I’m a long-time craft beer enthusiast, but I’ve always avoided the scene that sniffs a brew and pronounces that it smells like “horse blanket” (seriously, I’ve actually heard beer snobs use this term).

I’m a naturalist, first and foremost, and I view my pint glass with a nature lover’s eye. While it may not seem like beer has much to do with biodiversity, that’s not true: Brews rely on plants and land and, perhaps most important, microbes, to make it all work.

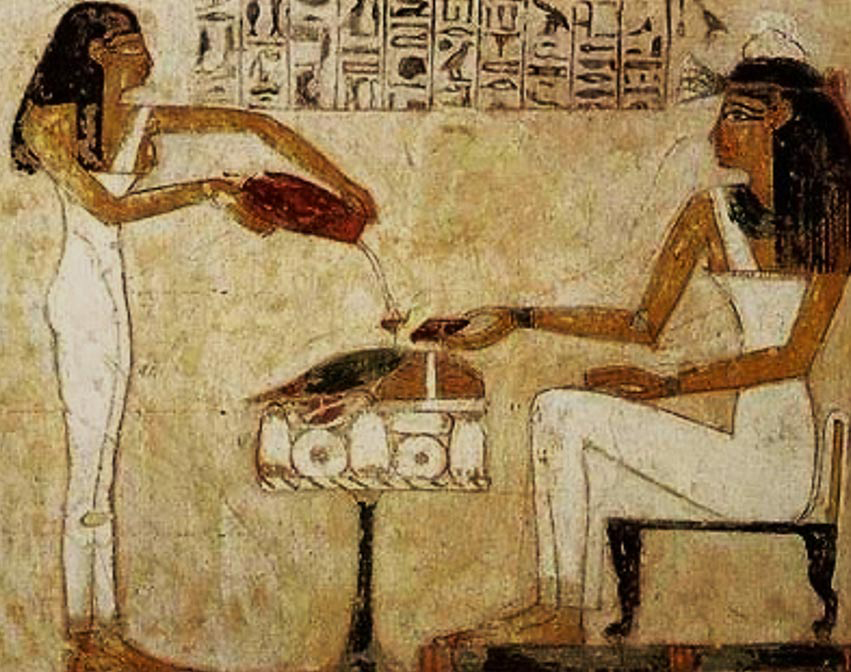

I’m fascinated that people learned how to harness microbes to ferment beverages before they even knew microbes existed. Indeed, fermentation is one of humanity’s earliest endeavors. The essential scientist in this realm is Dr. Patrick McGovern, a biomolecular archaeologist with the University of Pennsylvania. McGovern analyzes ancient fermentation vessels to determine what ancient cultures drank. His books on the topic combine archaeology, history and biology – a fascinating glimpse at yet another aspect of humanity’s rich relationship to a diverse earth.

McGovern is able to develop lists of ingredients of ancient brews. Fortunately, they aren’t relegated to the museum. He turned to Sam Calagione, founder and president of Dogfish Head Brewing, to develop modern interpretations of ancient ales. I’ve long followed Calagione and his self-described “off-centered” approach, whether through his beers, his popular television show or various articles.

I recently learned Calagione also has a connection to The Nature Conservancy. His wife Mariah serves on The Nature Conservancy in Delaware’s Board of Trustees. Dogfish Head sponsors an annual run, the Dogfish Dash, with proceeds benefit the Conservancy in Delaware. This year the Dash drew 2,500 runners from 26 states, and raised $100,000 for conservation.

I recently had the chance to talk to Calagione about the ancient ales, the role of nature in beer and the importance of conservation. Here are excerpts from Calagione.

Foraging for Beer

When I was researching to open a brewery, I wanted to try to do something very distinct, very inexpensively. I was a 24-year-old kid with a business plan, and I knew I wouldn’t be able to compete dollar-for-dollar with the first generation of great American craft breweries that opened in the late ‘80s, like Sam Adams and Sierra Nevada.

I thought, maybe I’ll try to create the brewery focused on bringing culinary ingredients from around the world into the beer-making process, instead of focusing on trying to replicate European beer styles.

And so right out of the gate, we were doing beers with pumpkin meat and apricots and maple syrup from my family farm, locally roasted coffee, vanilla beans, sort of foraging through the woods and fields of America for our ingredients.

And when I came out with these beers, in the mid ‘90s, honestly there was not a big audience for that.

Looking Back, Way Back

People weren’t so much as impressed with our culinary approach to brewing as they were alarmed and sometimes even pissed off that we were “screwing with modern traditions” of brewing by adding these culinary ingredients. So that got me researching the older history of brewing back to the time when pretty much every culture in every corner of the world made beers just by what was beautiful and what grew beneath the natural grounds they walked on.

I had started researching and bringing back to life many century-old recipes like Tej, a honey beer of Africa, and Braggot, the medieval British beer-fruit hybrids. So I was already on the path of historic beers.

But I was never able to tie it to actual archaeology and molecular archaeology until I met Dr. Pat McGovern and we started our first project together, which was the Midas Touch Project. Midas Touch is based on the ingredients found in 2,700-year-old drinking vessels in the tomb of King Midas. It’s somewhere between beer, wine and mead.

On Making Ancient Beverages to Modern Tastes

We start by trying to be as respectful and authentic as we can given what we know of these beers. In essence, Dr. McGovern can really only give us a laundry list of ingredients that he’s identified through his analysis of residue found in tombs and on crockery around the world from these thousands of years-old tombs.

Then it’s up to us as modern brewers to convert that laundry list of ingredients into a practical modern beer recipe.

Then we have to decide what ratio each ingredient might have been in. Was it carbonated? Was it filtered? How much alcohol did it have? So as modern brewers, we get to put our thumbprint on this moment in history when we’re brewing these liquid time capsules and bringing them back to life.

The Biggest Difference? Knowledge of Microbes.

In general, the biggest liberty we take with ancient ales is that we do most of these with one single pure brewer’s yeast strain. We use different ones, or we’ll use a wine strain like we did with the Italian ancient beer called Birra Etrusca. But in general, we use a pure yeast strain where, in reality, all these ancient cultures, when they were brewing – they didn’t even know yeast existed.

These recipes came from a pre-Louis Pasteur understanding of the production environment. Inevitably, all these ancient beers probably tasted very much like modern lambics, with a very sour and acidic taste from wild yeast and bacteria that people didn’t understand.

Chicha, the Beer that Requires Human Saliva to Brew

Chicha is really just a generic term for corn-based beer from Central or South America. There’s a tradition of people chewing on these corncakes, letting them sit overnight, so the enzymes in our saliva do the work of converting the starch in those corncakes into fermentable sugars.

You plop the corncakes in with hot water, and you make a mash and make a beer from it.

The beer we made with Peruvian blue corn and strawberries and tree seeds actually turned out really good. It sold very fast, but it was polarizing, not because of the way it tasted, but just because we want to be transparent with our production process.

We told them that a catalyst for this brew is human saliva. Even though we also tell them we boil it after we chew on it, so it’s sterile, some people were still a little weirded out by that production method, for sure.

Connecting Beer and Conservation

As a startup company, your number one goal is to stay in business without going bankrupt. But within a few years, we had some financial strength, and we immediately recognized the obligation to give back to the communities that give our company its sustenance and its ability to succeed and thrive.

My wife Mariah, who runs the company with me, and I, set the goal of identifying communities that made sense for Dogfish to get involved with. Since we make our livelihood off these creative recipes that are all made from natural ingredients, things that grow in the earth, it made perfect sense for us to prioritize working with The Nature Conservancy, whose mission is protecting natural spaces around this earth.

The Dogfish Dash

The Dogfish Dash was really my wife Mariah’s child. We started in 2007, and we’ve raised almost $500,000 for The Nature Conservancy in Delaware. My wife Mariah whose on the board, and Mark Carter, who runs the non-profit part of our company, are very involved in working with The Nature Conservancy. The Dash is a fun way for people to contribute, have a fun run and invest in our natural community.

Protecting wild lands in many cases protects the ingredients that go into our beers. The Dogfish Dash dollars have gone to improving the McCabe Nature Preserve, which is right in Milton, Delaware. They’re doing trail work and wildflower meadows. There’s an awesome future project with a canoe and kayak dock on the Broadkill River.

On Sustainability

Sustainability efforts are a big part of Dogfish. We have an amazing water recovery plant where we generate 40 percent of our own power on site through recovered water. We’re incorporating skylights into our production spaces so we work in natural light environments. We have a robust recycling program. Really, we’re trying to be good stewards of the earth while also trying to be good stewards of the brand. Those things aren’t mutually exclusive.

The Diversity of Life, and the Diversity of Beer

The industrial era brought many challenges to the earth. We did not take as good care of the earth and our air and our waterways as we should have.

That same era brought homogenization of beer cultures around the world, to the point where a handful of international conglomerates collectively dumbed down beer to be this one monolithic, very low-flavored beer style called the light lager. So craft brewers in general and Dogfish Head specifically have been all about bringing back flavor, bringing back diversity to the commercial brewing landscape.

I think that’s similar in a way to The Nature Conservancy championing the diversity of life on this planet.

Join the Discussion