found that koalas around Brisbane declined by 80 percent in just 20 years. Without action — protecting large swaths of connected koala habitat — these charismatic little marsupials are once again sliding towards extinction.

It’s a grim thought, but hopefully history won’t repeat itself.

Join the Discussion