Already, more than half of humanity lives in cities, and there will be almost 2 billion additional urban dwellers by 2030. Forecasts are that humanity may develop an additional area of 120 million hectares. That’s an area the size of the state of Texas urbanized, a massive transformation of the Earth.

What’s a conservationist to do? In the face of this massive urban growth, how can we make the best use of our conservation investments to help protect plants and animals that are endemic to different regions around the world?

That question is exactly what The Nature Conservancy and its partners at Yale University and Texas A & M set out to answer in our recent paper, “Conservation priorities to protect vertebrate endemics from global urban expansion.”

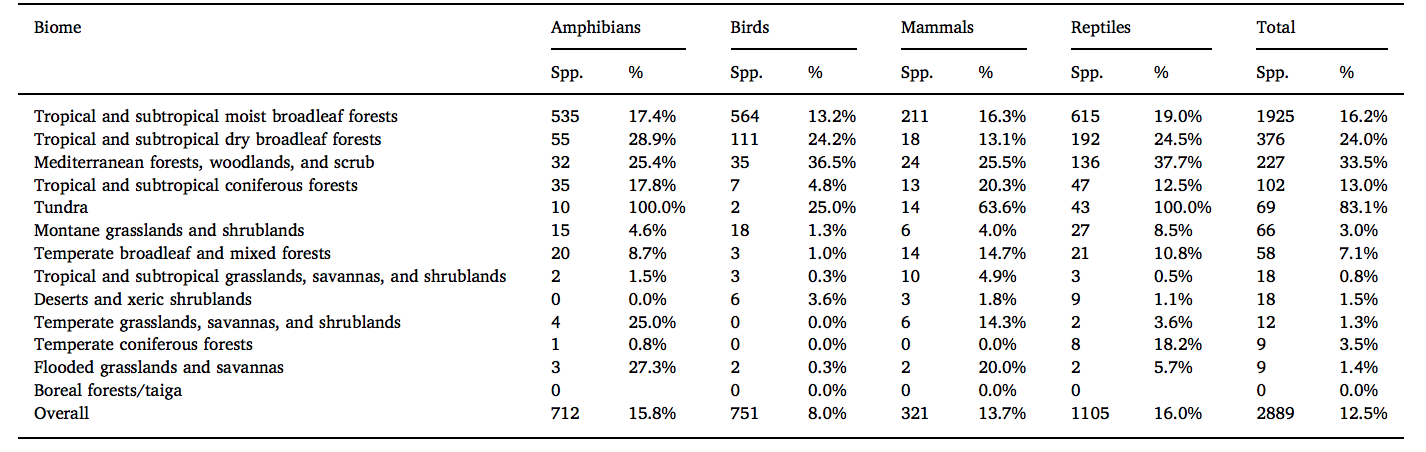

Published in the journal Biological Conservation, we combined global forecasts of urban expansion, information on terrestrial vertebrate endemism in specific ecoregions, and data on current land cover and protected areas to define conservation priorities in those regions. We focused on vertebrates (animals like mammals, birds, and reptiles with a backbone) since there is much better information about the range and conservation status for these groups than for other groups like insects.

We focused on ecoregional endemics since these species exist in one small area on Earth, have small ranges and are the species most at risk of going extinct due to habitat loss. We found that there is both good and bad news.

The bad news is that the potential impact of urban growth on endemic species will be greater than we thought – 13 percent of all endemics will be in ecoregions where there will be significant loss of natural habitat due to urban growth, a far larger impact than the mere area of cities would suggest.

This disproportionate impact occurs because cities are on coasts and islands and river floodplains, places of above average importance for biodiversity and endemism. This large impact of urban growth means that conservationists must consider urban growth and plan to minimize its effects if we want to protect the diversity of life on Earth.

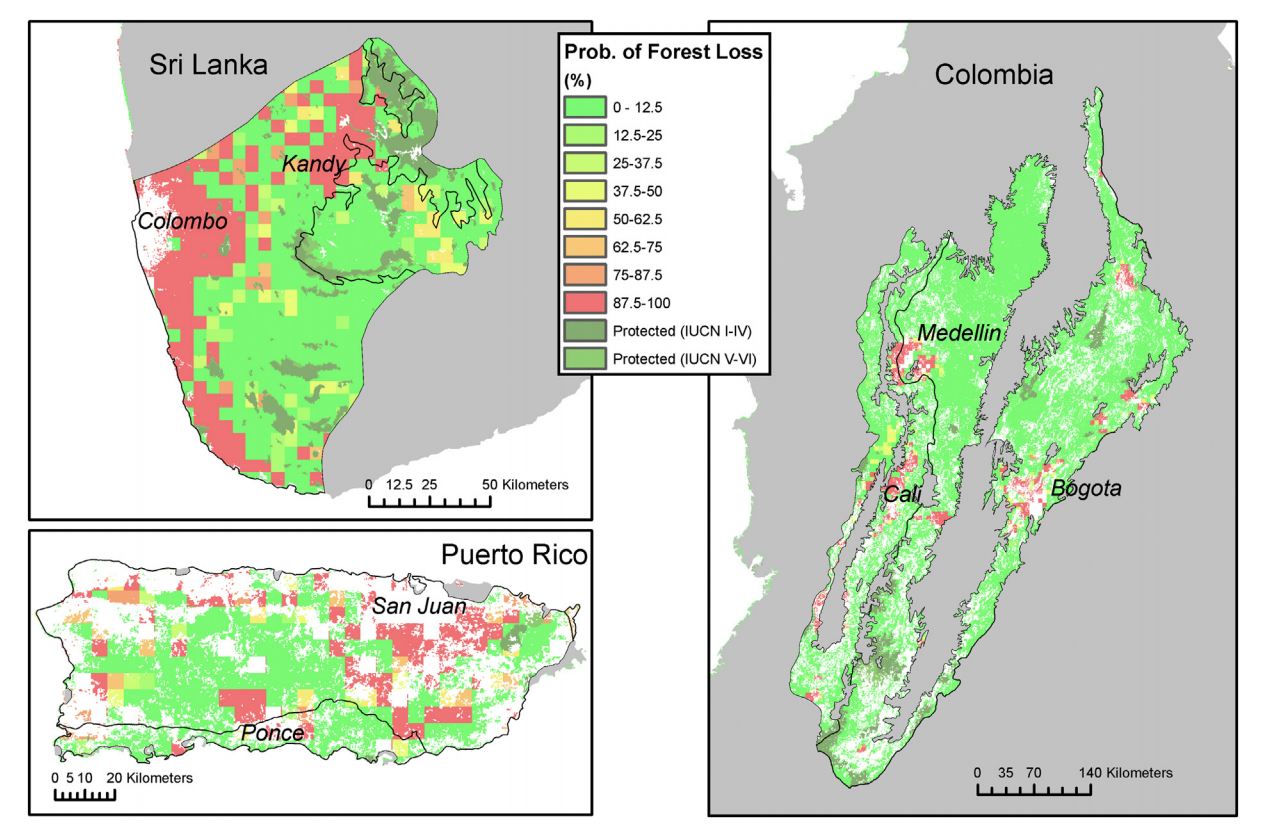

The good news is that the problem is highly spatially concentrated, which in some ways makes the task of urban conservationists easier, since we can focus our efforts on just a few places because 78 percent of all endemics occur in just 30 ecoregions (4 percent of all the ecoregions on Earth). These 30 priority ecoregions for conservation are places where urban growth is forecast to occur on top of natural habitat that is currently unprotected, as opposed to agricultural lands or other already converted land uses.

These priorities are also places with spectacular biodiversity and endemism. It is this combination of things that make places like Sri Lanka’s lowland forest, where rapid urban growth is spreading out of Colombo, globally important priorities for urban biodiversity conservation. Natural habitat protection of 4.1-8.0 million ha, less than 7 percent of the expected total new urban area by 2030, would protect 4 out of every 5 endemics at risk from urbanization.

Such land protection could still allow plenty of room for urban expansion, since most ecoregions have enough space for urban expansion on existing land uses. This incorporation of biodiversity and ecosystem service information into our planning for the expansion of the world’s cities will be key if we want to maintain biodiversity in this century of rapid urban growth. Conservationists and urban planners have the information and the tools to create these wise plans.

What is needed now is the political will and financial resources to plan for and create adequate protected-area networks in these priority ecoregions.

People will NEVER agree to stop having children, so there is nothing we can do. Procreation of the human race will cause the death of this lovely planet.