Migration is a dangerous undertaking. For conservation efforts to be effective, scientists need to better understand just what threats birds face along the way, and how those obstacles are changing in an increasingly human-dominated world.

A new paper from Smithsonian, Nature Conservancy, and other agency scientists assesses the state of the science on bird migration across the Gulf, and identifies both research gaps and new technology that can help fill them.

Mysteries on the Wing

Each spring and fall, neotropical songbirds amass by the millions to migrate between North and South America. Warblers, vireos, and other passerines typically fly across the Gulf in a single, brutal 18-to-24 hour flight, while raptors circumnavigate the Gulf’s western shores.

Many birds don’t survive. By measuring populations at the breeding and wintering grounds, scientists know that the majority of mortality for these species occurs during migration. What obstacles do these birds face along their journey, and just how, when and where are these birds dying?

“Migration is still a bit of a black box,” says Emily Cohen, a researcher at the Smithsonian Migratory Bird Center (SMBC) and lead author on the research. “For nearctic neotropical long distance migrants, we just don’t have a holistic picture of sources of mortality during the migratory periods.”

Scientists from the SMBC, The Nature Conservancy, and their colleagues set out to assess the state of the science surrounding bird migration in the Gulf. Their paper, published recently in The Condor, outlines what is known about major events and obstacles facing neotropical migrants, identifies research gaps, and reviews emerging technology that could help fill those gaps.

Migration is still a bit of a black box.

Emily Cohen

A Region-Wide View of Migration

Much of what scientists do know to date has focused on either specific species or specific locations. The exact movements of American redstarts during migration, or the use of a particular stopover site are both key pieces of the puzzle, but they don’t reveal the bigger picture.

“There haven’t been a lot of region wide studies, either on the whole migratory route of a species or the movement of all species,” says Cohen. “Now we have the tools to do this quantitatively for the first time on a large scale.”

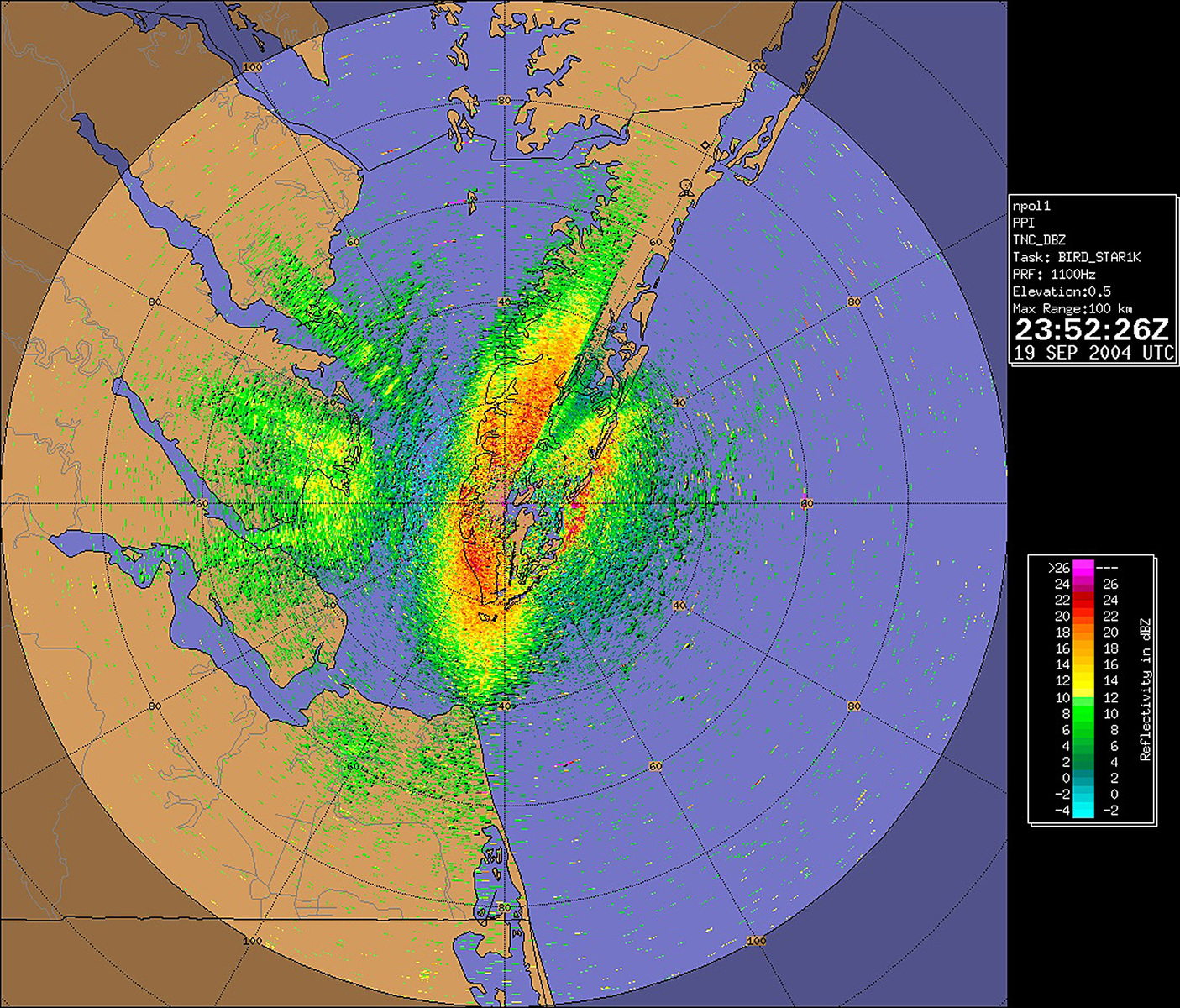

Two complementary new datasets could help unlock some of those questions — radar imagery and citizen science. Amazingly, bird migration is so massive that it can often be picked up on radar networks. “You can use radar data to look at birds moving through the airspace or even lifting up from stopover habitat,” says Cohen. “And the data source is phenomenal, because it’s consistently collected, archived, and freely available.”

The researchers propose that radar data will be a key tool in both identifying and characterizing stopover habitat — particularly in the less-studied areas of Mexico and the Caribbean — and understanding how consistently those locations are used over time.

It can also help scientists map airspace. For migratory birds the air itself is habitat, but one that, until recently, has been largely overlooked and under-studied. And like habitat on land, airspace is increasingly threatened by flight paths, buildings, light pollution, wind development, and even drones. Radar data can help map this habitat and allow scientists to better understand how birds are using it.

The second data source is just about the exact opposite of region-wide radar: the birder’s checklist. The citizen science platform eBird allows birders across the country to log checklists of where and when they see an individual species. Pooled together, these data are an incredible resource for scientists to better understand species distributions, their associations with particular landscapes, and the timing of their migrations.

The Population Perspective

Cohen explains that another key research gap is knowledge about populations of a specific species. Wood thrush populations are declining rapidly, but that decline is not even across their breeding range. Data from the North American Breeding Bird Survey show that populations in the western part of the range (Missouri, Wisconsin, and parts of Illinois) appear stable or increasing, while in much of the northeast and southeast their numbers are plummeting.

It’s possible that these populations also have different wintering grounds or migratory routes, where threats could be contributing to an en-route decline to the breeding grounds. For this species, scientists recently discovered that they follow different migratory routes each season, flying south along the Florida peninsula in fall and then making landfall in coastal Louisiana on their way north. “So we need to have migratory connectivity information to put it into perspective in a population context,” says Cohen.

Cohen and her colleagues at SMBC are using the new method of stable isotope analysis to start asking those questions. At banding stations in coastal Texas, SMBC field teams collect a single tail feather from each bird they catch and band during spring migration. “That tail feather holds the isotopic signature of where the feather was grown,” says Cohen, “and they’ve carried that feather since the previous breeding season.”

Cohen and her colleagues analyze the isotopic ratio of hydrogen in the feathers. These ratios change with latitude, which provides coarse-scale information about where that individual bird bred the previous summer. “It won’t tell you Washington DC versus Baltimore,” she says, “but it can tell you Canada’s boreal forest versus Michigan.”

The Holy Grail of Migration Science

Another puzzle is working out exactly how many birds die en route to the breeding or wintering grounds, and where that mortality occurs.

“Some new technology has come along that is helping unravel that question,” says David Mehlman, former director of The Nature Conservancy’s migratory bird program and co-author on the research. “Nifty things like light-level geolocators and smaller and lighter radio transmitter technology are letting us track these small birds over long distances.”

Tracking technology is always limited by the size of both battery and bird. Batteries need to be large enough to gather data for long periods of time, but small enough not to hinder — or exhaust — already-taxed and often tiny migrant species.

Increasingly smaller batteries are allowing scientists to track smaller species, a trend which the researchers expect to continue. But they come with a high price tag, and the need to re-capture the bird to retrieve data. “They’re great at helping us understand habitat quality and population-level distributions,” says Cohen, “But they don’t tell you where birds die, which is sort of the holy grail.”

Other technological advances might improve the situation by taking advantage of existing infrastructure to retrieve data from passing birds. “It’s within realm of possibility that we can have networks of radio receivers spread across the Gulf that would passively intercept tagged birds,” says Mehlman.

Clear identification of these research gaps — and the technologies that can help fill them — can’t come soon enough. “We’ve known for many years that populations of neotropical migrants are declining,” says Mehlman, “but the challenge is that there are multiple things going on.”

Justine you are a Angel from God and a protector of the birds.keep researching writing and educating our world about our beloved neos.your hard work is much appreciated.some ones got to protect them.I hope soon you will stand before congress and explain and show them the beautiful birds and their fight to survive and their struggles they must endure in a changing world.it’s bad enough what they must endure from mother nature but we can try to help them by removing the man made problems that make it even more difficult for them.like the lights of the building.one more bird saved means they have a chance to survive.God bless you and st Francis pray for you.

Update education the populous about our neo friends does work.American national insurance co has agreed that neo tropical birds are important and they will turn off lights here on out during migration season’s.apparently the storm they were fighting and lights were cause of 400 dead neos.corpus Christi is another area of tall buildings and also needs to cut lights off during migration.the wind mills are the no one thing I feel must be dismantled especially on coast of Texas.they have a huge amount of them near isolated areas at coastline at kingsville Texas on a huge ranch called Kenedy ranch. I believe.this is a major fly way area for all migrating and local birds.I hate to say this but the so called people who are thinking they are saving the planet with their clean energy plan are wiping out our wild life.same thing with bio fuels.ranches that use to make it with cattle are now leasing lands to grow corn for bio fuels and wind farms.the fertilizers from thousands acres of corn I believe end up in water sheds and end up in bays like the famed baffin bay of Texas (a unique fishing area that has seen unprecedented algae blooms from nitrates I presume from fertilizers that cause fish kills from low oxygen caused by red tides.so we must do a better job of conservation I feel.natural gas is plentiful and less destructive I feel to planet.oil companies have their droughts but they do lease thousands of acres and don’t developers it with houses and commercial properties.the oil co have money and resources and can do much more good than these so called planet friendly green people.just imagine how much help these companies can do.people always criticize them but I’ll guarantee you most santuaries are funded by them.look at high island Texas a major fly way for neos and rest stop.major oil companies donated refuge and fund it.so the green people I feel need to dismantle the windmills and get rid of bio fuels.that’s what the focus should be.God bless our birds and wild life and planet st Francis pray for our wild animals and birds

Our neo tropical darlings are in major trouble and congress needs to act now.the wind mills need to be dismantled.they are killing machines.tall buildings need to turn off lights during migration.(recently400 neotropicals killed when hit the American national insurance building one night at Galveston Texas coast.imagine making the whole brutal journey across the gulf of Mexico only to hit a building and dying.they had lights on.neo tropical stop over habitat being destroyed at Texas coast.recently Texas atm at Galveston wiped out a whole grove of mulberry trees.these rest areas provide important food sources(berries and rest).mulberry trees should be federally protected.there is still orchard left there but it’s now be threaten by more development.these trees only grow seven feet every ten years.these trees and resting areas are vital after long journey over gulf of Mexico from Yucatan while neos are coming back for spring to north America from tropics especially if a wave of birds encounter terrible coastal spring storms like cold fronts.they need these habitats.more protected reserves are needed here and protected from development.the wind mills must be dismantled in gulf coast areas immediately..another good ideal would be oil rigs in gulf that aren’t producing and abandoned could be utilized.they could hold watering stations and possibly have vegetation like mulberry trees are other types of food plants that could offer food and refuge from storms in gulf during spring.I spend a lot of time in gulf and have seen many wore out birds from fighting storms land on boats.it’s terrible.they are so worn out hungry and dehydrated.many die trying to drink salt water.I might sound weird but it’s true they need rest areas in gulf during storms.a cistern system would be good but it would have to have automatic flushing device or a small drip hole with no pool so salt from ocean spray would contaminate it.I don’t know just a thought.they are currently tearing down abandoned oil rigs that could be made bird rest areas.God bless our neos st Francis protect them and congress.