Behavioral science and economics have provided important insights for health, finance, and many other domains, but are largely untapped resources for conservation. A new paper in Conservation Letters helps practitioners tap into behavioral sciences.

Poverty and the environment are twin problems. We’ve realized that we need to solve them together. One solution we’ve tried is giving people ways to earn money that doesn’t hurt the environment.

Over the last decade or so, there has been a lot of interest in this type of thing—when I say that I mean that hundreds of millions of dollars has been spent on these programs worldwide. So it was really important to understand whether these programs were working.

Before I joined The Nature Conservancy (TNC), we went to the Republic of Kiribati to do just that. The 33 atolls of Kiribati are scattered across an area of Pacific Ocean the size of the United States.

Kiribati is a sort of laboratory because the economy is based on two things: fish and coconuts.

Some of the islands in Kiribati were getting very crowded. Many more people than ever before were trying to feed their families from fishing on the coral reefs. On these crowded islands, the coral reefs were under a lot of stress. The reefs were changing. There were fewer big fish to feed everyone.

When families aren’t fishing, they spend time harvesting coconuts on their own land and selling them to the government, which exports the crop. Selling coconuts is the only source of cash for most families.

As part of a social welfare program, the government increased the price paid for coconuts by 30%. Imagine getting nearly a 30% raise in your salary!

Our failure to identify the appropriate approach for behavior change is a major impediment to solving conservation problems and achieving better outcomes for people and nature.

The Ministry of Fisheries supported this price increase because they thought it could increase incomes and reduce fishing.

This reasoning was based on standard economics: if people could earn more for the coconuts, then they should harvest coconuts more, fish less, and this would take stress off of the coral reef.

To test the effect of the price increase on the health of the coral reef and people’s incomes, we went all over the country, by boat, by canoe, by prop plane. During this odyssey, we spent weeks mostly underwater diving and spearfishing to collect data and we surveyed hundreds of families.

When we had a day off, Mwai, my local collaborator, and I inevitably found ourselves out on the ocean. We had a mutual love of fishing and the water.

Finally, back at home, we crunched the numbers, and this is what we found:

![Kiribati fisherman. Photo © Department of Foreign Affairs and Trade [CC BY 2.0], via Wikimedia Commons](https://blog.nature.org/wp-content/uploads/2017/01/Kiribati_fisherman_10706973774.jpg)

The men and women we talked to were earning more money in less time. This meant that they had extra time. And, what did they want to do with that time?

Go fishing.

Mwai was a case in point.

When I revised my standard economic model to account for the fact that people enjoy fishing and that their decisions are driven by personal motivations and by their culture and not just money, it all made sense.

What we learned from the experience in Kiribati was that, if our assumptions about human behavior are wrong, well-intended programs can backfire and actually fuel further environmental degradation and poverty. This lesson has sobering implications for the hundreds of millions of conservation dollars that have been spent on this type of program around the world.

A Major Impediment to Solving Conservation Problems

The lesson I learned in Kiribati brought me to behavioral economics and to a larger problem:

Our failure to identify the appropriate approach for behavior change is a major impediment to solving conservation problems and achieving better outcomes for people and nature.

This is a tough problem because human behavior is complex and messy.

People make a countless number of decisions every day, across the globe, in different cultures and contexts. These decisions include everything from what milk you buy, to how much fertilizer a farmer applies to his cornfield, to whether to drill in the Artic.

On top of that, these decisions are affected by values, beliefs, knowledge, prices, budgets, technology, laws, customs, social norms, emotions, what you did yesterday, and many, many more factors.

Given the large range of actors, behaviors, factors, and contexts to consider, it is not surprising that over time there has been a proliferation of models that try to explain human behavior.

![Coconut palms in Abaiang, Kiribati. Photo © Flexman (Own work) [CC BY-SA 3.0], via Wikimedia Commons](https://blog.nature.org/wp-content/uploads/2017/01/Abaiang_top_view.jpg)

Tackling the Complexity of Human Behavior

Despite the mess and discomfort, we need to forge ahead with partners in communities, government, and business to find shared solutions.

We need a science-based way to identify the appropriate approaches to encourage durable conservation behavior that helps people and nature thrive.

To help us do this, we—and I say we because it takes a team to tackle the complexity of human behavior—propose a set of guiding questions for applying behavioral insights to conservation policy in a new paper published in Conservation Letters.

The questions aim to help conservation practitioners, scientists, and partners reframe conservation problems as behavior change problems, understand why we behave as we do and what it means for selecting behavior change approaches, and evaluate and improve approaches using behavioral insights.

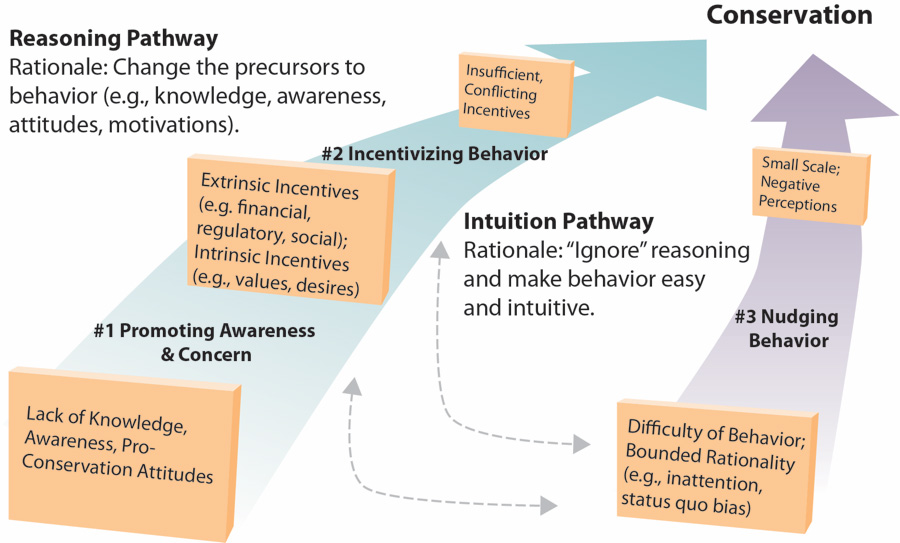

The scientific-basis for these questions is a vast literature on behavior change models and evidence from littering, water and energy conservation, and land management. We help navigate these behavior change models by synthesizing them into three broad approaches.

The first approach is promoting caring for the environment through education and awareness campaigns. However, we’ve learned that caring—or having pro-conservation attitudes—is often not enough.

The current state-of-affairs in the US illustrates what is now a well-known gap between attitudes and behaviors.

The vast majority of Americans say we should do whatever it takes to protect the environment (Pew 2015). But, this proportion shrinks dramatically when we consider the costs and have to actually take action (Pew 2015, LCV 2014, McKinsey 2014, SC Johnson 2011). Clearly, other factors are at play.

On Incentives

This brings us to the second category of approaches: providing incentives—other than caring for the environment—that motivate and align behavior with conservation.

Recently, TNC and other groups have been promoting conservation not just for nature’s sake but also because of the economic or social benefits that nature provides to people.

For example, we’ve been encouraging people to protect coastal habitats, like marshes, not just because they provide habitat for wildlife but also because they can help protect people from floods and storms.

We have done this by putting the value of coastal habitats in economic terms. Through our collaboration with The Dow Chemical Company, we developed new methods for businesses to evaluate how habitats can help mitigate floods from hurricanes. This allowed for side-by-side comparisons with levees, in financial terms that matter to a business.

We’ve taken similar approaches working with communities. And, we’ve seen some surprising things. Communities have picked habitats even when they were the more expensive option!

Of course, communities care about more than costs and flood protection. Many community partners want solutions that also help preserve the natural look and feel that defines their community. And, now-a-days, even for-profit companies are considering both shareholder and stakeholder values.

So, we’re making progress working with businesses and communities by highlighting or providing new incentives for conservation. But, we have to make sure we get the multiple incentives right!

Behavioral Nudges

This brings us to the last category of approaches: behavioral nudges. Behavioral nudges don’t rely on reasoning like the first two approaches. Instead, they side-step efforts to promote caring and provide incentives and they tap into intuition.

Behavioral nudges work by making small changes to a decision context, without restricting choices or changing incentives, such that conservation behavior is easier and more intuitive.

Intuitive decision-making is how people make the vast majority of decisions. It’s automatic. It’s based on gut instincts. In contrast, rational decision-making is deliberate and it’s often based on calculations.

One key lesson we learned from working with businesses and communities faced with flood protection decisions is that the default matters.

When we looked around at flood protection solutions in the US, we found the exception that proves the rule about defaults. Maryland had 10 times more nature-based flood protection solutions than other states. At first we wondered: what the heck was going on!?

Sure enough, Maryland had passed a policy that turned things on its head. It made nature-based solutions the default instead of seawalls or bulkheads. Maryland did so because, without restricting people’s choices, the default could help steer people toward solutions that would be effective for erosion control and enhance the state’s natural heritage. Now it is easy to choose nature-based solutions, and it requires some extra work to demonstrate that engineering solutions are needed in places where the state has already identified as appropriate for nature-based solutions.

Okay, so what have we learned? Behavior change is messy; a one size-fits-all approach is rarely effective and can even backfire. Science is needed to identify the mix of approaches that makes sense for the particular context. Special caution is needed to make sure that one approach does not counteract another (e.g., economic incentives crowding-out intrinsic incentives). Partnerships are needed to design approaches that deliver shared solutions through respect for people and nature.

So, how can we use science to determine which mix of approaches to use? How can we avoid the trap that I fell into back in Kiribati where I did some “arm-chair economics” and then I was surprised by how real people make real decisions?

We need to stop making assumptions and start investing in science to ask key questions about human behavior and nature.

Answering these questions is going to take research and experimentation. It’s also going to take some new capacity both in terms of expertise and in terms of being able to say, “We’re human but we need science to help understand human behavior.”

What an interesting article it is exactly what I want to do as a volunteer Citizen Scientist in Subtropical Moreton Bay, Queensland AUSTRALIA, please let us have more of this type of thinking and aimed at the young people, who are the future.

If anyone has some advice to offer, please feel free to contact me.

Sheila nice article, we will do an op-ed based on our experiences here in Switzerland. Here, conservation is almost entireley focussed on “changing behavior” by repeating the message over and over again. Even in the face of overwhelming evidence that this approach has reached a plateau. Individuals who question are marginalized and even threatened with judicial action… take a read here https://drive.google.com/file/d/0BzPFamJgOYe1OGZoWUs2UGtqcGM/view

Considering the motivations of humans, which are basically existence, growth and expansion ( As every living creature), there will be only one limit to this evidence : Nature. If we manage to expand to other planets, then the race goes on. If not, we can just look at insects in a terrarium when you forgot to put food or water. They just continue eating as usual, and start fighting for the last leaves, and then may eat themselves. Put food again, they reproduce, and thrive again.

Therefore, measures are useless. People will go for environment because their livelihood and existence are threatened, and this is unstoppable. What we can do, in advance, is preparing the solutions that the future will need ^^

The first question is why the fishermen’s environment is getting too crowded?

What ever incentives are used in a logical enlightened way to save the fish population, the number one is population stabilisation. Without that all other measures will fail.