Warning: This story contains graphic photographs of dead sea turtles.

The air is hot, thick and humid as I stroll through the market in a small island town in Melanesia. Women sit behind tables laden with neat rows of banana, peanut, watermelon, and smoked fish. Children play at their feet. Shoppers haggle.

It’s a peaceful scene, until I turn the corner. Two sea turtles lay on the grass, motionless in the relentless tropical sun. A price is scrawled in black marker on each of their underbellies; they’ve been discounted as the day wears on.

I lean in to inspect the merchandise. Only then do I see the turtles’ throats rise and fall as they gasp for air. They are still alive.

Legal Loopholes Fuel Illicit Trade

Uncomfortable as it is for a westerner like me, this sight is not uncommon in Papua New Guinea and the Solomon Islands, where sea turtles are an important part of the local culture and are regularly consumed as food.

“Under law, local people are allowed to catch turtles for themselves and for their families to eat,” says Simon Vuto, a scientist with The Nature Conservancy (TNC) and local Solomon Islander. “But it’s illegal to sell turtles, take their eggs, or to kill a female that is nesting on the beach.”

Those restrictions are put in place to protect sea turtles from overharvesting, as most species are experiencing catastrophic population declines in recent decades. Hawksbill turtles are particularly vulnerable, as their shell can fetch hundreds of dollars on the illegal wildlife market.

And yet, the illegal trade continues. Local carvers purchase hawksbill shell to make their jewelry, and smugglers ship or carry shell out of the country to buyers in Southeast Asia and China. Foreign visitors can even buy turtle shell hair combs and bracelets in the international airports in Port Moresby and Honiara.

The ongoing illegal trade is especially concerning in the Solomon Islands, which has the largest hawksbill sea turtle rookery in the entire South Pacific. After decades of work by TNC and local communities, the Arnavons rookery was recently declared the first ever marine protected area in the country.

“We’ve seen a lot of recovery in the Arnavons, but that’s likely the exception,” says Richard Hamilton, director of TNC’s Melanesia program. Most of the turtles that nest there spend their lives in the protected waters of eastern Australia, migrating to the Arnavons only to lay eggs. Once they arrive, they’re in great danger if they leave the boundaries of the protected area. “It’s an island of protection in a sea of death,” says Hamilton.

The problem, as it so often does, comes down to enforcement.

“The government has a good policy in place to protect turtles, but they don’t implement or enforce or monitor it,” says Vuto. As a result, no data exists on how many turtles are harvested for subsistence, where they are caught, or how many end up sold to illegal wildlife traffickers. And until 2018, very few wildlife trackers have ever been prosecuted for illegally selling sea turtles.

“We need that data to help make the point to the government that they need to do more to enforce their existing policy,” says Hamilton.

The Turtle Detectives

To gather this data, Vuto and Hamilton needed a network of in-country informants. So they assembled 10 conservation monitors from across the Solomon Islands and trained them to collect the necessary data.

Their mission was simple: find and document every dead turtle in their community. Armed with clipboards and cameras, the monitors convinced local fishermen to alert them each time they harvested a sea turtle.

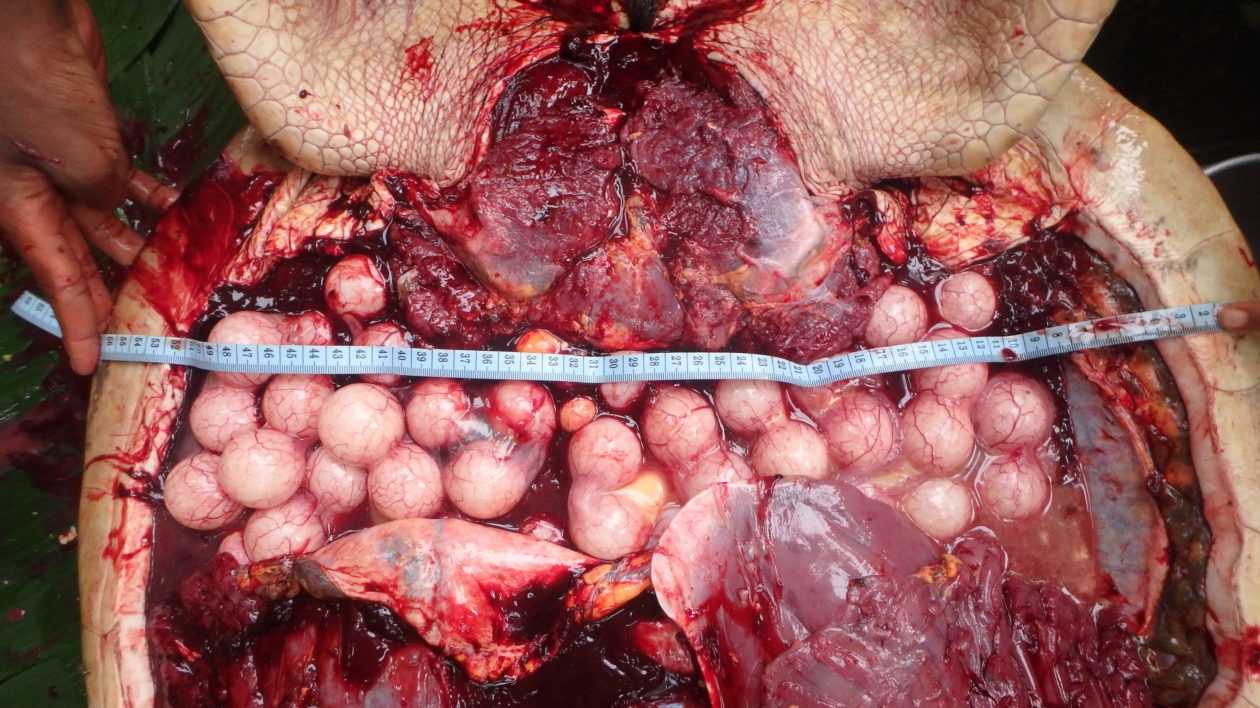

Then the set to work gathering a slew of data. They took detailed measurements of each turtle’s body and asked where, when and how the turtle was caught. Monitors also worked with TNC staff and local fishers to develop detailed maps with local reef names, enabling fishermen to pinpoint the exact reef where the harvest took place.

The monitors also took photographs of each turtle, which are used to confirm its species. One of those photos was a close-up of the left side of each turtle’s face. The pattern of scales on each face is unique, much like the stripes of a zebra or spots of a jaguar. Scientists at the World Wildlife Fund are creating a software program that will help conservationists identify and track individual turtles from facial marks alone, rather than clipped-on flipper tags.

The monitors also took a DNA sample, which scientists will use to determine if certain populations of sea turtles are being harvested more intensively than others.

Finally, they asked the fishermen if the turtle would be eaten — perhaps for a family gathering, Christmas celebration, or church day — or if it would be sold illegally, and at what price. Vuto explains that fishermen in the provinces were willing to admit any plans to sell the turtle because there is no enforcement of the existing laws banning that trade.

Each monitor worked for 18 months, prowling markets, interviewing fishermen, and photographing carcass after carcass.

When the initial data came in, the results were staggering. “We documented by sight 1,112 turtles harvested for subsistence and trade purposes,” says Vuto. He wasn’t surprised. Those numbers line up well with his observations from living and working in the Solomon Islands his entire life.

Vuto says that a majority of the turtles were harvested for subsistence purposes, served at funerals, grave blessings, weddings, and birthday parties. And most of the captured turtles were juvenile green and hawksbills, likely because fishermen rarely see adult turtles in recent years.

While a full analysis of the data is forthcoming, these preliminary numbers are concerning. Monitors relied on fishermen to report captured turtles, so the tally of 1,112 turtles is less than the actual harvest total. (An additional 411 turtles were killed, but the monitors weren’t alerted in time to collect data.)

We documented 1,112 turtles harvested for subsistence and trade purposes.

Simon Vuto

And TNC’s investigation only covered a small part of the country. “There are about 4,000 coastal communities in the Solomons, and we only got data from 10 of them,” says Hamilton. “When you do the math… that’s a lot of turtles.”

Vuto and his partner Chris Brown at Griffith University will use this information to identify hotspots of turtle harvest and compare them to important nesting beaches. They will also overlay turtle harvest numbers with human population data to estimate the scale of the turtle harvest across the country.

Hopefully, the results will convince the national government that they need to step up enforcement and prosecute wildlife traffickers.

“In our interviews with the hunters, they said that in the past that it was easy to hunt turtles, but now it’s a big challenge,” says Vuto. “We are driving the population down, and we need to work together if we want turtles to have a future.”

The researchers would like to acknowledge the Minimising the Illegal Killing of Elephants and other Endangered Species (MIKES) project for providing financial support for this work. The CITES MIKES project is an initiative of the ACP Secretariat funded by the European Union.

Here on Gizo island now. Just saw a turtle brought in by a fisherman. I flew a long way to come here and dive with the turtles. Sick.

With human overpopulation. Over fishing. Nasty dumping of chemicals warming our waters. The sea turtles and other wildlife will be extinct in the next few years. I’m disgusted

Impressive article drawing attention to serious issue of turtle killing in some parts of the world. We must minimize, if not stopping it totally, their ruthless killing.

Hi Justine,

Thank you for the update on subsistence harvest and illegal trade of sea turtles in Solomon Islands. I suspect the harvest may be more than 1,112 turtles harvested per year. I also did my research on “capture and consumption of sea turtle in Manning strait” and I obtained similar data. More than 70% of the population consume turtle meat in Solomon Islands. I have witness on few occasions, hawksbill turtle meat been sold at central market in Honiara.

Looking forward to hear the outcome on the survey on illegal harvest and trade.

Thank You

Rishi

I’m interested to join the fight to protect the endangered species. I’m from one of the province in Solomon Islands called Makira.