This is one of those stories where the truth is stranger than fiction. And certainly uglier.

You’ve probably seen a picture of the utterly ridiculous Mola mola before. But this species and its other mola brethren are even stranger than their unforgettable appearance suggests. Slimy and brimming with parasites, they’re shapeshifters that out-gun every vertebrate fish in the ocean and even dupe unwitting scientists.

So read on to learn more about the mysterious Mola mola.

-

It’s named after a millstone

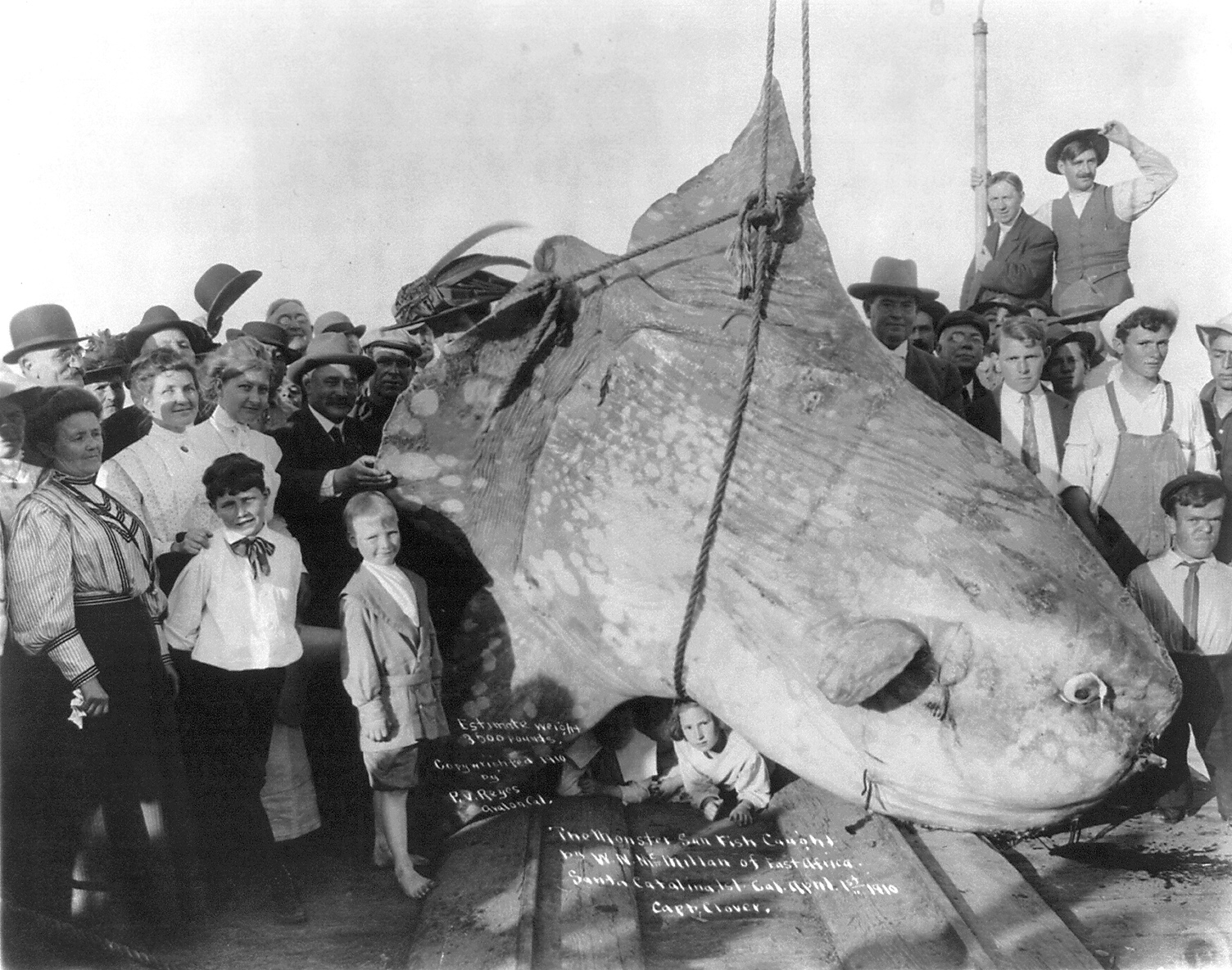

Photo © P.V. Reyes / Flickr Mola mola… it’s so nice we have to say it twice. But not really. This funky double-moniker is actually the species’s scientific name: genus Mola, species mola. “Mola” is latin for millstone, another large, round, grey, rough object. It’s not the most creative name, but it’s apt.

The mola’s English common name — ocean sunfish — is a nod to its habit of basking on the ocean’s surface so seabirds will rip parasites out of its skin. (But more on that later.) In many of Europe’s Romance languages the species is called the “moon fish,” in German it’s the “swimming head,” and in Chinese it’s the wonderful “toppled wheel fish.”

There are actually three known species in the Mola genus, with one just discovered in 2017. Mola mola is the largest and best-known, found pretty much everywhere in warm and temperate waters. Mola ramsayi, the southern ocean sunfish, hangs out below the equator in waters off of Australia, New Zealand, Chile, and South Africa. And the newly discovered Mola tecta, the hoodwinker sunfish, is believed to have a similar southernly range.

-

They’re the largest bony fish in the ocean

Photo © P.V. Reyes / Wikimedia Commons The mola’s odd shape disguises its true claim to fame: it’s the heaviest bony fish in the world. Yes, yes, I know that whale sharks are really big, and they aren’t whales, they’re fish. But they’re not bony fish — the skeletons of sharks and rays are made from cartilage. So when you look at all the other non-elasmobranch fishes out there, molas take the prize for size.

The average Mola mola is roughly 8.2 feet by 5.9 feet, but they can grow as large as 14 feet by 10 feet. The heaviest mola on record is a female caught in 1996 that weighed a whopping 5,071 pounds. For scale, that’s the size of a full-grown white rhinoceros. The mola in the photo above was estimated at measly 3,500 pounds.

Molas are so large that when they collide with boats, the boats sometimes come off as badly as the poor sunfish. In 1998, the cement carrier, MV Goliath pulled into Sydney harbor with a 1,400 kilogram mola impaled on its bow. The fish was so large it dropped the ship’s cruising speed from 14 to 11 knots, and its rough skin stripped the ship’s paint off down to the metal. Yeesh.

-

They’re the most fecund fish (and vertebrate) on earth

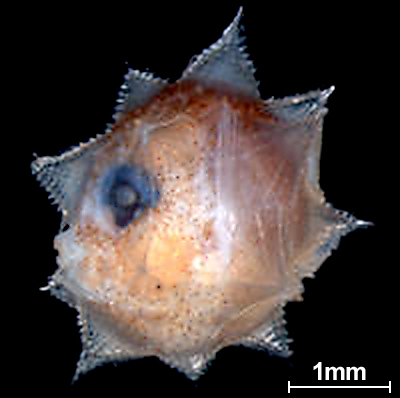

Befitting their size, female molas produce more eggs than any other vertebrate on earth — about 300 million a pop. Yet the baby fish that hatch out of them are the size of a pinhead. And if you thought adult molas were a bit special looking, then take a deep breath. Little mola fry are protected by a star-shaped, transparent covering that looks like someone put an alien head inside of a Christmas ornament. But their appearance isn’t all that surprising once you learn that molas are related to puffer fish.

Photo © G. David Johnson / Wikimedia Commons Those spikes gradually disappear as the young mola grows. By the time they’re adults, their spine is very short in relation to their body, with fewer vertebrae-per-body-size than any other fish. No one actually knows how long mola’s live in the wild, but growth-curve estimates of captive individuals suggested they were at least 20 years old.

So when you’re the equivalent of an underwater flying saucer, how exactly do you swim around? Molas move around flapping using their dorsal and anal fins like a pair of wings, and steering with the lumpy psuedo-tail (called a clavus) on their butt. It’s not efficient, but it works.

-

They have fused, beak-like teeth

Photo © Moosealope / Flickr Have a quick Google for Mola molas and you’ll notice that they all have a meme-worthy look of confused alarm. Every single one. That’s because the mola has a few orthodontic issues: their upper and lower teeth are fused into a parrot-like beak that’s stuck permanently open. It’s perfect for chomping jellies, but it’s not pretty.

Originally, we thought that all mola species spent their days near the surface. That is, until some clever scientists strapped a camera and an accelerometer onto some unwitting molas and waited to see what happened. All of them promptly peaced out and dove to depths of up to 650 feet to snack on jellyfish gonads and siphonophores, a type of invertebrate colonial organism. In addition to jellies and zooplankton, their primary food sources, molas are also known to eat squid, sponges, eel grass, crustaceans, small fishes and deep-water eel larvae.

-

They “hoodwink” scientists looking for new species

Photo © Ilse Reijs and Jan-Noud Hutten / Flickr Meet the newest member of the mola genus: the hoodwinker sunfish. True to its name, this species hoodwinked scientists for decades, hiding in plain sight.

As part of her PhD, New Zealand scientist Marianne Nyegaard sequenced the DNA of more than 150 sunfish. She found Mola mola, Mola ramsayi, Masturus lanceolatus (a sunfish from a different genus) and a fourth mystery species that didn’t match with DNA from any known fish. Cue a big, scientific “What the heck?”

So Nyegaard went on what she describes the four-year treasure hunt to find the mystery mola. She searched pictures of sunfish online, looking for oddities, and asked other scientists to let her know when they found molas so she could collect a DNA sample.

In 2014 another group of scientists hauled up a mola with a weird structure on its butt, and took photos and a DNA sample. Shortly after, four sunfish with the same feature stranded on a New Zealand beach. And the DNA results matched the mystery mola.

The hoodwinker, Mola tecata, looks a bit different than Mola mola and Mola ramsayi: it’s on the smaller side, it’s mouth doesn’t jut out as much and it’s psuedo-tail is mostly smooth, without a lot of lumps and bumps. It’s range is still a bit of a mystery, but so far it’s been located in cold, southern waters off of New Zealand, Tasmania, southern Australia, southern South Africa, and southern Chile.

-

They’re covered in parasites

Photo © LA STaRS / Flickr Back to the parasites. It’s not easy to keep clean when you share a body plan with a dinner plate. (Thanks a lot, evolution). Consequently, sunfish have a bit of a hygiene problem. Scientists have documented more than 50 species of parasites on — and inside — Mola molas. To give you just one disgusting example: the copepod Penella buries its head inside the mola’s flesh and lets a string of eggs trail out behind it.

The fish cope by floating flat near the ocean’s surface and waiting for gulls, albatross, and other seabirds to rip the offending critters out of their flesh. Yummy? (To see this in action, jump to 2:00 in this video clip.) Mola’s sunny surface sojourns also help the fish raise their body temperature after long dives at depth.

I guess whoever came up with the common name kindly chose “sunfish” instead of “symbiotic seabird smorgasboard.”

-

They’re in trouble from wasteful fishing practices

Photo © Tom Bridge / Flickr The IUCN ranks Mola mola as a vulnerable species, and with good reason. Bycatch is a serious problem for molas. They’re pelagic, meaning they swim about in the open ocean, they’re massive, they like to float at the surface…. You can see where this is going.

Molas are frequently captured as bycatch in many fisheries that use long lines, drift gillnets, and midwater trawls. For example, scientists estimate that longline fisheries in South Africa catch about 340,000 Mola molas as bycatch each year. And in the Californian swordfish fishery, researchers found that ocean sunfish made up 29 percent of all bycatch, far outnumbering the target species. Molas are also targeted by commercial fishers in Japan and Taiwan, where they’re a culinary delicacy.

Based on these high bycatch rates and population declines of up to 80 percent in some areas, the IUCN suspects that the global Mola mola population has declined by at least 30 percent over three generations (24 to 30 years). Much less is known about populations of Mola tecata and Mola ramsayi, which are not ranked by the IUCN, but it’s reasonable to assume that they too are suffering from high bycatch rates.

An earlier version of this story, written by Craig Leisher, appeared on Cool Green Science. This updated version draws from his research and writing.

I would have liked an explanation as to how these fish escape predators.

Aww, I wanted the Mola Ramsayi to have cribbed his name from Mola Ram, the antagonist in Indiana Jones and the Temple of Doom. But it got its binomial back in 1883, so no flaming hearts involved in its christening at least from what I’ve deduced.

Just another fun fact on how we humans are ignorent as hell spending billions on flying through space to land a rover on a planet we can’t even live on. I’m sick and tired about hearing how good a job nasa has done . Wake the hell up and try to navigate and understand our life line of this planet,God for bid they might understand more from our oceans than some dead planet in outer space. Oh and the mola mola is beautiful in its own right. Something to take from this is pollute ,over fish ,murder whales and sea turtles .I figure eventually squid and family will populated our already dead oceans,fish and crustaceans will feed on our trash plastic fish for plastic people

WELL WELL WELL

In your thingy it says ,”You’ve probably see a picture of …” This is just before the first paragraph. The “see” should be “seen”.

cool