It takes real skill to catch a sea turtle…. Especially when you have to wrestle it out of the water.

Cruising over coral reefs and seagrass meadows in the Arnavon Islands, I watch as the conservation rangers in the bow yell and point; first left, then right, then left again as a young green turtle bobs and weaves below us, trying to outrun our boat. After 10 minutes the turtle tires and we slow, the outboard dropping to a dull rumble. Andre Robo stands barefoot on the narrow bow, peering over the edge, one hand out for balance and the other gripping the rope like a cowboy holding the pommel.

He crouches low, waiting for the perfect moment, and then rockets off the edge like a swimmer diving in for a race. The driver cuts the motor, swerving away. We wait… seeing nothing but a dark shape and green shirt against the reef. Seconds later he bursts to the surface — frantic turtle held aloft — and we all cheer.

We’ve caught the first turtle of the rodeo.

Here in the Arnavon Islands, community conservation rangers and Nature Conservancy scientists are catching juvenile green turtles — a process nicknamed “the turtle rodeo” — as part of a long-term tagging program to gather data on growth rates and raise community awareness for turtle protection.

A Safe Haven for Greens in the Solomons

The green sea turtle, Chelonia mydas, is an endangered species found in tropical seas around the world. Primarily herbivorous, adult turtles graze like underwater cattle on seagrass meadows, trimming the vegetation and keeping the plants healthy.

Juvenile greens have a beautiful brown-and-olive carapace, but the species is not named for the color of its shell. “Green” refers to the thick layer of greenish-tinged fat and flesh beneath the carapace. Green turtles are part of a traditional diet for many coastal communities across the world, many of which still harvest sea turtles for food. (In Solomon Islands, the nickname for the species is “Solomon’s beef.”)

But the bigger threat to greens — and the cause for the species’ catastrophic decline — remains the illegal wildlife trade. Unlike hawksbills, which are valued for their mottled shell, greens are typically poached for bogus medicinal benefits and a trade in their meat and protein-rich eggs. Like other turtle species, greens are also threatened by death in fishing nets, pollution, and habitat destruction.

In the Solomon Islands, green turtles have a safe haven in the waters surrounding the Arnavon Community Marine Park (ACMP). A multi-hour boat ride from the mainland, these four palm-strewn islands in the middle of the Manning Straight are a critical foraging ground for juvenile green turtles. With help from The Nature Conservancy, they also recently became the first national marine park in the country.

“The Arnavons is known for nesting hawksbills, but we also have foraging juvenile greens and very low numbers of nesting greens,” says Richard Hamilton, the Nature Conservancy’s Melanesia program director.

Just one out of every 100 nesting turtles is a green, but the seagrass meadows and fringing reefs are teeming with juveniles. ACMP rangers from the three closest communities manage the islands, monitoring turtle populations and protecting turtles from poachers, which are still an ever-present threat.

Since 1992, rangers and Conservancy staff have conducted a green turtle tagging program to gather data on the local population. Nearly half of the population is tagged and frequently recaptured, providing a wealth of data on the growth rates of young greens.

Rodeo on the Reef

After an hour’s work, two turtles lay slapping against the boat’s hull, and ranger Leslie Rubaha has just landed a third (after a few failed attempts). He swims the turtle towards the boat, careful to keep its powerful flippers out of the water. Another ranger, Siroko Tebakota, carefully lifts the turtle into the boat by its front flippers and then places it on its back. The driver revs the engine and we turn back, speeding towards the Kerehikapa field station.

Once on shore, the rangers carry each turtle out of the boat and place them carapace-down on the sand. Conservancy marine scientist Simon Vuto flips the first one over, holds it down firmly, and motions for me to get to work.

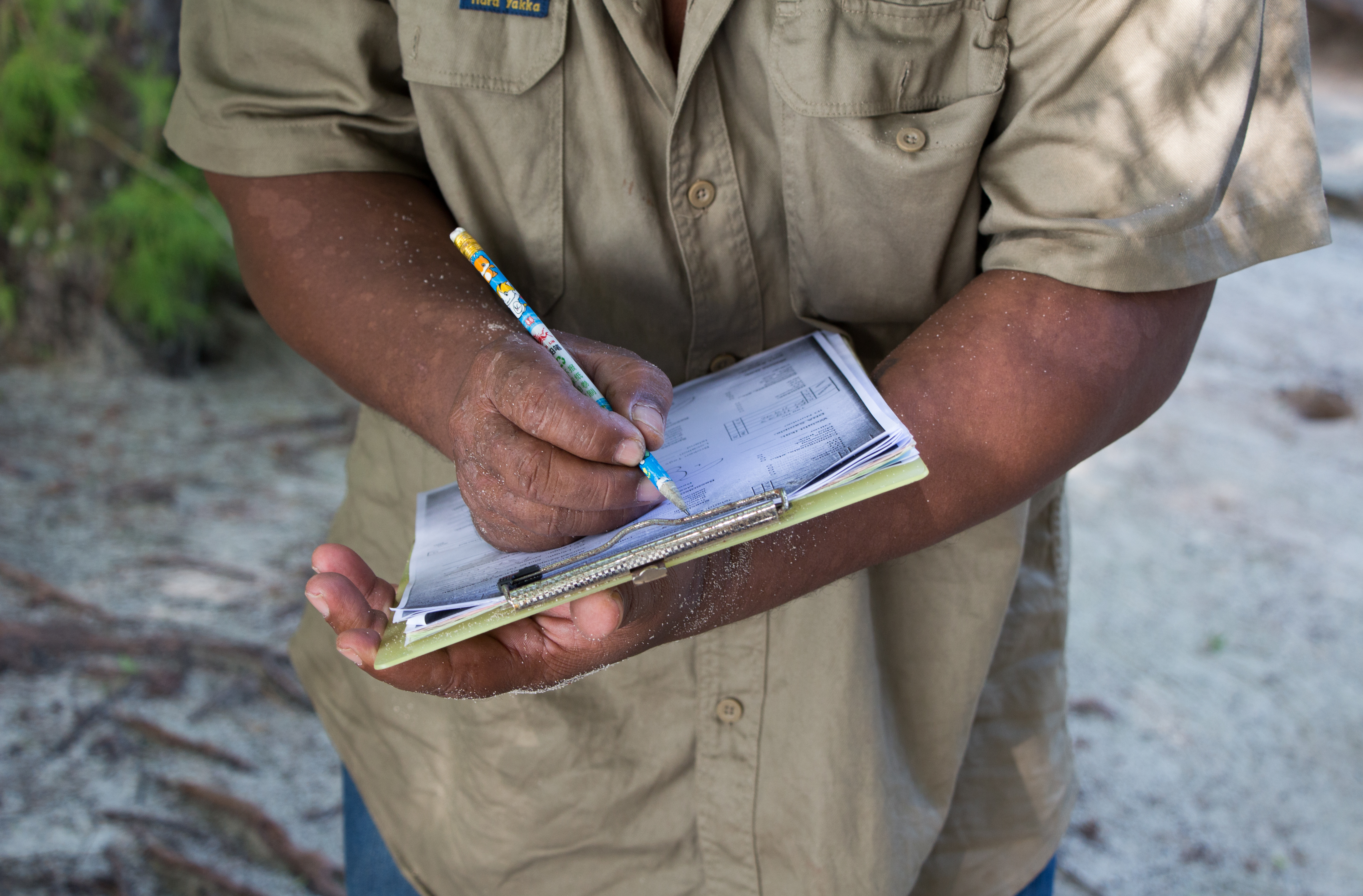

Following instructions, I stretch a pink measuring tape across the smooth, olive-green shell, measuring the length and width of the carapace and plastron. Standing behind me, Franis Routanis records the numbers on a data sheet: 46.5 cm, 45.5 cm, 37.5 cm. Then we inspect the turtle for any characteristic markings, like scrapes and notches in the shell or barnacles. Another turtle, slapping away a few feet from my legs, is missing its right hind flipper, possibly bitten off by one of the crocodiles lurking in the mangroves.

As a final step we attach a small, titanium tag to each flipper. Vuto pulls two tags off the loop — RI-11942 and RI-11943 — and clips the first into something that looks exactly like a leather-punch. I slide the opening over a bit of soft flesh between the scales on the flipper’s rear edge, close to the turtle’s arm pit. “Just push hard once, ease off a little, and then give it one final press,” says Hamilton.

I clamp the handles together, like an oversized staple, and with a slight crunch the tag’s pointed end slides into the flipper. It’s over within a second.

Another quick punch to the opposite flipper and we’re done. We flip my turtle over again and move on to the next, working quickly to reduce the amount of time the turtles are captive and stressed.

A Big Payoff for Moderate Sized Protected Areas

As the rangers work through the remaining two turtles, Hamilton tells me that the turtle I just tagged is likely about 10 years old, based on its size. “We have a remarkably resident juvenile foraging population,” he says,” with some turtles staying in the Arnavons more than 10 years.”

These data align with other green turtle monitoring programs in Australia and elsewhere, revealing that juvenile green turtles take a tremendous amount of time to reach maturity. The average Arnavon’s green grows just 1 centimeter per year (carapace length) as juveniles. They undergo a small growth spurt in their teenage years, when they are around 55 to 65 cm in curved carapace length, increasing to a rate of up to 2 centimeters per year.

With such slow growth rates, these juveniles spend over a decade in the ACMP, which at 152 square kilometres is relatively small compared to other marine protected areas.

“Our data really show that even moderate-sized protected areas can protect juvenile populations for a significant portion of their lifecycle,” says Hamilton. He also credits the tagging program with raising community awareness about green turtles, especially in an area where sea turtles are still caught and consumed for food.

Hamilton says that previous genetic research by scientist Damien Broderick indicates that these juveniles come from Micronesian nesting grounds, suggesting that upon reaching maturity they will migrate back to their natal nesting beaches — a journey of more than 1,000 miles.

Even moderate-sized protected areas can protect juvenile populations for a significant portion of their lifecycle.

Richard Hamilton

With the tagging done, it’s time to release the turtles. We each grab a turtle by the carapace — enduring painful slaps to our legs and arms — clamber down to the water’s edge. I wade in knee-deep and attempt to place the turtle gently beneath the surface, but the minute its flippers are submerged it tears itself from my grip and swims straight out into the bay, flippers beating winglike beneath the waves.

Perhaps in another few years, the same turtle will make another appearance at the rodeo.

Join the Discussion