Sometimes, science requires that you get dirty. And hot. Really hot. As graduate students, we never imagined that climate change research would lead to us plowing a rural Indonesian farm field in 96 degree Fahrenheit heat, topped off with 98 percent humidity. But here we were.

And 10 minutes earlier, we had each swallowed a high-tech temperature sensor pill, like something out of The Matrix.

Can Forests Help Keep Us Cool?

It all started with a simple idea: deforestation might lead to hotter local temperatures, which might increase the risk of heat illness in communities living in or around those forests. It seemed obvious to us that cutting down trees — which provide shade and can cool local temperatures via evaporation and transpiration — may lead to hotter microclimates and in turn impact people.

But when we reviewed the peer-reviewed literature, there wasn’t a lot of evidence for these links. This gap raised several questions about how people living in rural developing countries might adapt to temperature increases driven by deforestation and by climate change. We also wondered whether human alteration of the environment that exacerbates or accelerates these temperature increases would impact people’s livelihoods and daily lives.

So, we set out to explore whether there is any plausible link between deforestation, local temperatures, and heat illness risk. But we were new to this area of research and had loads of questions about the best ways to measure temperature, heat illness risk, and productivity. Our collaborators at the University of Washington School of Public Health introduced us to the many high-tech tools for gathering these data, which all involve advanced sensors.

Enter the Matrix pills.

The average human core body temperature should be around 98.6 degrees Fahrenheit, but that can vary from person to person. We needed a way to gather continuous measurements, so we could track how core body temperature changes during physical activity under changing external conditions. And the classic oral thermometer wouldn’t work, because it’s is infeasible and disruptive to stop someone every minute to take their oral temperatures.

Then we learned about a high-tech way to measure core body temperature: the CorTemp Sensor pill. When swallowed, these vitamin-sized pills measure core body temperature every 10 seconds, and then wirelessly transmit that reading to a data logger that is worn on the hip. But how well did they work?

Adventures in Self-Experimentation

Six months later we were standing in the middle of Long Duhung village, sweating profusely, holding the CorTemp pills in our hands. When it came time to actually swallow them, they were big but went down easily.

We had come to Berau, in Indonesia’s East Kalimantan province, to start scoping out our plan for field research. And so it was time to swallow the pills. We also strapped on heart rate monitors to measure physical exertion, and high-tech pedometers that measured the movement of our bodies along three axes as we worked. Lastly, we set up two sensors to measure the air temperature as we worked: an ambient temperature sensor and a Wet Bulb Globe Temperature (WBGT) sensor, which accounts for both solar radiation and humidity.

Then we grabbed two hoes, and set out to see just how hard it was to work outside in the sun in the non-forested tropics.

Walking to the edge of the village, we offered to help a local community member plow her field. She kindly accepted our help, and brought along a small crowd of friends to watch us — from a shady, relatively cool spot under the trees. Apparently, we were the day’s entertainment.

It was hot — the humidity enveloped us like a heavy, sodden blanket and the sun beat down on our heads. We deliberately decided to work outside at solar noon, the hottest time of day when the sun is at its highest point in the sky. And we were quickly regretting that decision.

We wore hats to get some shade, but we found ourselves taking breaks and slowing down. Our hands, better suited to typing furiously on our keyboards, were blistered and raw within 15 minutes. Our clothes hung heavy with sweat, and we had to grip the plows tighter so we wouldn’t lose control with our damp hands. The repetitive motion — raising the hoe up, swinging it down into the dry soil, and lifting the soil to create raised beds — was both mentally and physically exhausting after 30 minutes. The tracker on our wrist and waist logged every exhausted swing. And despite our best efforts, we could hear amused muttering from the audience as they relaxed in comfort under nearby trees.

After about an hour we took a break and sat in the shade with local community members. The trees really did provide cooling services — the shade felt at least 5 degrees cooler than the fields. While active we didn’t feel an urgent need to drink water, but once we stopped we both guzzled all the water we could get our hands on. In all, we only plowed two rows in a field that could fit about 15, a small fraction of a normal day’s work for these villagers.

This ad-hoc self experiment taught us a few lessons. First, mechanical farming equipment is hands-down the best invention of the past century. Second, while we have all worked or exercised out in the sun during the hottest time of day, the conditions in the tropics were a whole new level of hot. And the data we gathered backed up just how drained we felt.

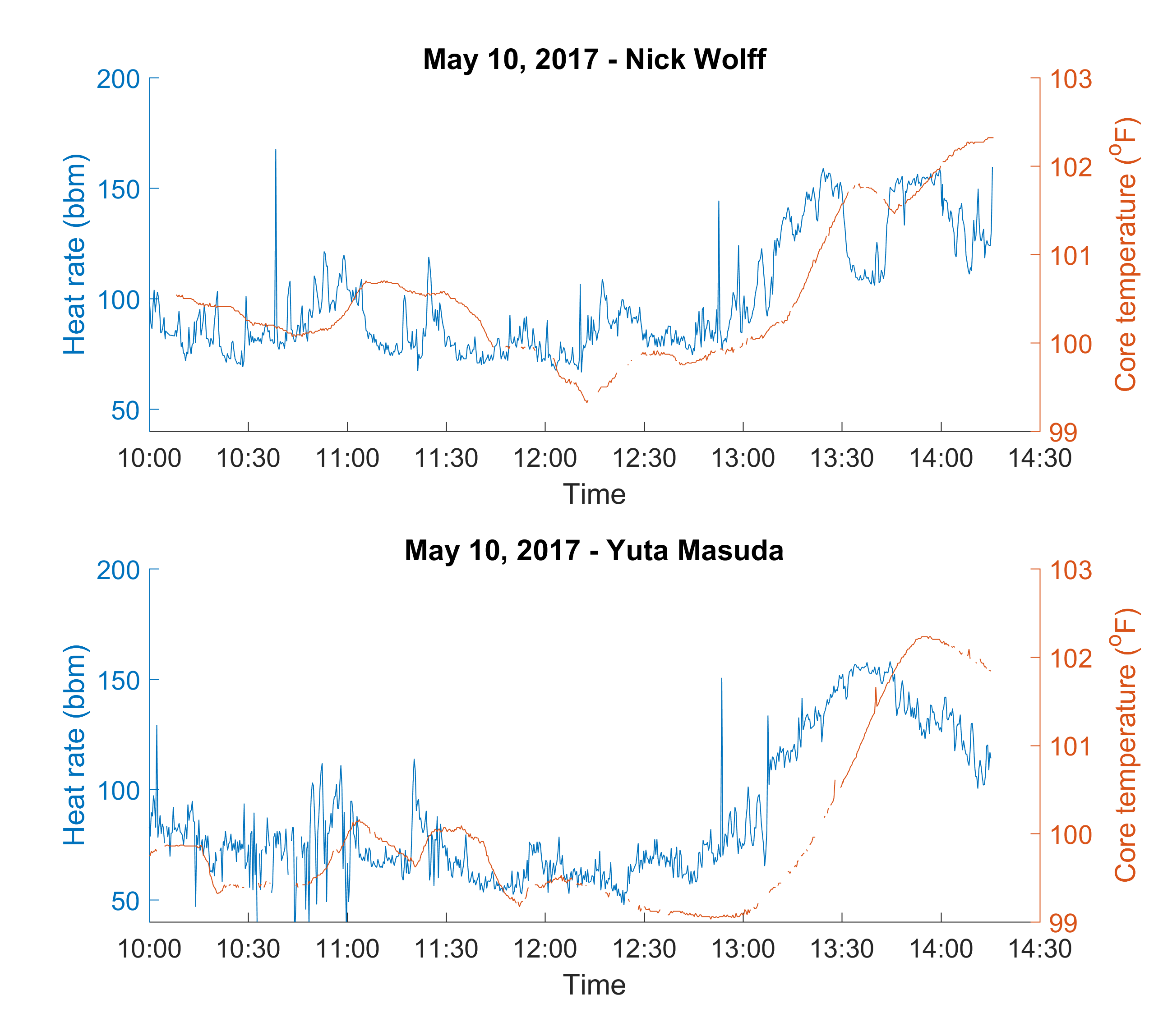

For most people, having a core body temperature over 101.3 degrees Fahrenheit puts them at risk of heat illness, and the longer they’re over that threshold the more they are at risk. We started working at around 1pm, and within half an hour, both our core body temperatures were well over 101.3. And our core body temperature continued to rise even after a short water break.

Our heart rate increased rapidly above our resting heart rate, which was around 60 and 80 beats per minute for Masuda and Wolff, respectively. We also saw our movement slow down with time.

The kicker? We only worked for an hour.

The kicker? We only worked for an hour.

The bottom line is that outdoor manual labor in the tropics is difficult, and in our own personal experience it is plausible for people who work long hours in the tropics in the sun to be at risk of both heat illness and decreased productivity.

This experience helped us refine our questions about how forests and climate change can impact local communities, their health, and their livelihoods. Will people adjust the number of hours they work, when they work, or the activities they engage in as temperatures increase? If forests cool surrounding areas, how large and dense should the patch of forest be to provide a noticeable cooling effect? Can better landscape design help people adapt to climate change?

The questions we’re exploring are relevant for some of the world’s most vulnerable populations, and they have to be answered if we are to find sustainable and natural methods to adapt to climate change. In the short-term, the cooling services provided by trees may be critical for the health and livelihoods of these communities. Hopefully we’ll be back in Indonesia soon to advance our understanding of how forests, work, and health are linked in hot, humid, tropical climates.

But I don’t think they’re going to let us work the fields again. And we really don’t mind.

I know you did this experiment to make a point, but anyone who ever picked crops in the summer knows that the sun is hot and makes working uncomfortable. I only wish that every city dweller who never thinks about how food gets to grocery shelves and restaurants would spend as much as an hour out in the fields in 80 degree + weather. They might gain some respect for our migrant workers as well as those who work for little pay in other countries. If they could connect the dots from the destruction of forests to things like soil erosion and rising temperatures that would be great!

Thanks for proving what some people still refuse to recognize!

Did no one who is actually a resident/native agree to take a pill and be monitored?

Hi Frances, Thank you for the question – see this segment of a comment from the authors, I believe it answers your question: “We had hoped to conduct a preliminary experiment much like the one you suggest using the CoreTemp pills before working in cleared and forested landscapes, but given a feasibility assessment we determined to use an alternative method to measure core body temperatures for our comprehensive fieldwork to study the relationship between deforestation, temperatures, and heat illness risk in August.

We took the pills ourselves out of curiosity and used the results to post the human interest story to illustrate the challenges of working outdoors in the tropics in a non-forested area – and we learned from focus group interviews that, in fact, the temperature and solar radiation is a cause for concern for those working in open areas outside during the hottest time of day. We are looking forward to sharing more posts in the coming months that will highlight our scientific results from the larger study.”

I recently attended a lecture at the Witte Museum in San Antonio, Texas on the environment and health. They showed an aerial view of the tree canopy in Bexar County and then showed maps on health disparities, including longevity. Although causation is hard to prove, the correlations are stunning. There is certainly no harm to keeping trees unless you are allergic to them.

Live in Baltimore, ms13. Mission to reforestation, on state highway and country roads.when you walked into forest to cool off, do you remember the taste of the pure air, refreshing cool air you can actually feel going into your lungs. Did you happen to learn why mature trees in the rain forest are dying?

You know, this would have been a much better “study” if you had put those expensive pills in 2 acclimated workers for a day, one working in the field, one in the forest. So, what you have actually found is that 2 urban professionals from a temperate climate can develop heat stroke at noon in the tropics if they perform physical activity. Oh, and shade is nice.

I am sorry, but this is self aggrandizing fluff. Do better. Please. Flying you there damaged the environment, making your gadgets damaged it. At least make it count for something worthwhile, or admit you are just tourists on vacation and don’t actually care. This pseudo science is painful and part of the problem.

Dear Brandy,

Thank you for your feedback. We share your concerns about emissions and we are both committed to minimizing our carbon footprint. The scoping trip we report on here was an important component of a larger scientific study involving a team of scientists in collaboration between TNC – USA, TNC – Indonesia, Mulawarman University, University of Washington, and the Berau District Government. Although we conduct most of our meetings via Skype, the scoping trip was necessary for us to meet stakeholders, field test equipment and engage with the villages where we will be working more intensely during our primary fieldwork in August.

We had hoped to conduct a preliminary experiment much like the one you suggest using the CoreTemp pills before working in cleared and forested landscapes, but given a feasibility assessment we determined to use an alternative method to measure core body temperatures for our comprehensive fieldwork to study the relationship between deforestation, temperatures, and heat illness risk in August.

We took the pills ourselves out of curiosity and used the results to post the human interest story to illustrate the challenges of working outdoors in the tropics in a non-forested area – and we learned from focus group interviews that, in fact, the temperature and solar radiation is a cause for concern for those working in open areas outside during the hottest time of day. We are looking forward to sharing more posts in the coming months that will highlight our scientific results from the larger study.

Nick and Yuta

I once saw a photo of trees taken with infra-red sensitive film. The foliage looked white, brighter than fall foliage in New England. If trees reflect infra-red light it may explain why past periods of high CO2 in the atmosphere (if they occurred) did not result in catastrophic global warming.