Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander viewers should use caution viewing this post, as it may contain mentions of deceased persons.

History is palpable at Parnngurr waterhole, even for one who has not lived it.

Martu elder Ngamaru Bidu sits quietly on a boulder next to me, a multicolored scarf shielding her head from the sun as we watch the scientists work in the shallows beneath the fig tree. Only later did I learn that she was taken from here. In November of 1963, government workers pulled up to this rockhole, gathered Ngamaru and her family into a truck, and drove them to Jigalong Mission.

After 20 years of absence, the Martu people returned to their land in the 1980s and continued cultural practices that care for the country and the desert ecosystem. Now, the Martu rangers are building a database of sacred waterholes and partnering with scientists to better understand the impact that feral camels might have on these water sources.

Martu, Past and Present

The Martu people are the traditional owners of this part of the Western Desert, which stretches across millions of hectares in west-central Western Australia. Their land forms part of the largest intact arid ecosystem on earth, covering more than 40 percent of the Australian continent. Today about 1,500 Martu live in four communities on country — Jigalong, Parnngurr, Punmu, Kunawarritji — and another 1,000 live elsewhere.

Aboriginal peoples have lived in Australia for at least 50,000 years — the longest continuous human culture surviving today. Anthropologists estimate that the Martu people have lived in the Western Desert for at least 5,000 years, living in small, nomadic groups.

Some Martu came into contact with westerners in the early 1900s, as pioneers attempted to build cattle-drive tracks through the desert, including the well-known Canning Stock Route. By mid-century many Martu had moved to pastoral stations and missions, but this desert is so vast and remote that some groups of Martu didn’t encounter westerners until the mid 1960s — including elders like Ngamaru.

Anthropologists estimate that there were more than 200 Martu still living as mobile foragers in the northern areas of the Western Desert at that time. Shortly after, any remaining Martu were removed from their land to make way for the British Government’s Blue Streak missile testing, for which Martu country was the designated crash site.

And so the desert was empty. For two decades the Martu were without their country, and the country was without the Martu.

Slowly, Martu began returning to country in the early 1980s. Several families established Parnngurr community in 1984 as the Martu fought against a proposed uranium mine nearby. The exact location for the community was chosen specifically because of the cultural importance of the nearby Parnngurr rockhole.

The sun slides farther down the rock wall above the waterhole. Spinifex pigeons splash their wings at the pool’s edge, while a flock of zebra finches tumbles down the rockface like an avalanche of pebbles.

We are here to install data loggers as part of a scientific study by The Nature Conservancy scientists and Kanyirninpa Jukurrpa (KJ) rangers to better understand how feral camels impact these waterholes and if camel management improves waterhole health.

Ngamaru is one of several Martu joining us today: Thelma Judson, Anthony Burton, and Carol Williams. Tina de Groot, a ranger coordinator for the Martu cultural organization Kanyirninpa Jukurrpa, mentions to us later that Carol’s grandmother, Daisy Craig Kadibil, was one of the three Martu girls that ran away from the Moore River Native Settlement, north of Perth, and followed the Rabbit Proof Fence 2,400 kilometres home to Jigalong on foot.

As the Martu returned to country, they began fighting for the rights to their land. And their knowledge of waterholes was key to their success.

“To successfully obtain Native Title you have to demonstrate a continuous connection to country over time,” says Tony Jupp, of The Nature Conservancy Australia. Even amongst Aboriginal peoples, the Martu are largely unique in having living elders who were born on country, before contact with westerners. “The fact that Martu elders still have memories and a mental map of their country and its water sources was critical,” says Jupp.

Finally, in 2002 the Australian government awarded the Martu rights to more than 13.67 million hectares of land. Encompassing an area about twice the size of the state of Alabama, it was the second largest Native Title Determination in Australian history.

Mapping Waterholes to Care for Country

As the Martu returned to country, they began reviving cultural practices that benefit both the Martu and the desert ecosystem. KJ is a nonprofit organization that helps Martu build sustainable communities, care for country with traditional ecological knowledge, and assists Martu keeping their culture strong. Much of KJ’s work on country is carried out by ranger teams from different communities, who monitor local fauna, conduct burns, manage non-native species, conduct return-to-country trips with adults and children, and care for waterholes.

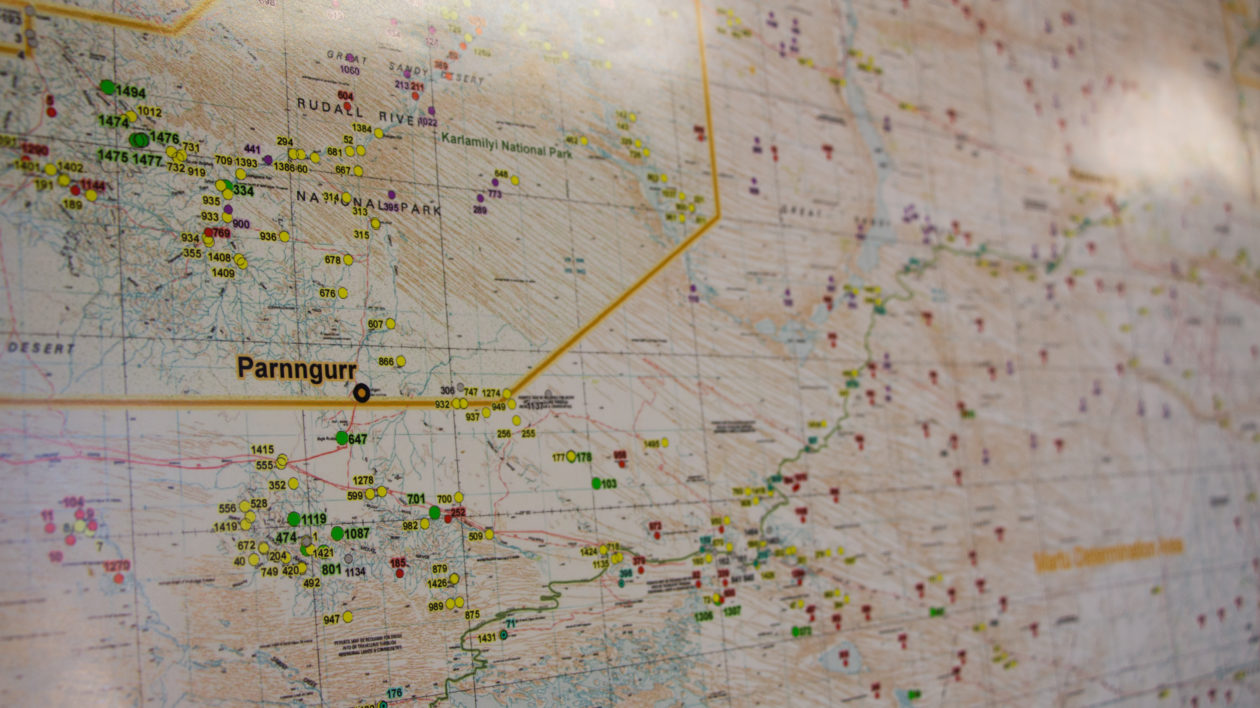

Waterholes are at the center of KJ’s work to preserve Martu cultural knowledge. During the fight for Native Title, the Martu created a map of all known waterholes on country and their local Martu names. Now, KJ and the Martu are translating that cultural knowledge into a digital database of more than 1,491 different water sources on country.

The most current map is pinned to the walls of KJ’s office in Parnngurr, where we planned our week of fieldwork. Multi-colored dots are scattered all across country — even beyond the borders of the Native Title determination — each coded with a number and a green, red, or yellow mark.

The de Groots explain the different stages: First, the Martu plotted the location and name of each waterhole onto an accurate map (red) and then KJ staff verified that location with other Martu (yellow). Next, the ranger teams ground-truth the location of each waterhole, often via helicopter, with the elder Martu.

“Once they get up in the helicopter, the elders start singing the song that follows their walking line that they would have used for water,” says de Groot. “The song refers to the land features, so it it takes them from one rockhole to the next.”

Only when the waterhole database has the Martu name, an accurate GPS location, and all of the cultural information does the waterhole change to green on the map. As of July, 37 percent of all waterholes have a GPS location documented.

“They’re trying to get as much information as possible before all of these old people pass away,” says de Groot. Not only does the waterhole mapping help preserve cultural knowledge, but it also helps pass that knowledge on to the younger generation and helps open up new areas of the country where Martu haven’t visited, sometimes for decades.

In an aim to improve waterhole health, a feral camels culling program is run each year with the support of the Conservancy, Parks and Wildlife and KJ. As of June 2015, KJ has helped cull more than 26,000 camels and 2,000 donkeys from Martu lands over six years. Another 1,000 camels were culled just one week before our team of scientists arrived.

The data loggers that Ngamaru and other Martu elders helped us install will help Conservancy scientists determine how detrimental camels are to waterholes in this region and if KJ’s camel management helps reduce those impacts.

A black-faced cuckoo-shrike hovers over the ridge, wings beating, and then plummets into the flock of finches twittering at the pool’s edge. As we watch the scientists positioning the data logger on the bottom of the pool, Thelma Judson leans towards me. “The kids still swim here in hot times,” she says, pointing to a narrow slide submerged in a corner of the pool.

The Martu have returned to country, and a new generation of children play in Parnngurr rockhole’s cold water.

This research was initiated as part of the Martu Living Deserts Project, funded by BHP Billiton, to conserve part of the world’s most intact desert.

Join the Discussion