I have a confession to make: nearly a decade into my birding career, I still can’t identify birds by ear.

I know a handful: the cry of a Red-tailed Hawk or the peterpeterpeter of a Tufted Titmouse. But that’s just luck more than anything else. (If I’m still getting confused by American Robins, I don’t know my bird calls.)

It wasn’t hard to hide my secret from other birders. I have a sharp eye and could rely on a decade of visual-ID experience, so I didn’t really need to know birdsong. But all that changed when I moved to Australia a few months ago.

Suddenly I was a complete novice all over again. Entire 30-page sections of the field guide might as well be in Greek. What the heck are babblers? Or trillers? Or gerygones? In those first months, it took me an average of 10 minutes of frantic page-turning to identify a single bird.

Experienced birders rely on a range of subtle visual clues — learned through experience — to help make their ID: how the bird is foraging, or its posture when perched, or the pattern of its wingbeats in flight. And, of course, its call.

Now I have to re-learn everything, and I need to use every single tool at my disposal. So I decided that once and for all I was also going to learn bird calls. Or die trying.

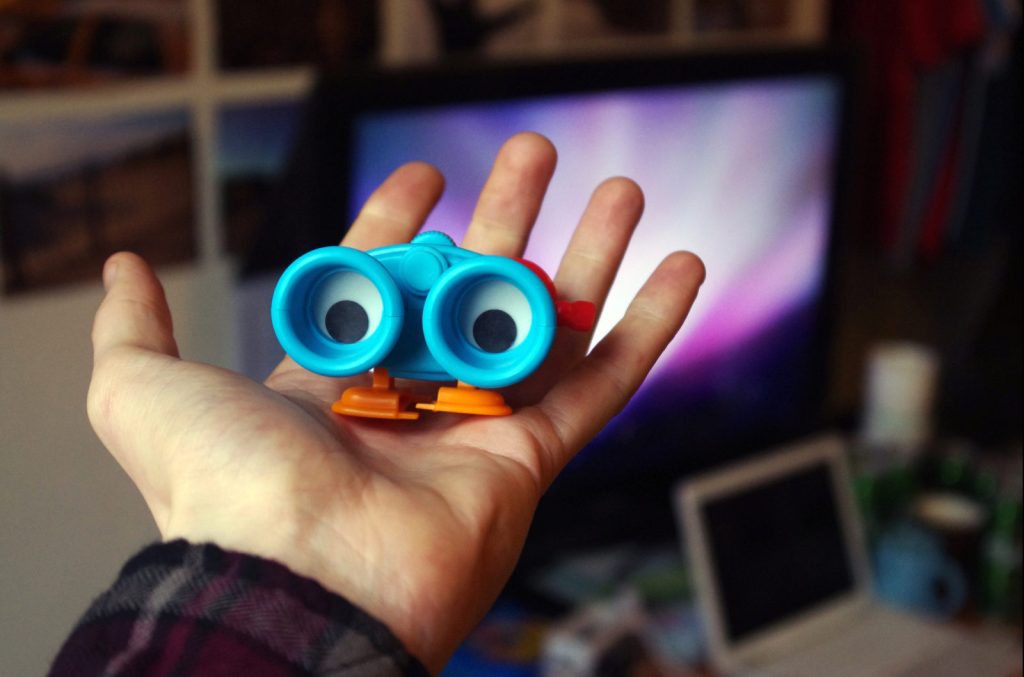

Through the Binoculars Darkly

It’s 6:00 on a Sunday morning and I’m awake, caffeinated, and ready to bird.

Overcoming my auditory avian incompetence is no easy feat, so I recruited the best Australian birder I know, Hugh Possingham, who also happened to be Chief Scientist of The Nature Conservancy. Hugh has five decades of experience and describes his own birding obsession as a psychological disorder.

Little did I know what I was getting myself into.

Hugh is leading a group bird walk at his favorite local hotspot, Oxley Creek Common, in suburban Brisbane. As the khaki-clad birders start assembling in the parking lot, I joke to Hugh that the only way he’s going to get me to learn to bird by ear is to take away my binoculars.

“Okay,” he says. I laugh, but it dies in my throat when I realize he’s serious.

“That’s it, no binoculars allowed.”

I stand, speechless, as Hugh walks off and starts herding the nerds into formation. What have I just done?

Hugh reviews our route for the day and informs us that we’ll be paying special attention to bird calls on this walk. “For every bird there are 10 birds calls, so it shouldn’t be called bird watching, it should be called bird listening,” he says. “Okay, we’re ready to go. Is everybody happy?”

No. I am not happy Hugh. Not happy at all.

With my binoculars still around my neck, I negotiate a set of rules that aren’t quite as strict as I’d feared, but are still annoying. I am allowed to use my binoculars, but only….

- After I stop and listen to the birds around me, making an honest effort to identify every sound

- If we’re identifying a bird that’s far away or not vocalizing

- When Hugh isn’t looking

Yes, you’re darn right I’m going to cheat.

One Bird, Two Bird, Red Bird, Figbird

I don’t even need my binoculars for our first two birds, because I know them by sight already: an Australian Ibis — colloquially known as a “bin chicken” for their habit of rummaging through urban trash cans and making a nuisance of themselves — and a Pied Currawong.

I actually know the currawong call, because one particularly noisy individual lives outside of my apartment building. Only this currawong is staying silent, sneaking along a casuarina branch and preparing to disembowel some unsuspecting skink.

Hugh hears a rosella — a large and colorful parrot — calling far across the field. Then a Channel-billed Cuckoo flies overhead, a grey bird with a beady red eye and a massive, eagle-like bill. I hide at the back of the group and whip up my binoculars. It’s not making a noise, and it’s a new species for me, so it’s fair game.

“That’s strange, they’re usually very loud,” says Hugh, and on cue the cuckoo erupts with a raucous ee-awk eee-awk ee-awk. “See, you don’t even need your eyes!” Yea, okay, sure.

We see and hear more birds as we walk: Pacific Koel, Rainbow Lorikeets, and Australasian Figbirds everywhere. I decide to take on the figbirds: they’re making a lot of noise and the call seems fairly consistent, so I walk along muttering to myself in an effort to memorize it. Tu-heer. Tu-heer. Okay, I think I’ve got this. Tu-heer.

We walk on, scanning the eucalypt trees and pasture for any signs of movement. The cows — which Hugh calls “Cattle Egret attractant devices” — chew their cud lazily in the shade. A dozen monarch butterflies flit across the meadow.

Tu-tu-heer. Tu-heer. Whatever it is, it’s right above my head. Trying to be a good pupil, I listen closely and don’t look up. “Hugh, what’s that!?” I ask. He stares at me witheringly, and I have the growing sense that I’ve done something wrong. “It’s a figbird. Again.”

Humiliated, I slink to the back of the group to use my binoculars, ogling the fairy-wrens like an addict scoring a hit. Give me that sweet, sweet magnification. I’m genuinely trying, and this is not going well. If I can’t even remember a figbird call for 3 minutes, how am I going to remember it forever?

But then I hear something familiar. I don’t know what bird is making the sound, but I definitely recognize the noise as one of the birds that wakes me up at the crack of dawn, which in the Australian summer is a horrifying 4:30 am. “There’s the Grey Butcherbird,” someone says. Oh, so that’s the jerk. Noted.

Buoyed by this small success, I work my way back up front to stand with the over-eager photographers, who are either cradling their camera like a newborn or wielding it like an AK-47. A Torresian Crow wails grumpily overhead. I know that one, too.

Then Hugh picks out the chirps of a Striated Pardalote high in the tops of a eucalypt. These tiny, spotted little birds are one of my favorites, but I rarely see them. “If you find an old eucalypt tree, chances are there’s a pardalote at the top,” he says, “but you’d never know it unless you hear their call.”

I’m starting to realize, grudgingly, that he has a point. I always considered birdsong an unnecessary bonus; handy in the rainforest, but superfluous for day-to-day birding. But if I want to see all of the birds that Australia has to offer, I’m going to have to get serious about birding by ear — even if it means using my binoculars less.

What Do You Mean I Have Homework?

Later, back at the carpark, we tally 72 species for the day. I managed to see almost all of them, through a combination of Hugh’s patience and blatant cheating. But my ordeal wasn’t over, because Hugh assigned me homework. Of course.

Assignment #1: When birding, search for sounds first and try to identify the species they belong to.

Assignment #2: Record 15 minutes of the dawn chorus at my apartment and try to identify every bird sound in the recording.

For other birders wanting to hone their listening skills, I’m going to suggest those same tasks. Bring your beloved binos, but listen instead of look. When you hear something, work backwards from the sound to the species.

Another trick is to use mnemonic devices to help you remember a species’ call… look in your bird guide or make them up yourself. (I still can’t look at a barred owl without saying “Who cooks for you? Who cooks for you all?” inside my head.)

If you’re out birding and you get stuck, use your phone to record weird bird noises and try to identify them later using your field guide or Xeno Canto, an online library of global birdsong.

And lastly, just stick with it. My “no binoculars” day was enough to convince me that knowing birdsong really does up your birding game, even if it is a struggle.

What a wonderful article! Thanks for the humor.

When I was growing up, almost nobody in my extended family owned a pair of bins. I think just one of my uncles, who quickly learned to “forget” to bring them to family gatherings at our grandparents’ farm. But my family was highly attuned to the world around them, and were skilled observers. We kids were taught birds by their sounds and how they flew, how they stood, where they were. Some birds we could get a good look at; others were only pictures in a well-used Audubon manual. But we knew them. I bought my first pair of bins as a young single mother, and used them to take my kids birding. We learned wild plants in a similar fashion: by looking at which plants grew in what conditions. Type of soil, how much water or lack of it, shade, sun. We learned communities of plants that tended to be found together. And it was a short step to understanding that the communities attracted certain birds. Wow. I ended up studying environmental science and then working in the field. And teaching my grandchildren about using the clues that are inherent in the world, the way my grandparents taught me.

THANKS FOR THIS INTERESTING BLOG