If you are fascinated with migration, it is a good time to be alive. Sophisticated tracking technologies are revealing migration routes and destinations that have long been inscrutable.

One recent revelation is that small songbirds are bypassing land and making direct flights southbound over the Atlantic Ocean during fall migration in September and October.

It’s an unlikely proposition that a bird that is only the weight of two sheets of paper would opt to fly between one and two thousand miles in a straight shot across open water. It would seem that the better bet would be to take a leisurely route over land where a safety net of habitat awaits below.

Blackpoll warblers, Connecticut warblers, bobolinks and perhaps other species all make this paradoxical choice, setting off across a watery abyss as they make their way to winter destinations in South America.

We know that plenty of birds heading to Central America from the U.S. fly 600 miles across the Gulf of Mexico, but without hard evidence, we’ve been hesitant to believe that a longer open water route to South America was happening.

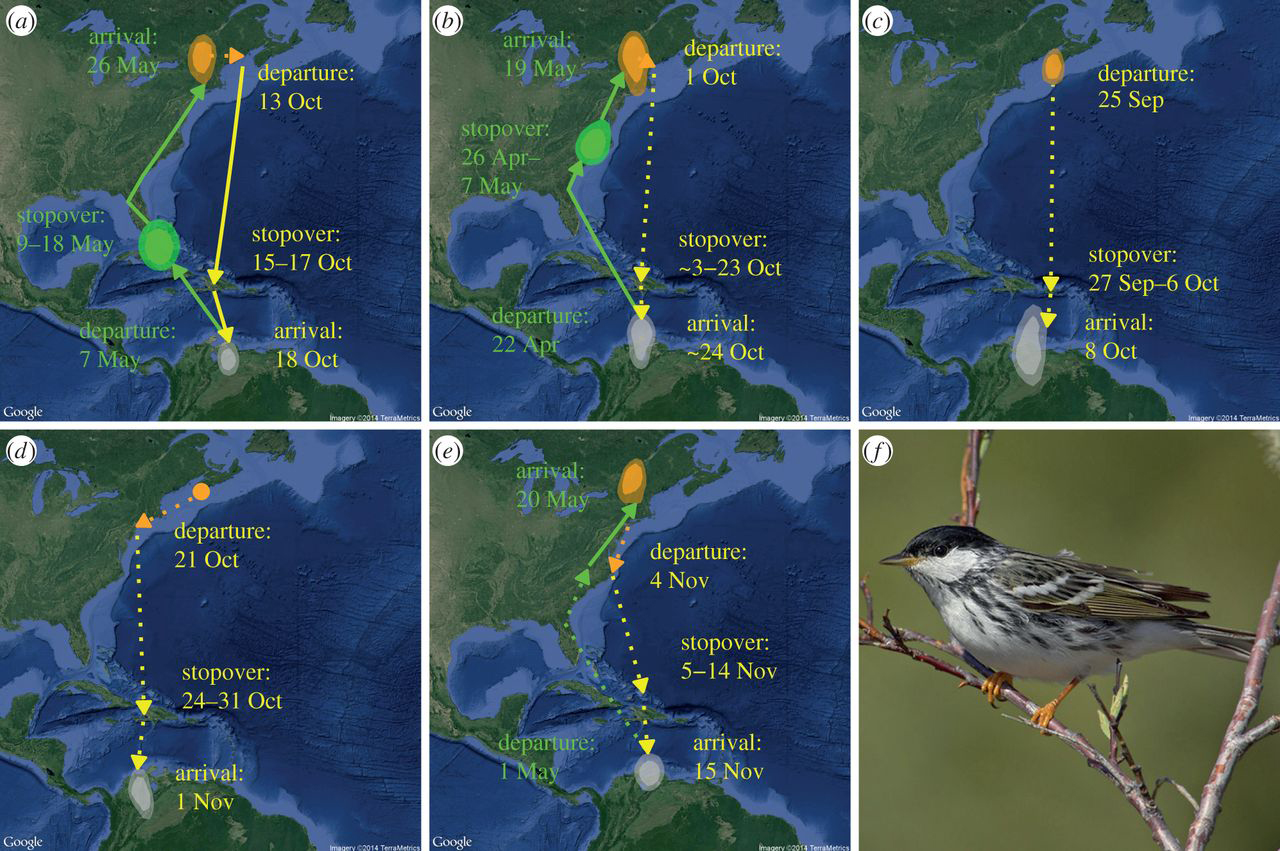

The big news came in 2015 when Bill DeLuca and colleagues confirmed the long-suspected overwater route of blackpoll warblers.

From departure points in New England, the birds made a two to three-day flight to the Caribbean islands of Puerto Rico, Dominican Republic and Haiti. From there, they made a shorter flight to the South American mainland to spend their winters in Venezuela and Colombia.

Prior to this work, earlier researchers pieced together the story of blackpoll migration by using data gathered from radar, bird banding records and sightings in the U.S. and Bermuda. Although they made a strong case, without direct proof some doubt remained. Now we know they got it right.

Bermuda offered migration detectives some critical clues, because any birds appearing there were either lost, swept off course by weather, or intentionally migrating through the airspace above the island.

In the early 1960s, William Drury and J.A. Keith made the case that Bermuda was on the path of a songbird “regular overwater migration route.” They noted that species which wintered in South America were more likely to be seen in Bermuda during fall. If it was just lost birds showing up there, all species would have an equal chance of turning up.

One additional and dramatic bit of circumstantial evidence for the ocean flyway came in 1987 during the confluence of a hurricane and migrating birds over Bermuda. Observers there estimated that 10,000 bobolinks as well as “thousands of Connecticut warblers” took refuge on the island. If you have ever gone looking for a Connecticut warbler, you know that this is truly a staggering observation!

We now know from recent tracking studies of individual birds that Connecticut warblers and bobolinks indeed take an overwater route across Bermudan airspace.

Tracking work by Emily McKinnon and her coauthors that was published this year shows that Connecticut warblers lift off from the east coast and fly for two days before making landfall on Caribbean Islands (Cuba, Haiti and Dominican Republic). They then proceed to South America where they winter in the Amazon River Basin, at the heart of the continent.

Bobolinks also depart southbound over the Atlantic Ocean from the northeast U.S., but this species skips the Caribbean islands and flies 2,000 miles directly to Venezuela and Colombia. From there, they proceed another 2,500 miles to the grasslands of southern Brazil, Paraguay and Argentina to spend the remainder of the winter.

That makes three songbird species proven to use this newly confirmed ocean flyway. Time will tell how many more take this path.

Why do these birds choose the overwater route? To us, it seems a risky proposition to be an animal weighing just a few ounces crossing so much unhospitable space.

But each of these birds, guided by natural selection, is doing its very best to minimize its risks and take the safest journey possible. For certain species, this journey involves crossing the sea.

The birds rely on predictable and favorable winds that buoy them along to their destinations. The winds in the Atlantic create a conduit for migration. Birds use a tailwind to head southbound until they reach tradewinds north of the Caribbean that guide them southwestward to island stopover sites.

The same winds that push birds across the ocean are also used by sailors.

Speaking of seafarers, researchers Drury and Keith even brought observations of Columbus to bear when making their early case for ocean-crossing songbirds. On his first voyage, Columbus happened to be sailing on the tradewinds north of Puerto Rico at the peak of fall migration in early October.

The voyagers observed migrating birds riding the same tradewinds that the three ships were traveling upon. They took note and adjusted their course to follow the “great flocks of birds” toward the Caribbean islands.

We can only imagine the spectacle of migration in 1492, before we took our toll on birds and their habitats.

Since Columbus, we’ve made migration much riskier for birds.

Lights, buildings and habitat loss all stack the odds against a successful migration.

Climate change may also be altering the risks of migration. The predictable winds patterns that bird capitalize on to aid their migration are determined by global climate patterns. As climate changes, winds may also change.

If the winds that shaped the cross-ocean flyway become unpredictable and unfavorable, such changes could be a dramatic yet invisible killer of birds.

Fortunately, predictions of climate change impacts on the migration of North America’s seafaring songbirds are not too dire. Frank La Sorte and his co-authors recently examined projected changes to wind patterns on this ocean flyway and how it might affect the bird populations using it. They concluded that winds may actually become more favorable for migration.

Strong westerly crosswinds that can accompany the passing of a cold front are the bane of a migrating bird on the east coast during fall.

These winds can push migrating birds off course, too far eastward into the ocean. They also make places like Cape May famous. Here, at the end of the New Jersey peninsula, off-track birds accumulate as they cling to a last bit of land before being blown into the abyss.

The strength of the fall westerly winds depends on the temperature differential between the Arctic and regions to the south. A warmer Arctic means less of a temperature difference and weakened winds.

As the Arctic warms, birds are less likely to encounter strong westerly winds that could cause them to delay their departure, use more energy while flying or, if things get bad enough, perish.

Maybe we are off the hook for fall migration, but all migrating birds are facing tougher odds due to climate change and continuing loss of habitat throughout their ranges.

The good news is – thanks to our newfound ability to track small birds over long distances – we can take on the global conservation perspective that is essential to maintaining populations of migratory birds.

For example, we now know that the fate of Connecticut and blackpoll warblers hinges in part on habitat availability and quality in the Caribbean islands.

All the tracked birds stopped at these islands first before heading to South America. Haiti, which is part of this stopover zone, is severely deforested. Lack of habitat makes the journey that much harder for these small birds as they attempt to refuel after flying for two straight days.

The deforestation of Haiti causes big problems for people too. It exacerbates flooding, increases the potential for landslides, and erodes soil fertility.

Migratory bird conservation requires tackling mind-boggling economic, social and political problems in order to get to a better world for the birds (and people!).

But by connecting dots on the many maps that these birds are now giving us, at least we now know where to begin.

When I was young, my brother would tell me that the bird song we heard in our back yard was a bobolink. We had a wooded area full of underbrush and grasses in our back yard. The birds were prevalent and it was a very special thing to hear them call. I would imagine the color and perching bird majically occurring every night but sadly the habitat was gradually lost as our neighbors cleared the brush and overgrowth. The beautiful bobolinks went as well but are still a treasured memory of my childhood. To see the sight of one at Audubon is truly a special treat! Thank you .

Great article, really interesting research!