Horseshoe crabs are one of our most beloved invertebrates. Part of their charm is that they are approachable, harmless and capable of creating a spectacle when they emerge from the water to spawn on the shore.

Once on shore, they endear us with their helplessness. They are easily tossed upside down by even the gentlest lapping waves. Most of the time they can’t get right side up again and many eventually perish when stranded out of the water for too long.

Beachgoers among stranded crabs quickly realize that they have the crabs’ lives in their hands. Flip them over, and they live for another day.

Even when upright on beaches, they lumber slowly, ten legs heaving their shell a few inches forward at a time. We rarely get to see horseshoe crabs under water, where they are most comfortable, spry and graceful, gliding swiftly over the bottom.

Horseshoe crabs are perhaps best-known for their role in serving up their eggs to hungry shorebirds, which time migrations stops to coincide with horseshoe crab spawning.

As for the importance of the eggs to creatures under the water, we know very little. It would stand to reason that fish as well as birds might plan their lives around this dependable and abundant resource.

I was prompted to think more about this after hearing a story about eels from Dian Shivers, a volunteer who assists with shorebird conservation work on the Delaware Bay.

In the 1950s, Dian was part of a pack of free-range kids who played on Delaware Bay beaches. During horseshoe crab spawning season, the kids would dig a trench on the beach above the water line, get in the knee-deep water among the spawning crabs and then scoop the slippery eels into the trench with their bare hands.

We presume the eels were there in such easily-caught abundance to feed on horseshoe crab eggs.

Our evidence for this notion comes from another use of horseshoe crabs – as bait for eels. Female crabs full of eggs are hands-down the best bait with which to catch an eel.

An emerging market for eels in the 1990s drove an emerging market for horseshoe crabs as bait. The harvest of horseshoe crabs was unregulated because, until then, there had been no modern use for them. This resulted in a gold rush – the defenseless spawning crabs were plucked off beaches by the thousands.

By the time regulation caught up with the fishermen, the crab population had become seriously reduced.

The eels have fared no better. The Atlantic States Marine Fisheries Commission has concluded that the eel population is “at or near historically low levels.”

Demand for eels is driven by overseas markets (not to mention the global consumption of Unagi at sushi restaurants) that turned to American eels after stocks in Asia and Europe became depleted.

A similar unregulated gold rush ensued, also in the 1990s, when fisherman scooped out millions of young “glass eels” from rivers. The young eels arrive in spring from their birthplace in the Sargasso Sea to live and grow in freshwater habitats. Again, regulation came only after significant damage was done to the eel population.

After hearing Dian’s story and considering the sorry state of the eel population, I wondered if eels still wriggled in abundance along the shore to feed on horseshoe crab eggs. I set out for the Delaware Bayshore with some possibly less free-range, but equally game, young companions to give eel-catching a try.

Rather than a trench and bare hands, we opted for the better odds of a seine net.

It was high tide in early June, with a modest amount of horseshoe crabs spawning on the beach – not so many that netting would be impossible, but hopefully enough to pique the interest of eels.

One friend held the end of the net on shore as I pulled the other end out into the water, arcing the net onto shore further down to corral the knee-deep water along the beach. After pulling the net ashore to assess our catch, we were astonished.

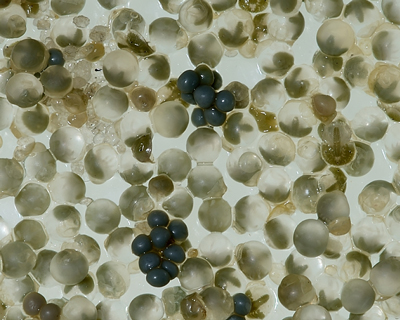

Not only was there a writhing pile of eels, there was a who’s who of commercially and recreationally important fish, including striped bass, weakfish, flounder and Atlantic croaker. There were also blue crabs and smaller fish including striped killifish and Atlantic silversides. A few more net pulls yielded even more fish and eels.

We can’t be sure these fish were there in the shallows because of the spawning crabs, but research on fish diets has shown that all of these species have turned up with horseshoe crab eggs in their stomachs.

And it’s not just the eggs. Throughout the summer and fall, larval and early life stage horseshoe crabs swarm the shallows. These morsels are no doubt gobbled up by fish as well.

The massive energy jolt of horseshoe crab eggs and young could be key strand in the coastal food web, but there have been no studies geared toward determining their importance to fish populations.

The decline in crab numbers caused a decline in shorebird numbers due to reduced horseshoe crab egg availability. Were any fish populations affected in a similar way?

Horseshoe crabs occupy other notable links in the food web as well. A few anecdotes report horseshoe crabs turning up in alligator and shark bellies. But neither of these large toothy animals is known for being a picky eater.

One sea-beast that may truly depend on horseshoe crabs for food is the loggerhead sea turtle. Thousands of these turtles migrate to the Chesapeake and Delaware Bay in summer to feed on the crabs. It is now thought the loggerheads are suffering from a lack of horseshoe crabs in the Chesapeake.

This is because after horseshoe crab overfishing took a toll on the population there, the turtles increasingly switched to blue crab. As blue crab populations declined due to overfishing, loggerheads switched to a diet of fish. But as their diet shifted to fish, the turtles began to become a nuisance, vandalizing commercial crab traps and raiding fishing nets in their efforts to get at the catch.

Even though the harvest of horseshoe crabs is now regulated, most populations are continuing to decline. It’s unclear why this is the case, but there is increasing concern that the industry which uses horseshoe crab blood for medical testing may be taking a toll. A component of the blood that is highly sensitive to the presence of bacteria is under ever-increasing demand, while the population of crabs to draw this blood from is decreasing.

We already know that loggerhead sea turtles and shorebirds such as the red knot depend on horseshoe crabs. Given that these two species are also on the Federal Endangered Species list, the mandate to maintain a healthy horseshoe crab population is clear.

We already know that loggerhead sea turtles and shorebirds such as the red knot depend on horseshoe crabs. Given that these two species are also on the Federal Endangered Species list, the mandate to maintain a healthy horseshoe crab population is clear.

As amazing as horseshoe crabs appear to us when on shore, they undoubtedly have many more amazing tales to tell us from under the sea. Discovering these new stories will help us understand both the importance of horseshoe crabs in marine ecosystems as well as the increasing importance of conserving them.

If you happen to live near a horseshoe crab spawning site, it is easy to pitch and help. There are crab flipping programs and spawning crab surveys that rely on volunteers. Finally, think of the horseshoe crab any time you go to the doctor. Anything injected or implanted in our bodies is first tested for contamination with horseshoe crab blood. Take this as a reminder that we too depend on horseshoe crabs and each of us has a stake in their continued survival.

are they protected

Hi Joe,

It was nice seeing you again at the Reeds Beach house.

Thanks for recognizing me and my “pack of kids” in your informative article on horseshoe crabs. I enjoyed the article and got a kick out of your acknowledging me.

Dian Shivers

So much to think about!!! Fascinating to see how diverse the catch was in June with the seine net — I had no idea there was so much life so close to shore. Thank you for sharing all this with us!

Wonderful article, Joe. Thank you as always.

I have spent most of my 70 years at Reeds Beach NJ. I spent my Summers here with my grandmother and I can tell you that the horseshoe crab is not as nearly as plentiful today as it was when I was a child. Also, I caught eels all the time as a child, but now they are far from abundant. I have caught eels, stripers and many other fish that were loaded with horseshoe crab eggs. It is a sad commentary on what has happened to the species. I still spend my Summers at Reeds Beach and marvel every year how important the horse shoe crab to birds and fish.