The last time fish could migrate unimpeded on Rhode Island’s Pawcatuck River, the United States was not yet a nation. George Washington was a surveyor, not a general or a president.

That’s about to change, as American shad, river herring, sea-run brook trout and other species will soon be able to migrate and access the entire river for the first time in centuries. Here’s how this river restoration success came to be.

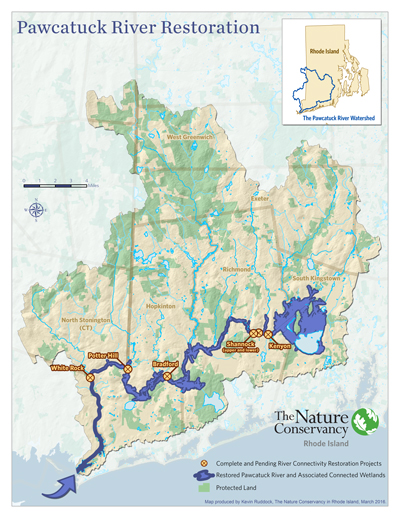

The Pawcatuck River runs east to west in southern Rhode Island for approximately 34 miles. It’s a beautiful, scenic river that has an interesting human history. In the 1760s, three dams were installed for industrial use, and several others would soon follow. By the 1880s, a textile plant dumped dye directly into the river, coloring its waters different hues. Those factories are now gone, but the dams have remained.

Rhode Island began protecting land along the Pawcatuck River watershed in the 1930s; The Nature Conservancy joined the land protection effort in 1972. The river is recognized as one of the healthiest systems in the state, but the river remained poorly connected for migratory fish.

“All of Rhode Island is a watershed,” says Scott Comings, associate state director for the Conservancy’s Rhode Island program. “All rivers are connected to the ocean, but there’s a tremendous number of obstructions in these rivers.”

was perhaps best appreciated from the air. Photo © Ayla Fox

The Wood-Pawcatuck Watershed Association pioneered the effort to reconnect the river beginning in 2010, completing three fish passage projects on the upper Pawcatuck with funding from NOAA and other partners.

In 2013, the Conservancy worked with the Army Corps of Engineers and the U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service Fish Passage Engineering Group to investigate three additional dams on the lower Pawcatuck River. While the lower dams had fish passage facilities, few if any fish were actually passing them.

In 2013, the Conservancy worked with the Army Corps of Engineers and the U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service Fish Passage Engineering Group to investigate three additional dams on the lower Pawcatuck River. While the lower dams had fish passage facilities, few if any fish were actually passing them.

“This is a classic example of what The Nature Conservancy does so well,” says Comings. “We found out who we needed to work with, and then how best to engage them.”

The Nature Conservancy signed an agreement with the U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service, and began work on restoration at all three dams on the lower Pawcatuck. The Conservancy put a management team together, hired engineers and contractors and secured necessary permits.

In 2015, the first dam – known as White Rock – was removed. The Potter Hill dam was determined to not be feasible for removal, but a half-day’s work with a long-armed excavator unblocked the entrance to the existing fish ladder. The last dam, Bradford, was just replaced with a rock ramp fishway.

and weirs. Here, excavators are using a relay barge to plug small leaks in a weir. Photo © Ayla Fox

This last dam removal presented a challenge: the dam created wetlands that were protected with funding from the North American Wetland Conservation Act. Those wetlands needed to remain to meet grant requirements. As such, the dam was removed but a rock ramp fishway was installed, allowing migratory fish to easily move up river. The rocks continue to hold back the river, preserving wetlands and boating opportunities.

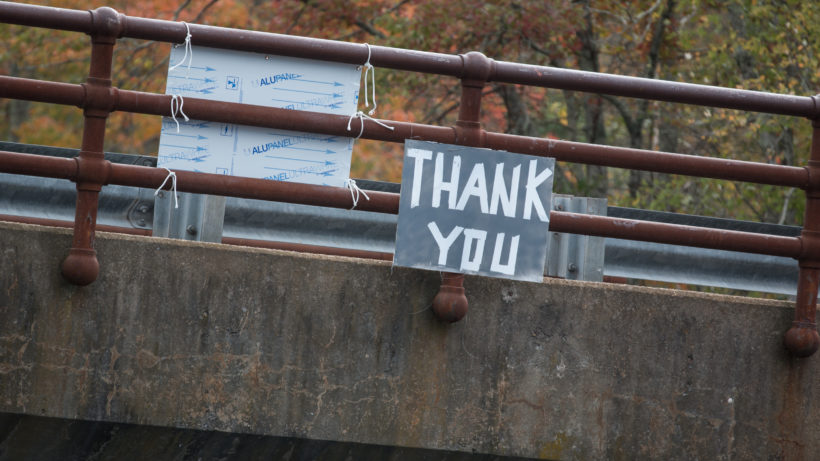

Across North America, many dam removals – even small, non-functioning dams – result in controversy. But that simply wasn’t the case here. “The local community was so excited by the project,” says Comings. “It will improve fishing and boating, and there was pretty much unanimous support for it.”

The Bradford dam removal occurred just downstream of a bridge, and people gathered to watch every day. Some community members hung a “Thank You” banner from the bridge.

“On the day the river was connected, about 50 people gathered on the bridge,” says Comings. “Even though there was not a lot to see in that final step of the project, folks wanted to be there. The project foreman bought pizza to share with the spectators. That was the spirit around this dam removal.”

This final removal opens up nearly all 34 miles of the river to migratory fish. Herring and shad will now be tagged and tracked to see how they’re using the river.

Now the Conservancy is shifting attention in Rhode Island to smaller coastal streams, looking at retrofitting under-performing fish ladders. The support of the Pawcatuck’s restoration can help propel connecting more of the state’s waters.

“This is one of those once-in-a-lifetime projects,” says Comings. “We had the opportunity to connect and restore ecologically important waters, and the project was loved by the community. How often do you have a chance to connect a river for the first time in 250 years? It is a new chapter in the history of the Pawcatuck, and the support for that has been amazing.”

Join the Discussion