As we head into spring in the northern hemisphere, our days grow longer. Our minds may naturally turn away from thoughts of snow, ice, frozen wastelands, and Arctic blizzards.

The Great Thaw

While we yearn for spring and warmer days, the fact is that we are never far from the deepest cold—permafrost currently underlies about 25% of the land in the northern hemisphere. Occurring primarily in the northern latitudes, permafrost includes lands where the soil has been permanently frozen for two or more consecutive years. Sometimes, it just doesn’t thaw out, and remains frozen for millennia.

I had my first exposure to permafrost in 2001, while I was spending a summer on a research project investigating climate change in the Scandinavian subarctic in Abisko, Sweden. The project involved a set of experimentally-manipulated plots that simulated a future climate scenario: in comparison with controls, we heated the ground and air five degrees above ambient temperatures, and doubled the concentration of carbon dioxide in the atmosphere.

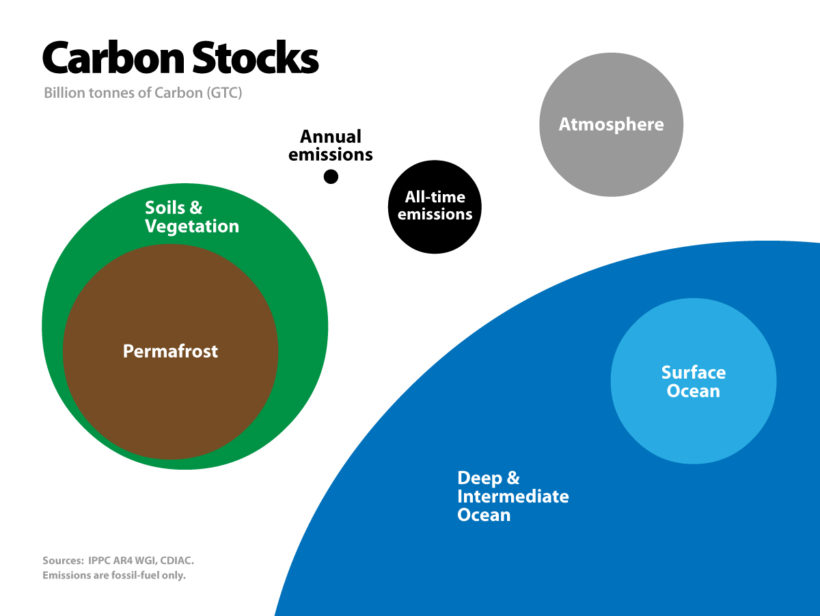

When heated above freezing in the summertime, permafrost can melt and become seasonally-unfrozen soil. Because permafrost stores a great deal of carbon, its melting can unleash a cascade of biogeochemical changes with potentially huge consequences for our atmosphere and climate, ecosystems, and built infrastructure.

Over the course of my summer in Sweden, I made delicate measurements of photosynthesis and sampled plant tissues to test for physiological differences between the plants growing under the hotter, CO2-enriched conditions vs. the controls. The experiment continued for several years, allowing researchers to investigate the longer-term impacts of climate change on plants, soils, and the soil microbial community within this system. But I saw some differences between the heated and unheated plots even after one year of treatment. In August, saucer-sized mushrooms started popping up in the heated plots. One day, as I leaned over to check a heating cable threaded through the soil, a frog leapt from its hiding place and nearly gave me a heart attack. The fleet-of-foot appeared to be wasting no time in exploring and colonizing new, warmer environments, be they natural or experimentally-created by researchers!

With global climate change, the northern latitudes are warming on a large scale, and permafrost soils have begun to thaw at an unprecedented rate. As the permafrost melts, we are beginning to understand one of its ecologically important roles—the fact that it has served as deep cold storage for an ancient gene pool, preserving seeds from over 30,000 years ago—an era when the planet was a warmer place. Cryopreservation—the storage of biological materials at sub-zero temperatures—has occurred naturally in these systems, and the frozen seeds hang in suspended animation, like living chocolate nibs in a bowl of mint chip ice cream, awaiting the great thaw.

Join the Discussion