Protected areas — they’re the foundation of modern conservation efforts, the most common tool used by every nation to safeguard biodiversity against human influence. But what if they don’t actually work?

New research finds that one-third of all global protected land is under intense human pressure, questioning the effectiveness of these areas for biodiversity conservation.

Mapping Humanity’s Footprints on the Land

Since the 1992 Earth Summit in Rio de Janeiro, the extent of protected areas has roughly doubled in size, to 14.7 percent of the world’s land area. Lauded as a sign of hope for biodiversity in an otherwise dark world, this expansion is tied to the Convention for Biological Diversity, an international treaty in which signatory countries committed to include at least 17 percent of their land in effectively managed and ecologically representative protected areas by 2020.

“The conservation community keeps celebrating this massive protected area estate, but no one is asking the obvious question,” says James Watson

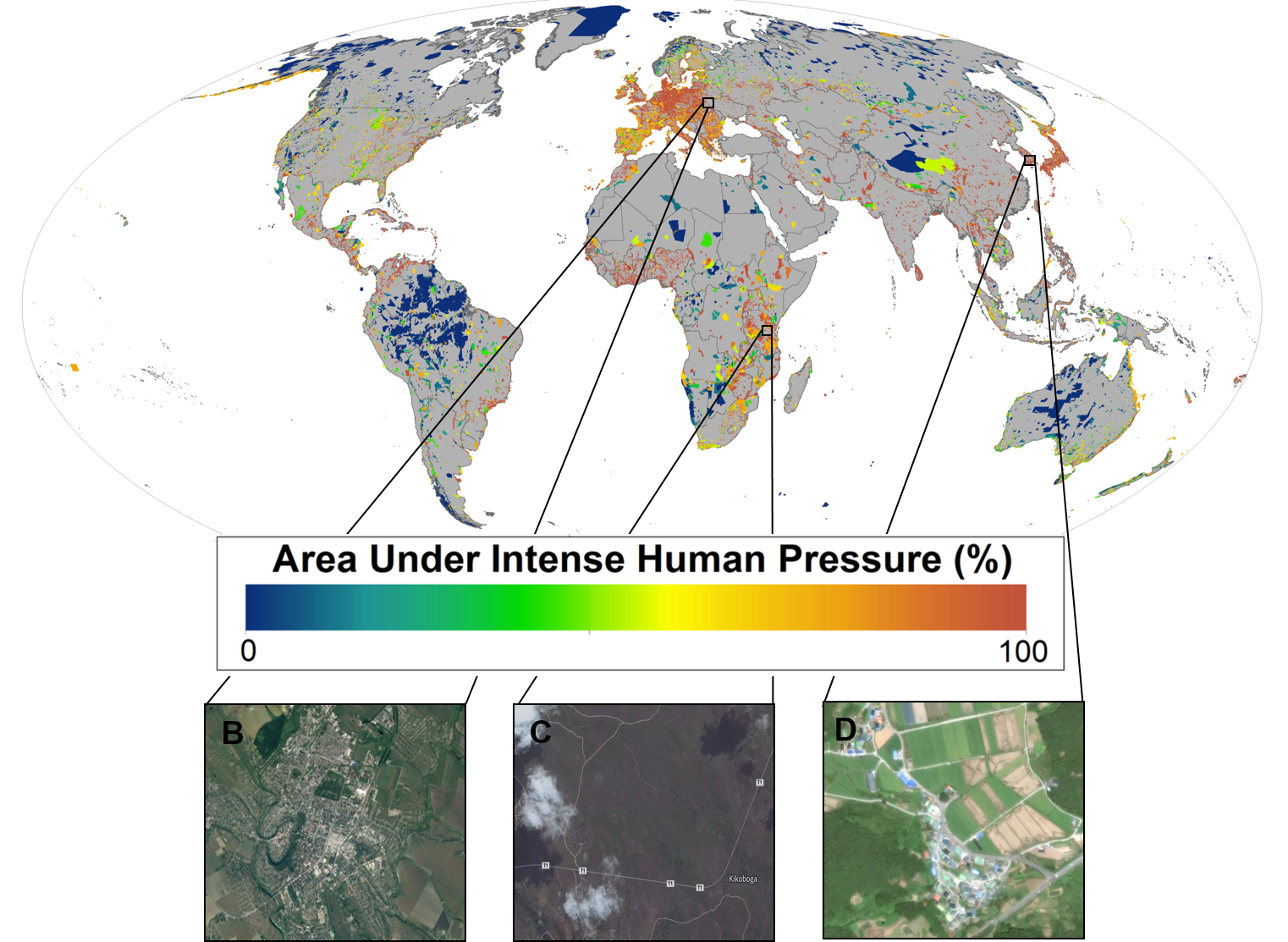

To answer that question, Watson and his colleagues in Canada and Australia mapped human pressure within 8,950 of the world’s protected areas. Their dataset combines eight signatures of human presence — built environments, agriculture, pasturelands, population density, nighttime lights, roads, railways, and navigable waterways — to estimate the amount of human pressure on the landscape, and by inference a loss of biodiversity.

Their results show that more than one-third of global protected lands are under intense human pressure. “That’s about 6 million square kilometers of land that’s being harmed” says Watson, “or twice the size of Alaska.” Furthermore, only 42 percent of protected land is free from measurable human pressures, while an estimated 57 percent of protected areas contain only land under intense pressure.

The team’s results also show that protected area effectiveness doesn’t improve with a nation’s economic status. “Nations like Australia and the United States, who should be setting the standard for the global community, are the ones who are doing pretty badly,” says Watson.

The researchers note that their human footprint dataset does not directly measure the impact on biodiversity, and doesn’t take into account all measures of human pressure, including climate change. Yet Watson says that their result is an extremely conservative estimate, because they are only looking at significant human pressure.

Additionally, the study only took into account 8,950 of the world’s 202,000 protected areas. “So about 95 percent of protected areas are too small for us to even measure if they have human pressures inside of them,” says Watson, “which means that they almost certainly are under pressure.”

A Course Correction for Conservation

To date, 111 nations that have already achieved Aichi Target 11, protecting 17 percent of their terrestrial area. But 74 of those nations would no longer meet their target if we exclude lands already under significant human pressure. Meanwhile, protection of certain biomes, like mangroves or temperate forests, would drop more than 70 percent.

“The text in the CBD says protected areas must be effectively managed for conservation, but we need to actually uphold that definition,” says Watson.

Another potential solution is to direct limited conservation dollars to better management for existing protected areas, instead of racing to establish new ones. “The evidence is mounting for increased management trumping expansion as the best investment in conservation for many countries,” says Hugh Possingham, chief scientist for The Nature Conservancy.

He cites recent research from the Great Barrier Reef which demonstrated that expanding an existing protected area can actually have negative conservation outcomes, because it spreads enforcement out over a larger area, thereby increasing the likelihood of poaching or other illegal activity.

“Environmental NGOs, like The Nature Conservancy, are the ones that can lead the way by investing in protected areas and endowing their management costs,” says Possingham.

Thanks for sharing your concern and it is true that increasing population threatens wildlife safety and it should be answered with innovative projects to make the wild life threat free. Hope things change quicker.

Most of the water bodies in India and many other part of South-Asia need attention for biological conservation . Over populated river sides and it’s economic impact can be topic for further studies on how to free them from over congession .

Lets all support innovative projects that protect vulnerable wildlife from extinction, while restoring balance to threatened ecosystems and communities.

http://chs.uonbi.ac.ke/