At the turn of the twentieth century, my great-grandparents Robert & Marjorie headed to Foley, Missouri, armed with nothing but a handful of books from the US Department of Agriculture. They learned how to farm on the fly, and there was nothing easy about it. It’s not quite that simple: the farm came from Marjorie’s family (who the town of Foley was named after), so they had some family support. But mostly they had to learn fast!

I think of them when I visit farms from Kenya to California. More than a third of the land on earth produces food, yet many farmers are struggling. Farms and ranches have been intensifying and spreading for a very long time.

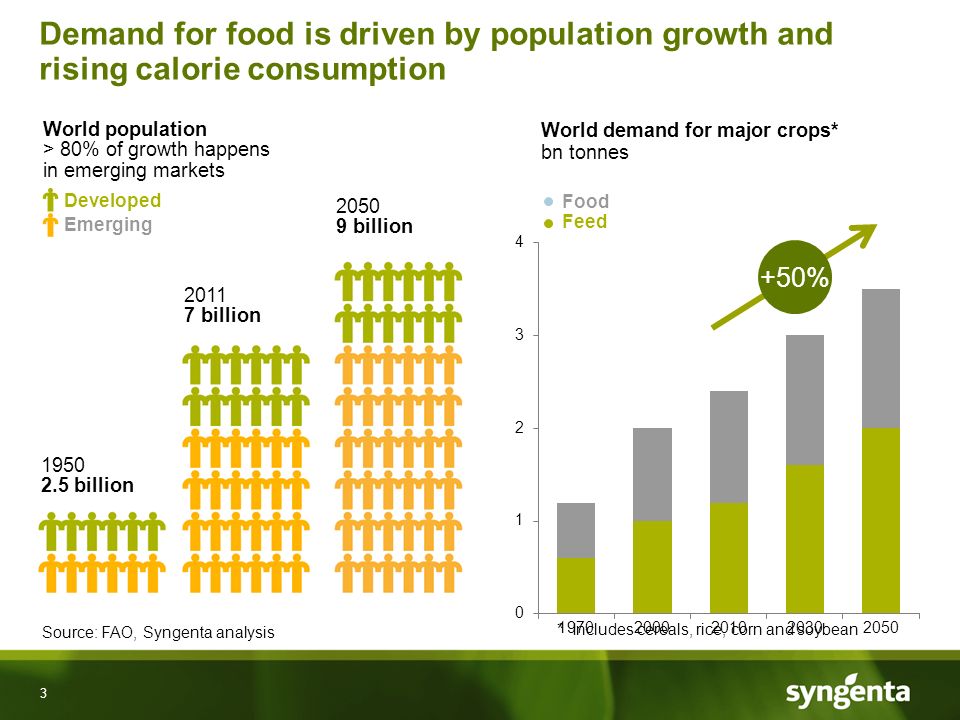

And demand is about to explode. Even though we are already growing more food than we need, people are still starving. To feed the world in 2050, we will need to grow roughly 40% more food. That’s because our population is growing, and diets continue to shift towards more animal products. But there’s a twist that I’m sure my great-grandfather would understand: Farming gets harder every year. Soil is being degraded. Fresh water is in short supply. Climate extremes like drought and flooding have a huge impact. If our current farms can’t meet this coming demand, we’d have to clear a swath of new farmland larger than South America. To be sustainable, we need our farms to survive and keep producing food, while also protecting the environment that we rely on to sustain us all.

If we were talking about Silicon Valley instead of places like California’s Central Valley, we’d be focused on bringing a solution to scale. As a conservation scientist, I want to make sure those solutions protect our environment as well as our food supply. But what if we could do both? What if we could scale sustainable farming?

To find out, I’m working with some partners that might surprise you: Big food companies. That’s because farmers often are more likely to trust advice from their fertilizer dealer or requests from a food buyer than environmentalists. Farmers hear from them frequently, and that gives these companies real influence. We also share some critical goals, like better crop yields and food security, even if we don’t always agree on how to get there. My team (the Center for Sustainability Science) is well suited to tackle this: we look for ways to work with policy makers and business, using science to develop practical solutions to benefit the environment and the economy.

Take Walmart, for example. I’m using science to help America’s largest grocer set the right targets for its sustainability practices and environmental outcomes. I led a team from The Nature Conservancy in conducting a science assessment for Walmart focused identifying the biggest opportunities for improvement in beef production. We’re also working to help Walmart update its criteria for sourcing animal protein. That means giving its buyers guidelines on what to look for, helping Walmart identify promising new strategies to pilot test, and providing similar input to other groups and companies working to improve sustainability. In the end, we hope to meet massive, Walmart-scale demand by using scientific, sustainable practices that work for farmers, consumers, and food companies.

I’m pretty sure the idea of supplying something as big as Walmart would have boggled my great-grandparents’ mind. I never did get to visit my family’s farm. Before I was born, my family started renting out our farm. Eventually, we sold it—it was financially sustainable for 74 years, but not forever. Farmers around the world are facing the same challenges my family did: find a way to adapt to tougher conditions or get out of farming. And with increasing demand for food, we need all the farmers we can get.

Fortunately, I think we have the right mix, right now, to scale sustainability. Science has given us better, smarter ways to grow food. Emerging research on cover crops and other soil health practices, precision agriculture and fertilizer optimization, remote sensing, and the role of habitat in providing pollination and pest control is revealing opportunities to benefit both farmers and nature.

And there are a lot of creative, hard-working farmers out there. They get the concept of sustainability: they need to be good stewards of soil and water to stay in business, and to be able to pass on a healthy and productive farm to their children. To help farmers make a transition to more sustainable practices, food companies have the distribution channels, buying criteria, and other levers that matter. If we all work together, we just may be able to help farms around the world be not only productive but sustainable at scale.

Hopefully the whole idea of more sustainable farms catches on quickly. Have heard of the prairie strips before – sounds really interesting. We need less Big agriculture and factory farms, and more actual crops grown. The enormous amount of land being used to grow feed for livestock, rather than for humans really needs some research done. Time for a change.

Great article, Jon. This passage really caught my attention:

“Fortunately, I think we have the right mix, right now, to scale sustainability. Science has given us better, smarter ways to grow food. Emerging research on cover crops and other soil health practices, precision agriculture and fertilizer optimization, remote sensing, and the role of habitat in providing pollination and pest control is revealing opportunities to benefit both farmers and nature.”

Here in the Midwest, Iowa State has conducted some fascinating research on the use of “prairie strips” in agriculture. Most of this work has been done at Neal Smith NWR in Phase 1 of the project, but recently they have begun Phase 2 and are implementing the work on 45 commercial farms. The prairie strips concept is intriguing precisely for the services it offers—perhaps as an alternative to traditional monoculture cover crops—and the co-benefits it offers including pollination, soil health, carbon storage, etc. More than 30 publications in, it is looking like a win-win for farmers and nature

https://www.nrem.iastate.edu/research/STRIPS/

If Big Food helps you open conversations with food producers, go for it! Farmers I know who worried about leaving the land in shape for their children have now passed on, and their sons are so far in debt for chemicals and big machinery they believe they have to farm more and more acres to make ends meet. Trees and grass buffers are just in the way now that machinery is so big and topsoil is going down to New Orleans again. Is that what you what you mean by scale? Hope the conversation continues!