Four women walk through a meadow of green, knee-high grass with white gauze nets in their hands. Three are interns, one is an expert, but all of them are looking for butterflies. Not the orange painted lady variety that fools wing watchers often, but monarchs. Monarchs are larger, more vibrant and less abundant.

The crew is working within Idaho’s Curlew National Grassland, barely a handful of miles north of the Utah border. It’s the biggest monarch butterfly breeding site the U.S. Forest Service manages in the Intermountain West. While eastern monarch butterflies fly south to Mexico for the winter, most western monarchs migrate to the California coast. The netters at Curlew try to tag them en route.

“It’s amazing really,” says Rose Lehman, Caribou-Targhee National Forest botanist. “Butterflies are only the weight of a paperclip and yet you can put this little sticker on them and hope that someone sees it and reports it.”

Lehman estimates she needs to tag at least 200 sunset colored wings for the slim chance of having at least one seen and reported. The netters don’t have 200. They’re empty-handed in the state with monarchs as its official state insect.

Monarchs coming from Arizona, California, Idaho, Nevada, Oregon, Utah and Washington are missing. The void is alarming. Migrating western monarch butterflies declined 85 percent from 2017 to 2018. The current count is 28,429 monarchs collecting on the Pacific coast this winter. That’s down from an estimated 4.5 million in the 1980s.

“There’s funding for emergency research and we’re using it now,” says Emma Pelton, Xerces Society conservation biologist. “Our worst fear is monarchs totally disappear before we figure out why they’re disappearing.”

U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service launched a monarch conservation database last summer. It’s considering the addition of monarchs to the Endangered Species List this year. A decision is expected in June.

Researchers predict population collapse at 30,000 butterflies. Monarchs are below that now, but don’t throw your hands in the air of despair yet. Natural Resources Conservation Service, within the U.S. Department of Agriculture, offers more than three dozen ways large-scale growers can help monarchs. Individuals on a small scale have a hand in recovery too. What you plant in your garden and flowerbeds this growing season will help or hinder pollinators, including monarchs.

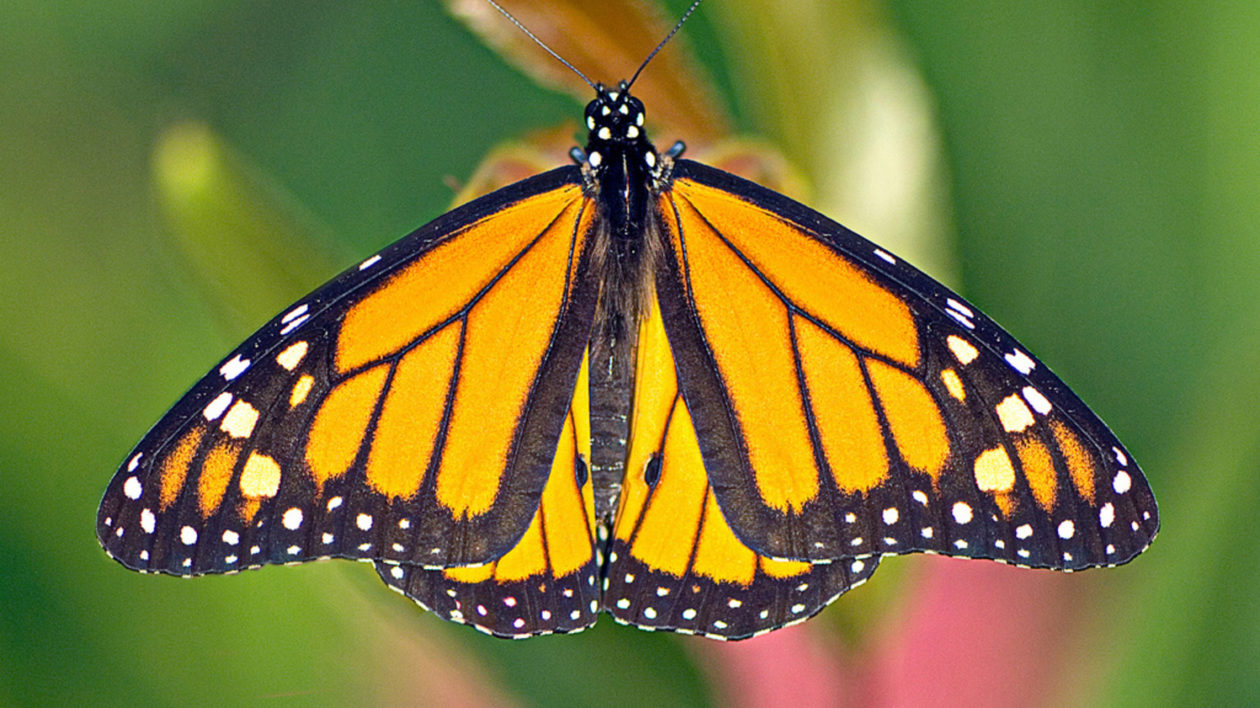

As caterpillars, monarchs display sharp stripes of yellow, black and white while creeping along the leaves of milkweed, feasting as they go. As adults, they’re delicate triangles of orange-veined with black, floating on the breeze in search of nectar. They’ll search your yard for it.

“So much of our food and human condition is dependent on pollinators,” Lehman says. “Certainly everybody can be more aware of what they plant in their garden and make sure it’s pollinator friendly. There are a lot of things individuals, and natural resource managers alike, can do.”

What you do is not as simple as planting any and every bloom. Choose specific blooms for butterflies. Tulips, for example, are bred for beauty rather than food for insects. They won’t help the butterfly population, but milkweed will. So will pollen producing plants like aster and goldenrod.

That’s what you want, but before you buy, ask the nursery if the plants have been treated with insecticide. There’s often poison applied to protect plants from leaf-eating bugs and it’s expressed in nectar and pollen. It kills insects, including bees and butterflies. Consider how many gardens butterflies fly over when winging it across the West. Reducing insecticides in those gardens could increase the monarch butterfly population.

“Monarchs are conservation ambassadors because they migrate over huge areas,” Pelton says. “You have to conserve habitat among a lot of different people over a lot of different landscapes.”

They are drawn to the Curlew National Grassland, ironically enough, for invasive Russian olive. Some of the silver-leafed, fragrant trees are falling on the ax as part of a multi-year, major, landscape restoration project, but not all of them. Monarchs seek the shade of Russian olives along riparian areas, the wet zones, when crossing the desert on hot, summer days.

“Russian olive is a weed,” Lehman says. “But removing that structure is a challenge in the management of monarchs.”

The other challenge is time. Time is running out on resolving the butterfly’s rapid decline. On the upside, bugs breed a lot faster than big game.

“This is not the story of slow, reproducing megafauna,” Pelton says. “We’re not talking about one egg here. We’re talking about hundreds of eggs and that can yield fast results. And these are not animals in remote places. Any person, even if they rent an apartment, can set out a pot on their stoop with a plant in it that attracts pollinators. Everyone can help.”

If you want to give monarchs a hand in your own yard, here’s what to plant.

- For spring nectar: Native milkweed, Culver’s root, beach blanket flower and native thistle. Planting native milkweed (not tropical milkweed) is encouraged unless you live along the California coast. Do not plant milkweed within five miles of the coast. It disrupts overwintering monarchs during their rest cycle.

- For summer nectar: Sunflowers, bee balm, blazing star.

- For fall nectar: Aster, goldenrod, rabbitbrush, coyote bush.

Not sure if it’s true but I heard that they have opened the monarch “park” up to the public and people are trampling over them.

We bought 3 milkweed plants because last year we saw no Monarchs. Within a month there were 4 caterpillars on the bushes. After days of eating 2 made cocoons near the plants, another one headed for a big India Hawthorn hedge nearby, and one disappeared overnight. A week later there were 4 more! After a few days of eating 3 disappeared overnight, 1 made cocoon near the milkweed. On May 1st we saw a pair of Monarchs in flight 1/2 a block away – a joy. We live on a hill in Ocean Beach/San Diego 4 blocks from the ocean. We know almost nothing about Monarchs but we love them. We keep a small overgrown pesticide free garden. We don’t know how long they will be in cocoon, or which direction they are traveling. We will plant the pollen bearers listed in your article & try to educate ourselves. Thank you.

Thank you for the informative article. It seems those of us who live at the beach, we are in Venice Beach, California, get confusing information about planting milkweed versus not planting milkweed. My understanding is we should plant native milkweed but not tropical milkweed at the coast. This article seems to be saying we shouldn’t plant any milkweed within 5 miles of the coast. My neighborhood is full of tropical milkweed. People are planting all kinds of milkweed like crazy and we’ve had lots of monarchs and caterpillars all spring summer and fall. The only time we don’t see them is in the winter.

I remember seeing monarchs as a child in Venice (50 years ago!) So there must have been milkweed around at that time as well. Is there someone who can clarify this milkweed versus no milkweed at the beach question?

Thanks!

We planted milkweed in our garden and the first year we had many monarch caterpillars that became butterflies. The following year we had plenty of monarchs visiting our milkweed plants but had very few caterpillars. I also noticed an increase of those little lizards that have invaded Cincinnati in my garden. Could it be that they are devouring the monarch eggs and caterpillars?

I planted the tiniest sprig of milkweed in late summer, hoping for it to be thriving by spring. Wasn’t expecting to find a cat on it in February, but guess what? Took her in and two days she emerged looking fine and healthy. My concern is that it’s been below 60 and I’m concerned about releasing in this cold snap.

Anyone have idea about whether its safe to release (she has different food options, a net “condo” and plenty of warm sunlight inside) or hold on for a few more days?

I’m in Anaheim, CA

eenglandfc@gmail.com

I have heard so much about Monarchs in the last year or so that I am thinking of going to an Organic nursery or something similar and ask people to plant Milkweed in their gardens.

Also, I like that you mentioned if you rent an apartment you can plant milkweed in a pot and put it outside to attract Monarchs. I may do that and tell other people I know to do that too.

Any other suggestions from you would be great. The best way to reach me is by email or you can provide a phone number and I can call you.

Thank you,

Alan Solomon

asolomon777@gmail.com

Article said: “the Natural Resources Conservation Service offers more than three dozen ways large-scale growers can help monarchs.” Well I visited a native milkweed farm west of Sacramento, Calif. on June 3, 2018 when their giant sized field of planted speciosa milkweed was in full bloom. But I only saw one monarch and no caterpillars. Then on July 8 I visited their giant sized field of planted fascicularis

milkweed that was in full bloom and once again saw only one monarch and no caterpillars.

Here’s a 2 minute video documenting my June 3 and July 8 observations:

https://youtu.be/4RlDrnd8Ank So planting milkweed – even massive quantitites of it – doesn’t look it will “recover” the western monarch population.

I received some milkweed seeds from my Uncle in Washington State.

The prison group there has worked on the Monarch as a project.

I did some research on the milkweed plant and remember my childhood days collecting the pods.

They were sent to the government to make life preserver vests for the military during WW11.

It was a school project and prizes were given for the most collected by any school.

I believe over 10,000 vests were made since the source of the normal material was cut off by the Japanese I believe.

Back to the butterfly, I am going to try again to get my seeds to grow this year.

Love the article.

Its downright scary that last summer as with summers before I saw

two TWO monarch butterflies! This is in NYS in summer – where

there used to be so many. Its the same with bees – so few. A few

years ago I had sphinx moths on my bee balm – none last year.

This is so very important – people need to be made more aware

that these creatures are necessary in order for US to remain alive!

Its sad to hear that restoration projects removing an invasive tree end up removing monarch habitat. I wish we could focus on restoration and conservation projects that are win-win instead of win-lose.