Some call it a green hell: As the invasive cactus species Opuntia engelmannii spreads in Kenya, it covers everything. It spreads across the plain and outcompetes native plants. Formerly diverse habitats are now nothing but cacti. The species even covers bare rocks. It attracts both wildlife and cattle with its sweet fruits, but also can hurt or even kill animals with its numerous thorns.

The Loisaba Conservancy is 56,000-acre community-conservation project, known for its thriving wildlife, sustainable cattle ranching and ecotourism. It also has an invasive cactus problem, with an estimated 20 percent of the conservancy covered in the plant.

It’s spreading fast. To address the problem, land managers need to understand exactly where the cactus is growing on the conservancy. As the plant forms thick, impenetrable thickets, that’s a nearly impossible task on foot or even by vehicle.

Gustavo Lozada understood the difficulties of monitoring the cactus the moment he saw the plant while on a vacation in Kenya. But he also immediately began thinking of solutions. You see, Lozada has earned a reputation as a “drone master” in his technology work for The Nature Conservancy in Colorado. He has used drones to map vegetation and habitats and developed non-intrusive methods to use them to research wildlife. Perhaps he could use his technological prowess to help with the invasive cactus.

The Cactus Farmer’s Son

The moment Lozada saw those cacti, it brought back childhood memories of his Venezuelan home. His father was a civil engineer but at one point started raising prickly pear cacti as a side hobby.

“He wasn’t doing this to produce cactus, but rather for cochineal insects that feed on the cactus,” says Lozada.

Lozada says these insects resemble “fat dog ticks” and they behave in a similar fashion. The cochineal insect attaches itself to the cactus, where it will remain the rest of its life. It sucks all the nutrient-rich red liquid from the cactus. The insect bloats with the red liquid, and this is what was harvested by Lozada’s father.

The red liquid is used as an organic dye for clothing and even food. The recent controversy over Starbucks using bugs to as coloration for its beverages? That was cochineal insects.

His father’s career as a cactus farmer didn’t go very far, and he abandoned the project after a few years. But Lozada immediately recognized the plant and was astounded by just how invasive it became outside its native range.

“It had no competition at Loisaba,” he says. “It was just completely out of control. Where it grows, there’s nothing else. You could see new cactus emerging beneath native bushes. Soon it overtakes and suffocates all the other plants around it.”

No one knows for sure how the cactus came to Africa, but the most likely source was European colonists who planted the cactus as ornamentals or “living fences” 60 to 80 years ago. “You will still see small farmers using the cactus as a fence to keep out wildlife,” says Lozada.

It should be noted that there are a variety of introduced prickly pear cactus species in Kenya, and not all of them are invasive. A few are useful and grown commercially.

But the species Opuntia engelmannii has continued to spread, sometimes abetted by people attempting to kill the plant. “If you cut it off at the base, the cactus will come back stronger than ever,” Lozada says. “If you leave one little fragment of cactus, the whole population can rebound.”

The cactus thorns choke out native grasses, depriving wildlife of food. And the invasive plants have even been documented irritating and even killing wildlife and cattle. “If you touch the fruit, you get covered with thorns and they are really difficult to remove,” says Lozada. “I can’t imagine what it’s like for a cow or even an elephant to get a mouthful of these.”

Still, many wild animals are drawn to the sweet fruit. And some animals – like baboons, elephants and tortoises – readily ate it and spread the seeds. Slowing the cactus invasion appeared a tall order without an effective control.

As he looked upon that “green hell,” another thought came back to him from his youth: What about those cochineal insects? After all, there are species of these insects that suck the cactus dry, leaving nothing but a dead husk.

“It looks like the cactus is melting,” says Lozada.

Mapping Cactus

Just as Lozada surmised, the cochineal insects are an extremely effective biocontrol. There is one species that evolved to feed specifically on Opuntia engelmannii, so there was no risk of them spreading to native vegetation. This insect has gone through the National Environmental Management Authority process that identifies risks of biocontrol. The process found no negative effects and determined that the use of biocontrol is more effective than herbicide. The cochineal insect is officially approved for introduction in Kenya.

Since the insect only feeds on Opuntia engelmannii, when the invasive cactus is gone, the cochineal insect will simply die off.

The Loisaba Conservancy was preparing to deploy the biocontrol insects. But how would conservationists know if it was effective? After all, the full extent of the spread had not been mapped.

Lozada knew he could help. He knew the drone work he had done with The Nature Conservancy in Colorado could also be applied to this problem in Kenya. Tom Silvester, CEO of the Loisaba Conservancy, and Matt Brown, director of The Nature Conservancy in Africa, were both enthusiastic supporters of Lozada’s work.

Lozada received a Coda Fellowship, an internal Nature Conservancy program that provides short-term assignments to meet TNC’s global needs, while also providing staff with professional development opportunities. Many staff (including me) have benefited from this great program, and it has also led to creative solutions for conservation challenges around the globe. Like invasive cactus.

“I thought we could establish a baseline of what is there,” says Lozada. “This would allow managers to assess the effectiveness of the cochineal insects.”

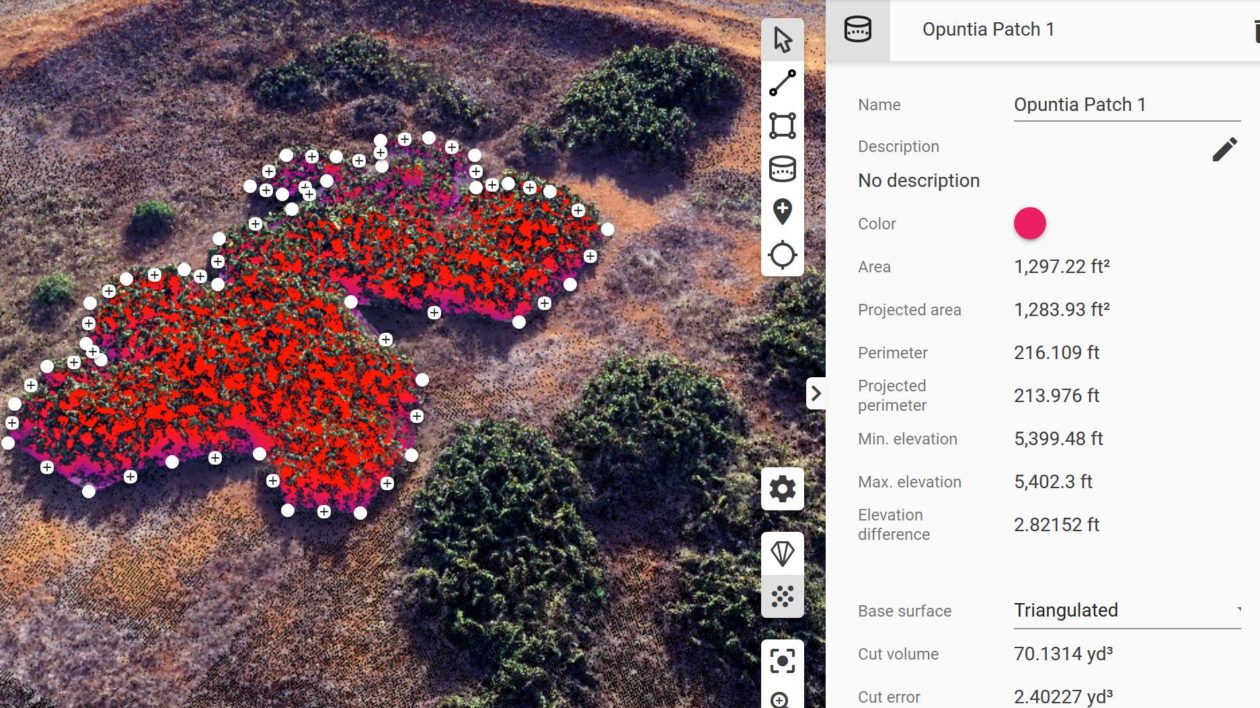

Enter the drones. Lozada headed to Loisaba and began mapping the cactus. The drones are programmed to fly a grid, taking hundreds of images they fly. “Each picture contains a lot of data,” says Lozada. “I use that to created three-dimensional models that provide detailed information on the presence of cactus.”

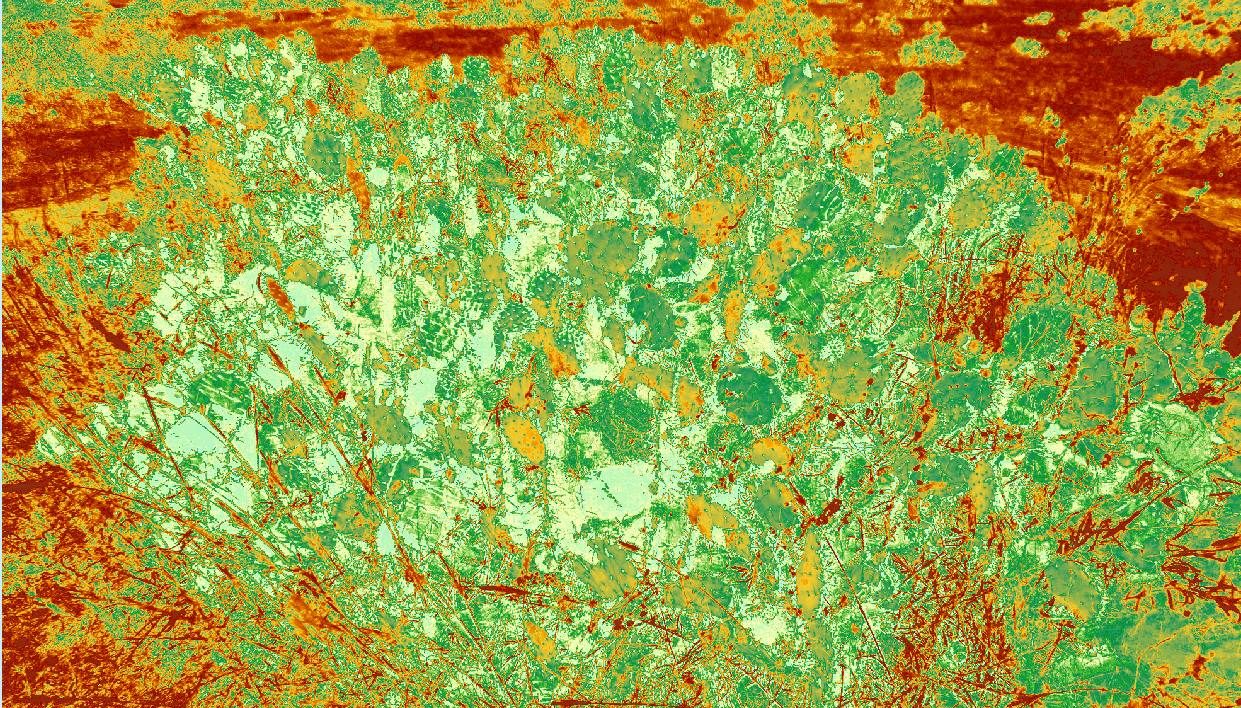

Lozada analyzes three layers of data. First, the drone’s imaging detects the reflection of green. The greener the plant, the brighter it shows up on the screen. This imaging can pick up subtle differences in greenery. (Farmers use it to determine where fertilizer was most heavily applied on a cornfield, as more heavily fertilized corn stalks will be slightly greener).

In the dry season, prickly pear cactus is one of the few green plants, which makes mapping it much easier.

The drone also allows very precise mapping of the invasive plants. “I can zoom down to a tiny rock and see a cactus growing on it,” Lozada says. “I would do this to verify the accuracy of the mapping.”

The data can also map the volume of cactus in any given acre. “The first thing affected by cochineal insects is the volume of plants,” says Lozada. “So having this data will be very important in tracking the impacts of the biocontrol.”

It can be difficult for land managers to understand the full scope of an invasive plant. Terrain and the density of vegetation routinely foil the best-laid plans. The drone can thus change management considerably. Now people can accurately map the full extent of the spread, monitor the effectiveness of control measures, and adjust plans to best control and eradicate the plants.

“We often hear about the misuses of drones,” says Lozada. “But drones can be tremendously effective conservation tools. A landscape covered in invasive cactus can seem like an impossible problem to address. You have to understand the problem before you can address it. The drone provides the most accurate information, allowing us to stop this nasty threat to wildlife and livestock in Kenya.”

Great to hear they are working to eradicate this cactus. I know how tenacious it is and how easily it spreads. While I like it in its native habitat, it does not belong beyond the ecosystem in which it evolved. I dread the thought of it growing in a place like Africa. Keep up the work!!

I enjoy Matthew’s articles and reporting. And also his list of nature mystery novels and stories. Thank you

I want to add that Silver Creek was also my late husband’s favorite fly fishing water. Thus it is mine too and the focus of my charitable giving to TNC

Valerie,

Thank you for the kind words and thanks for your support of Silver Creek. It is a special place; I have so many great memories there.

Best,

Matt

Fascinating and fantastic discovery

Thank you for publishing this inspiring article. Free

After mapping, can the drones be used to drop the insects into the cactus patches. Especially those in hard to reach areas. Seems like an extremely effective way to address the issue.

I grew up in Australia where the Prickly Pear (Opuntia) population was expanding and denying cattle grazing. Introduction of the Cactoblastis (moth I think is was) was successful and an excellent example of bilogical control. Mapping helps Good luck with your work

I did not notice any mention of the problems Australia had with this plant. It literally drove people out and closed down whole towns.

The Australians tried flamethrowers to get rid of it. That did not work. They got it under control with insects.

There are still prickly pears growing in Australia but it is no longer an epidemic.

Fraptious day! Now find a market for the dye. How often does invasive control pay for itself?

It would be really great if this would work and be adopted to manage this invasive species that has ruined vast areas in Laikipia North cripling the livestock industry that plays an immense role in the livelihoods of people there.

Have they tried cactoblastus cactorum? It sorted Australia prickly pear problem

One man’s meat is another man’s poison, according to the poet Lucretius. I’ll think of this as I scrape the cochineal off of the opuntia around my place in Tucson, Arizona, and watch Desert Spiny Lizards eat the flowers, and a variety of birds, rabbits, javelina, and squirrels eat the fruit and other plants parts.

I couldn’t agree more, also being from the Tucson area. It’s hard to believe prickly pear could injure cattle, considering that here, cattle eat them all the time and have quite a negative impact on them. So in Africa they are trying to eliminate prickly pear and here in the southwest we battle Africa’s invasive buffel grass. Too bad there is no biological tool to kill the buffel grass. Crazy….

Is the cactus infected area where elephants occur? In Addo Elephant National Park (South Africa), elephants preferentially feed upon wheel cactus – to the extent that they almost eliminated cactus from the area before lions were reintroduced. The spread of Opuntia might be a side effect of reduced elephant densities throughout Africa.