Life as a hawksbill sea turtle isn’t easy … whether it’s avoiding poachers in the rookery, dodging volcanoes during migration, or surfing through cyclones on the Australian coast.

Despite the dangers, eight of the hawksbill sea turtles tagged by Nature Conservancy scientists last year made it back to their foraging grounds, providing a wealth of new data on their migration routes. Now, a second round of tagged turtles will provide more data, while new protections in the Arnavon Islands provide a major advantage to prosecuting illegal poachers.

Dodging Cyclones and Volcanoes En Route to Australia

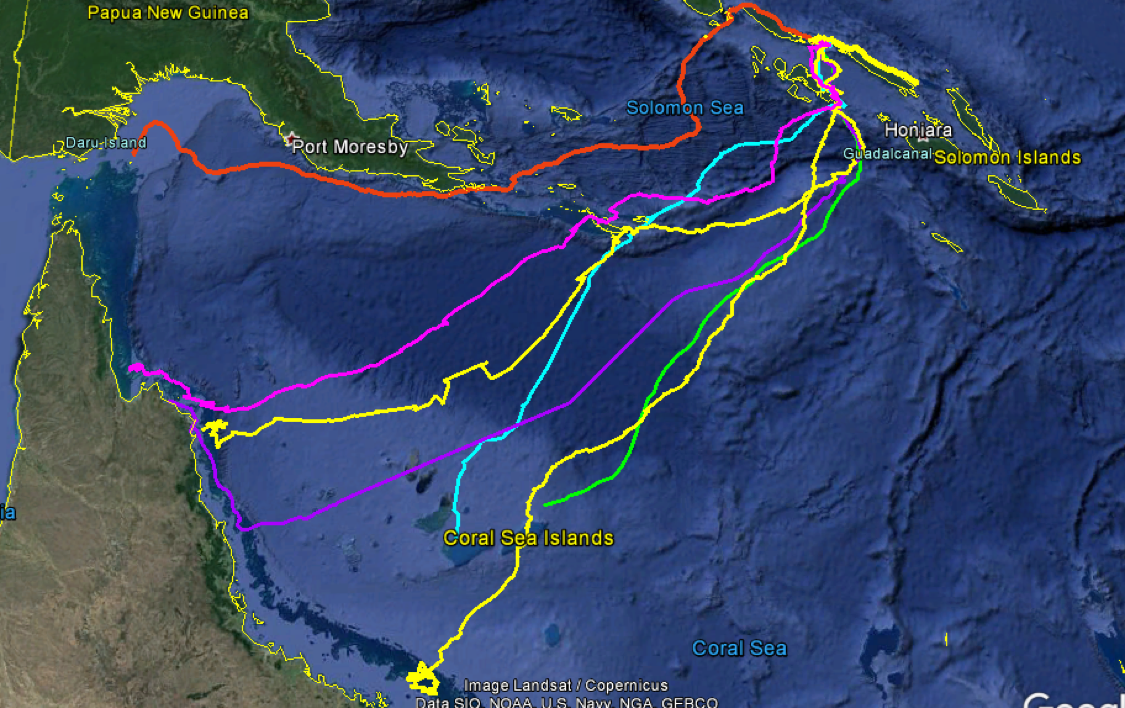

In April 2016, Nature Conservancy scientists traveled to the remote Arnavon Islands and satellite-tagged 10 female hawksbill sea turtles. Two of them never made it out of the Arnavons; they fell victim to illegal poachers just weeks after being tagged. Of the surviving eight, six migrated to Australia’s Great Barrier Reef (GBR) following a direct route across the Coral Sea, with several turtles stopping off briefly in Milne Bay, Papua New Guinea (PNG). As luck would have it, that route took all six of them directly into the path of Kavachi, one of the most active submarine volcanoes in the South Pacific.

Another turtle took a different route, swimming into Milne Bay and then following the PNG coastline past the capital of Port Moresby, before arriving back at its foraging grounds in the Torres Straits. A final turtle stayed close in the Solomon Islands, migrating just 220 kilometers to a reef off of Isabel Island.

“The real big surprise was just how many of them went back to Australia,” says Richard Hamilton, director of the Conservancy’s Melanesia program and lead on the research. “That’s really interesting and suggests that the population recovery we have seen to date is largely driven by the fact that these turtles are moving from protected area to protected area, albeit across 2,000 kilometers of open sea.”

The transmitters Hamilton and his research team attached to the turtles were designed to last about a year. But you never know with remote technology, and Hamilton suspects that the sulfide-rich waters from the volcano stripped the anti-foulant materials from the tags, causing some of them to fail much earlier than expected. Geological challenges aside, the research team still gathered a tremendous amount of data.

And three of the tags are still working — one on the lone turtle that remains in the Solomons, and two on turtles on the GBR — providing data on how the turtles use their foraging grounds. “You can actually work out the specific spots on the reef that they are sleeping in, based off the times,” says Hamilton. Things got particularly interesting when Cyclone Debbie hit the Australian coast in March of 2017, blowing one of the turtles off its regular foraging reef in the Whitsundays for four days.

Perhaps the most significant result has nothing to do with the migration routes, but with the rookery itself. “It seems that, almost by dumb luck, the boundaries of the Arnavons protected area are sufficient,” says Hamilton. “We had no idea where they went in the inter-nesting period, but it turns out that about 95 percent of the time they stay within the boundaries of the Arnavons protected area.”

Hamilton’s data match up with a single previous study, which tagged two Arnavons turtles in 2004. One of those turtles migrated west to Milne Bay, PNG, while the other dropped down to the northern reaches of the GBR. Even then, a mere 10 tagged turtles over two decades is not sufficient data to truly understand their migration routes.

Hamilton needed more data, and more turtles.

Return to the Arnavons

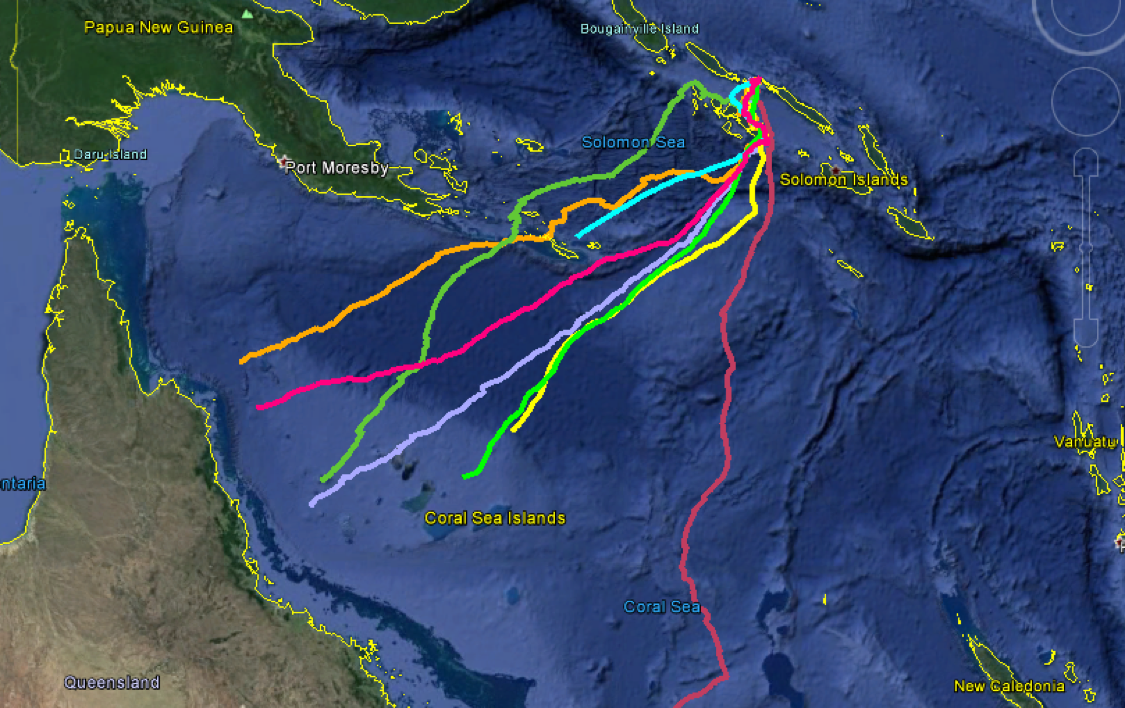

So in May 2017, Hamilton and his colleagues returned to the Arnavons Islands with another 10 satellite tags — this time prepped with a protective layer should any of the turtles decide to spar with the volcano. Capturing 10 nesting turtles was considerably easier this time, as nesting in the Arnavons peaks from May to August and again from December to January. Over four nights Hamilton and the Arnavons conservation rangers caught and tagged an additional 10 turtles.

The goals for the second phase of the study are twofold: to see if these turtles also stay within the bounds of the protected area during the nesting period, and to see if they return to similar foraging grounds.

Hawksbills that nest in the Arnavons don’t return here every year. Data from titanium flipper tags shows that, on average, adult females return to the Arnavons once every five to seven years to lay eggs. Where they reside the rest of the time — and the migration routes they take — are largely unknown. It’s entirely possible that the nesting cohorts from different years migrate back to entirely different foraging grounds, hence the second year of tagging. Ideally, this second set of May turtles will show similar patterns to the first.

Hamilton is also curious about turtles in the second nesting peak in December. Scientists don’t know what drives individual turtles to return when they do, but they do know that, in the Arnavons, they’re highly loyal to that time. “We have titanium flipper tag history for some turtles over four nesting cycles, or 26 years, and they don’t budge,” says Hamilton. “You will never have a turtle that nests in May suddenly change to nest in December.”

In addition to the migration data, this year Hamilton programed the tags to also record how long each of the turtles are out of the water when they are nesting. So far the average haul out lasts about 2 hours, which is a long time where they are vulnerable to poachers or predators. (One of the turtles they saw nesting, but did not tag, had a missing hind flipper — likely the result of an attack from the ever-present saltwater crocodiles).

Now nearly three months after tagging, seven turtles are migrating towards Australia. One of these seven is heading much farther south than any of the others, and is currently in the Coral Sea west of New Caledonia, about 800 km northeast of Brisbane. The eighth turtle has so far migrated to the Milne Bay area, and the ninth recently left the Arnavons and is headed towards Kavachi volcano. A final turtle is still in the Arnavons, where it has nested at least six times.

New Protections To Keep Poachers at Bay

A better understanding of migration routes will help ensure that the Arnavons rookery continues to recover. But the biggest hope for these hawksbills hasn’t come from the tracking data, it’s come from new regulations that will ensure poachers are prosecuted.

In May 2016, two of the tagged hawksbills fell victim to poachers. Watching from Brisbane, Hamilton saw one tracker, and then another, go dark. It was the evening of the ranger shift change, and poachers from a nearby community — neighbors and relatives of some of the Arnavons rangers — snuck ashore and butchered the turtles on the beach.

“We always knew poaching was a threat, but this really drove home the reality that even after all our efforts the Arnavons still weren’t safe,” says Hamilton.

Since then, the rangers have taken significant steps to counter this danger. In the past decade, the majority of nesting has shifted to Sikopo Island, away from the current field station at Kerehikapa. So Hamilton secured funds for a second ranger station on Sikopo. The rangers, who work one-month shifts on the islands, also altered their schedules to make sure that there were no gap days in between shift changes.

But an increased on-site presence wasn’t enough; the islands needed additional legal protection to deter poaching. So Conservancy staff and the Arnavons board of directors used the migration data to secure a long hoped-for protection victory.

In 2010, the Solomon Islands government established a Protected Areas Act to protect unique terrestrial and marine sites. But seven years later, not a single site in the country had been formally protected, mostly due to stringent stipulations for eligibility.

The Conservancy and the Arnavons board of directors spent the past several years working with the communities to nominate the Arnavon Islands for protection under the law. Data from the 2016 turtles helped demonstrate that the boundaries of the existing protected area were sufficient to protect nesting turtles.

In May of this year they finally succeeded, and the renamed Arnavon Community Marine Park became the first location in the entire country to be protected under the act. “This is what we have been dreaming of for the last 20 years,” says John Pita, the Conservancy’s environmental coordinator for Isabel province.

Pita says that the greatest advantage of this change is access to both financial and technical support from the national government — which means true enforcement of the laws protecting the turtles. The new regulations grant the Arnavons rangers legal powers to search, arrest, and confiscate equipment from poachers. Once prosecuted, poachers will now face jail time and fines from 10,000 to 100,000 Solomon Island dollars. The law also provides immunity for the rangers from counter-suits.

“For more than two decades I have seen poachers walk away free because lack of strong laws to punish them, so I have been swallowing my anger and frustrations for that long,” says Pita. “But from the 11th of May, inside of me was lighter than ever before, because I now know offenders will get what they deserve.”

Thank You Justine for the information on poaching and tagging for the Arnavon islands. It means that the rangers have “teeth to bite”. The power the ranger hold will surely decrease the poaching rate which will the good news. Credit goes to Dr. Hamilton for securing fund for Sikopo and re-evaluating how to tackle poaching in the area.