During Australia’s first decades as a British colony, oysters were so cheap and plentiful that settlers used them to pave roads. But today the country’s shellfish reefs are gone — overfished to the point of collapse — and scientists have a very limited knowledge of where they once were.

New research from Nature Conservancy scientists draws on the historical record to map the former extent of Australian shellfish reefs and assess just how much we have lost. This new data will feed some of Australia’s first efforts to restore shellfish reefs across the nation.

A Convict Colony Built on Oysters

You can still glimpse traces of Australia’s oyster-filled past, if you know where to look.

A few kilometers west of the famed Sydney Opera House — where non-native oysters sell for AU$24 per half dozen — sits the Old Government House in Parramatta. Dating to 1799, it’s Australia’s oldest surviving public building, built using shells from nearby Aboriginal middens to strengthen the mortar. And just a few kilometers south, you’ll find the affluent Oyster Bay suburb.

Similar remnants of history litter the coast, holdovers from a time when Australian shellfish reefs stretched across an area of equivalent to half of the United States coastline. But the reefs themselves disappeared long ago. “Today our shellfish reefs are very scarce and severely degraded,” says Chris Gillies, marine manager for The Nature Conservancy’s Australia program and lead on the research.

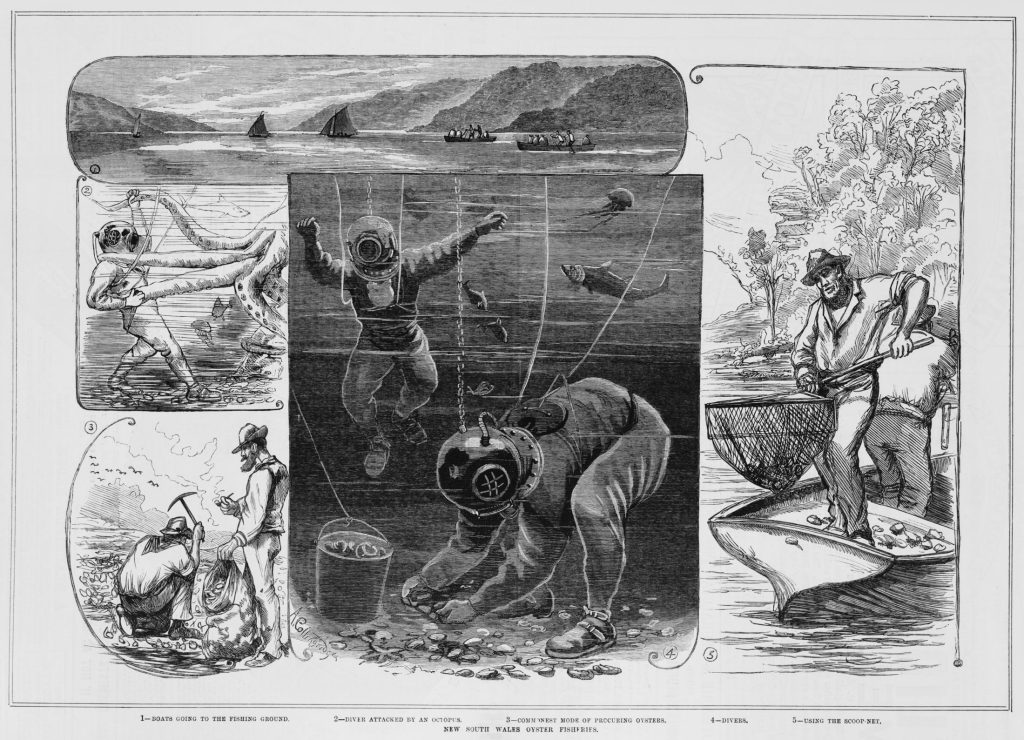

Britain established the first convict settlement in Sydney in 1788, and just a century later oyster fisheries collapsed across the country. “Along with fish, oyster meat was probably the cheapest protein source in the first 50 to 100 years of colonization,” says Gillies. Fishermen harvested oysters using small metal dredges that scraped along the reef, removing adults, juveniles, and the reef bedrock as well.

Colonists also mined the reefs for building material, burning the lime-rich shells to create cement. That further eroded the reefs by removing the substrate that baby oysters need to attach to in order to grow. Farther inland, land-clearing for livestock and agriculture caused erosion, and these sediment-rich waters flowed downstream and smothered shellfish.

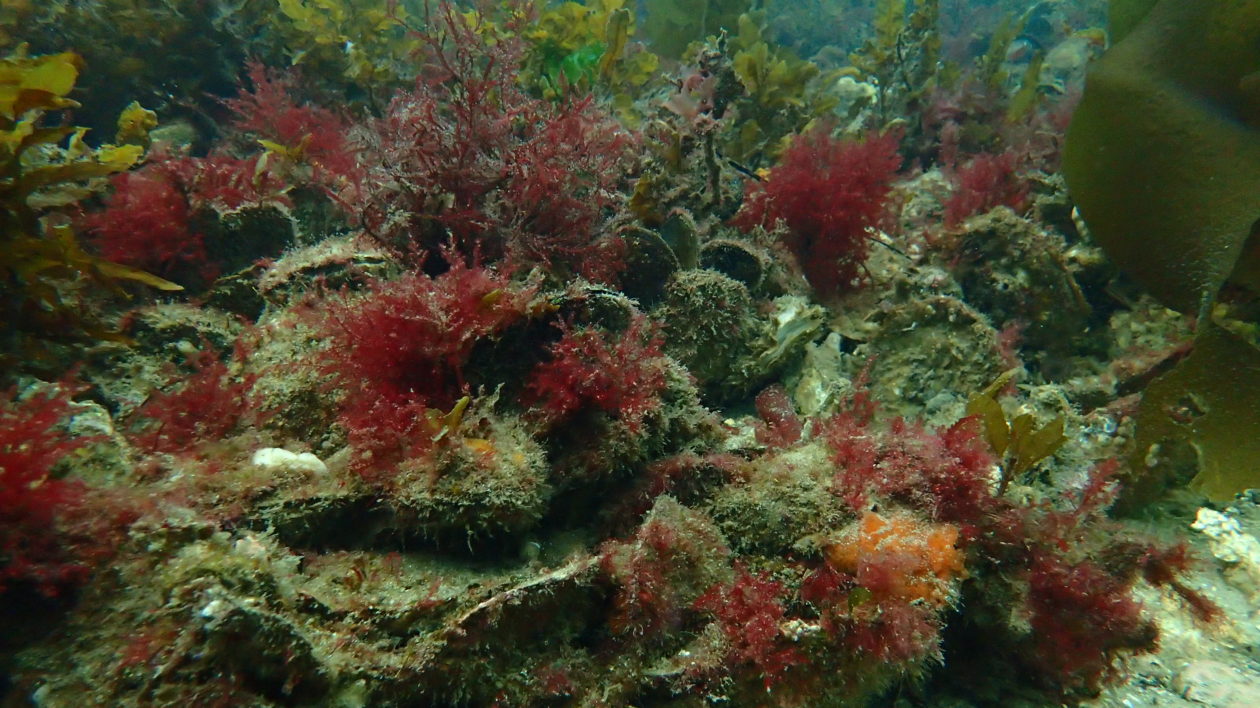

Now, the few reefs that do remain are severely degraded. “Once there would have been more than 100 oysters per square meter, stretching across anywhere from hundreds of meters to several kilometers,” says Gillies. “Now you’ll find only a scattering of small remnant reefs with a lot fewer oysters struggling to survive.”

Dredging History to Map Reefs

Conservationists in the US are successfully restoring oyster reefs in the Gulf of Mexico, experimenting over 20 years to figure out how to efficiently rebuild these ecosystems. But for restoration to be an option, scientists first need to understand where reefs once occurred. And in Australia, even such simple knowledge is often lacking.

“We lost our reefs so long ago that we just don’t have a great sense of where they used to be, or even what they used to look like,” says Gillies.

To answer these questions, Gillies and a team of Australian researchers turned to history, searching through records as far back as the 1770s, when the first European colonists arrived. They sourced data from historical newspaper articles, historical fisheries and aquaculture records, and even accounts from early explorers. (The famed James Cook, only a lieutenant at the time, wrote about the oyster reefs of Botany Bay when he landed there in 1770.)

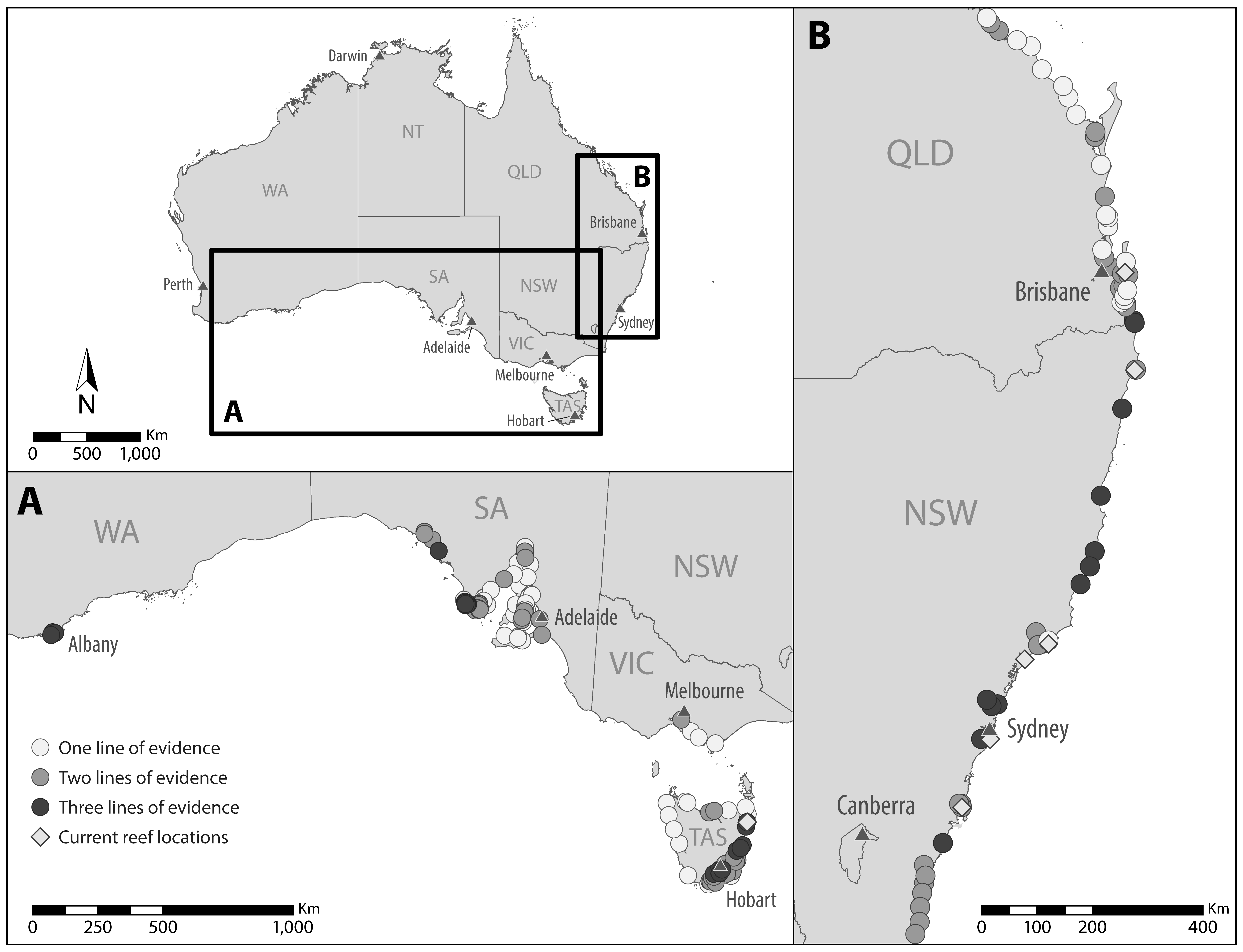

They looked for evidence of sites with commercial shellfish harvesting, which they used as a proxy for the presence of reefs. They also scanned a geographic database for locations with names associated with harvesting, like “Oyster Harbour” or “Limeburner’s Bay,” which suggested that the reefs were a distinctive enough feature that harvesting likely occurred in the vicinity. Finally, they also incorporated archaeological evidence of Aboriginal shellfish middens, some dating back 6,000 years.

Combining all of these data, Gillies and his team were able to map the historical distribution and extent of reefs throughout coastal Australia.

Prior to this research, marine managers and scientists were aware of two reef-building species. Gillies and his team discovered that at least 14 bivalve species once formed reef systems. “Out of those 14 species,” says Gillies, “the two most common have essentially disappeared as an ecosystem — the Sydney rock oyster and Australian flat oyster (also called the angasi oyster).”

The historical data show that these species were once commercially fished at nearly 200 different locations in southern and eastern Australia. Today just seven of those sites have any reef left. Just 1 percent of Australian flat oyster reefs remain — a single site in Tasmania — and 10 percent of rock oyster habitats.

“These reefs are Australia’s most threatened marine ecosystem,” says Gillies, “even more so than the Great Barrier Reef.”

Restoring Reefs Down Under

The fate of Australia’s shellfish reefs is far from unique. Globally, 85 percent of shellfish reefs have either disappeared or been severely degraded. Gillies says that Australia lost a greater proportion of its reefs — about 90 to 95 percent — likely because it had fewer to begin with. “But Australia is special in that, outside of the US, we have the largest and most developed restoration program,” he says.

The Nature Conservancy’s Australia program is leading that restoration effort, together with government and local partners in The Shellfish Reef Restoration Network. The Conservancy has restoration projects underway at three sites, including one in Port Phillip Bay, within sight of downtown Melbourne.

They installed 180 tonnes of limestone rock foundation at two sites, and then seeded those areas with hundreds of thousands of young Australian flat oysters, grown at a nearby hatchery. Eventually, the Conservancy aims to rebuild around 500 hectares of these reefs around the Victorian coastline. The Conservancy also initiated an award-winning shellfish recycling campaign with restaurants and businesses in Geelong, outside of Melbourne, to source used oyster, mussel, abalone and scallop shells for reef-building.

Gillies says that these initial efforts will inform a rapid restoration framework that the Conservancy hopes to use in other temperate ecosystems, including Hong Kong and New Zealand.

In addition to restoration, the Conservancy is also working to guarantee better protection for existing reefs. Despite the catastrophic decline, shellfish reefs are not protected ecological communities under Australian law. “That’s not really the fault of the government,” says Gillies, “because we lost these reefs more than 50 years ago, outside of the living memory of most people.”

It’s hard to protect something if you don’t realize that it’s been almost completely lost, but Gillies’ new research provides the missing data to help restore Australia’s bays and estuaries, one reef at a time.

Join the Discussion