I’m standing in the Aransas National Wildlife Refuge visitor’s center, and I’m nervous. I’ve spent the morning chasing the last wintering Whooping Cranes on the Texas coast with Jorge Brenner, the Conservancy’s associate director of marine science for Texas.

“There might be a few left,” the ranger said. “You might get lucky.”

In the field behind the thousand-year old live oak? No whoopers. The pastures on 8th street, where the local landowner puts out feeding bins? No whoopers, just Whistling Ducks. Goose Island State Park? A bemused yet nice park staffer, but no whoopers. Flyovers as we speed up Texas 35? Nope.

After nearly 100 miles and several hours chasing down the previous week’s eBird sightings, Aransas was our last chance. On the park map, the staffer drew a wide arc over Mustang Lake. “Two birds have their wintering territory here, but they might have left already.”

Chasing Migrants in Texas

The Gulf of Mexico is awash with migrants — at least 395 bird species are found over, in, or near the Gulf of Mexico and its coastal fringes, many of them passing through Texas on their annual migrations. Some are so driven by their migratory urge that they’re here for a mere day, others hopscotch their way up the coast over a few weeks.

And it’s not just birds — beyond the bay and barrier island to our left is the ocean, where migrations of similar magnitude occur beneath the waves. Bluefin tuna travel from the far western Atlantic spawn, manatees migrate from the sea to inland springs, and loggerhead and Kemp’s Ridley sea turtles nest on just a handful of Gulf beaches.

“Just like there are flyways above the surface for birds,” says Brenner, “there are blueways below the surface for marine life.”

Brenner and his colleagues at the Conservancy have spent two years mapping the diversity and movement of migratory species in the entire Gulf ecosystem. Their new analysis collates data on 26 species from more than 100 biologists and researchers from the U.S., Mexico, Canada, and Cuba — creating the most comprehensive data assembly and threat assessment for migratory Gulf species to date.

Their research aims to answer the critical question for wildlife conservation in the region: How can we protect species as diverse as warblers and whales, whose migratory pathways span thousands of miles through air and water, and some of those pathways are very poorly understood?

“For most people, the Gulf isn’t a place where dynamic migration happens all the time,” says Brenner. “But it happens constantly and it’s incredibly important.”

From Whoopers to Warblers — Avian Migration in the Gulf

Shortly after noon, Brenner and I walk quickly up the winding metal ramp to the Aransas National Wildlife Refuge observation tower, rising steadily into the canopy of a live oak grove. Overcast skies threaten rain, while raucous laughing gulls ride the building winds.

We begin scanning. The closest birds are hundreds of feet away. Small white smudge? White Ibis. Bigger white bird? Great Egret.

And then suddenly we see them — two large, white shapes moving slowly on the far shore of the lake. Even with gale-force winds and a quarter-mile between us, the cranes are unmistakable. Nothing else on this marsh moves the way they do, slowly strolling in perfect unison as they graze the marsh for blue crabs and fish.

Within minutes Jorge spies three more Whooping Cranes slowly working a field farther into the distance, their long, white forms nearly disappearing amid the shimmering heat haze.

“I was really nervous that we weren’t going to find them,” admits Brenner. Every one of the 300+ wild Texas whoopers migrates here for the winter, but most them are already winging their way northwards to their breeding ground in Alberta. “That is why this place is so important,” says Brenner. “They depend on the quality of this habitat for their very existence.”

Brenner explains that historically, whooping cranes were more distributed along the Texas coast, when their population numbered more than 10,000. But hunting, human disturbance, and habitat conversion caused the population to crash, and the remaining birds are squeezed into the refuge and surrounding patches of marsh.

These water-washed marshes and oak groves are critical for more than just cranes. The Gulf of Mexico is one of the most critically important geographic areas for bird migration in all of North America. But it’s also a massive barrier — 1.6 square kilometers of open ocean without a perch in sight.

Tiny, half-ounce warblers complete the trans-Gulf journey in a single flight, lasting 18 to 24 hours. The effort nearly kills them, and many birds without sufficient fat reserves or with the bad luck to encounter a storm don’t survive the crossing. Other species — like raptors, flycatchers, and swallows — take a more circumspect route, following the curving coastline from Texas into Mexico and on to Central America. Called the circum-Gulf route, this flyway is the most heavily used raptor migration corridor on earth.

The movement is nearly constant: north-bound hawks arrive as early as March, followed by shorebirds and warblers. Cranes and wintering ducks depart northward. July sees the first ospreys heading south for the winter, followed by the hawks and shorebirds. With the exception of a few quiet months in January and February, it’s a constant stream of movement into and out of the Gulf.

As part of their analysis, Brenner combined occurrence, satellite, and geolocator tracking data from nine species of Gulf migratory birds — Broad-winged Hawk, Osprey, Cerulean Warbler, Wood Thrush, Black Rail, Black Skimmer, Whooping Crane, Redhead, and Audubon’s Shearwater — to identify migratory corridors, areas of high movement density, occurrence hotspots, aggregations and stopovers for all bird species in the Gulf.

“By looking at the migrations of birds, we can infer what is happening beneath the surface,” says Brenner. “Marine migration is a similar process and it’s just as diverse as bird migration, if not more.”

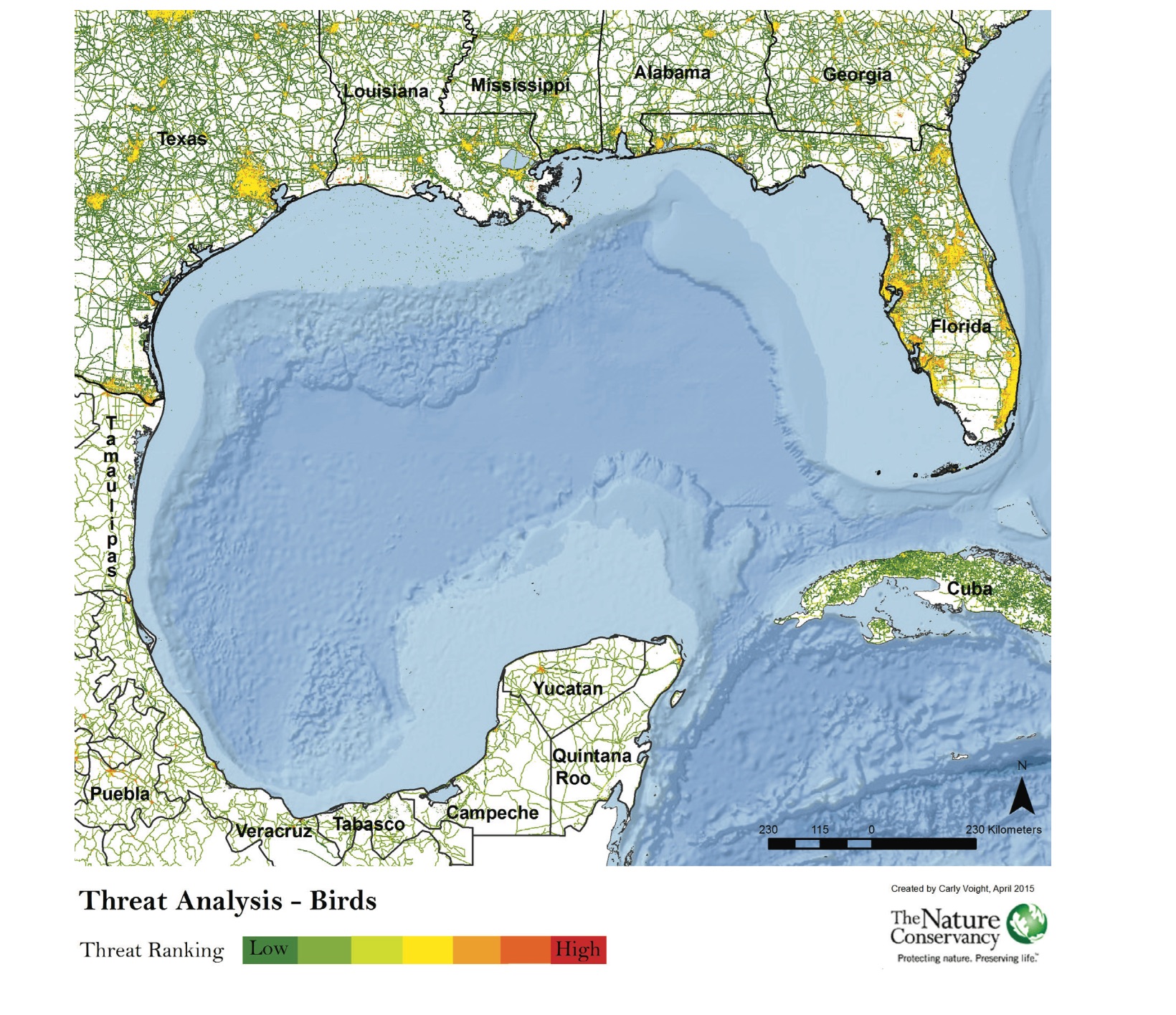

They then used that information to identify and weight nine threats to migratory birds: urban and suburban areas, wetland, mangrove, and forest loss, roads, tall structures, wind turbines, and electric lines. Four stand out: urban and suburban areas, as well as wetland and forest loss.

Urban and suburban areas both destroy or convert needed forest and wetland habitat and introduce dangerous obstacles, like buildings, vehicles, and powerlines. They also bring with them native and introduced bird predators, especially cats, which are the most significant source of anthropogenic bird mortality in the entire country.

Encouragingly, Brenner’s report shows that large blocks of key habitat do remain along the Gulf, especially along the coasts of Louisiana and south Texas. The areas most at risk are existing major urban areas, especially the Florida peninsula.

They also performed similar analyses for other taxa, identifying threats like bycatch coastal habitat loss for marine fish, dams for anadromous fish (those that migrate inland to spawn), vessel collisions for marine mammals, and longline fishing and beach-light pollution for sea turtles.

The Full Scope of Gulf Migration

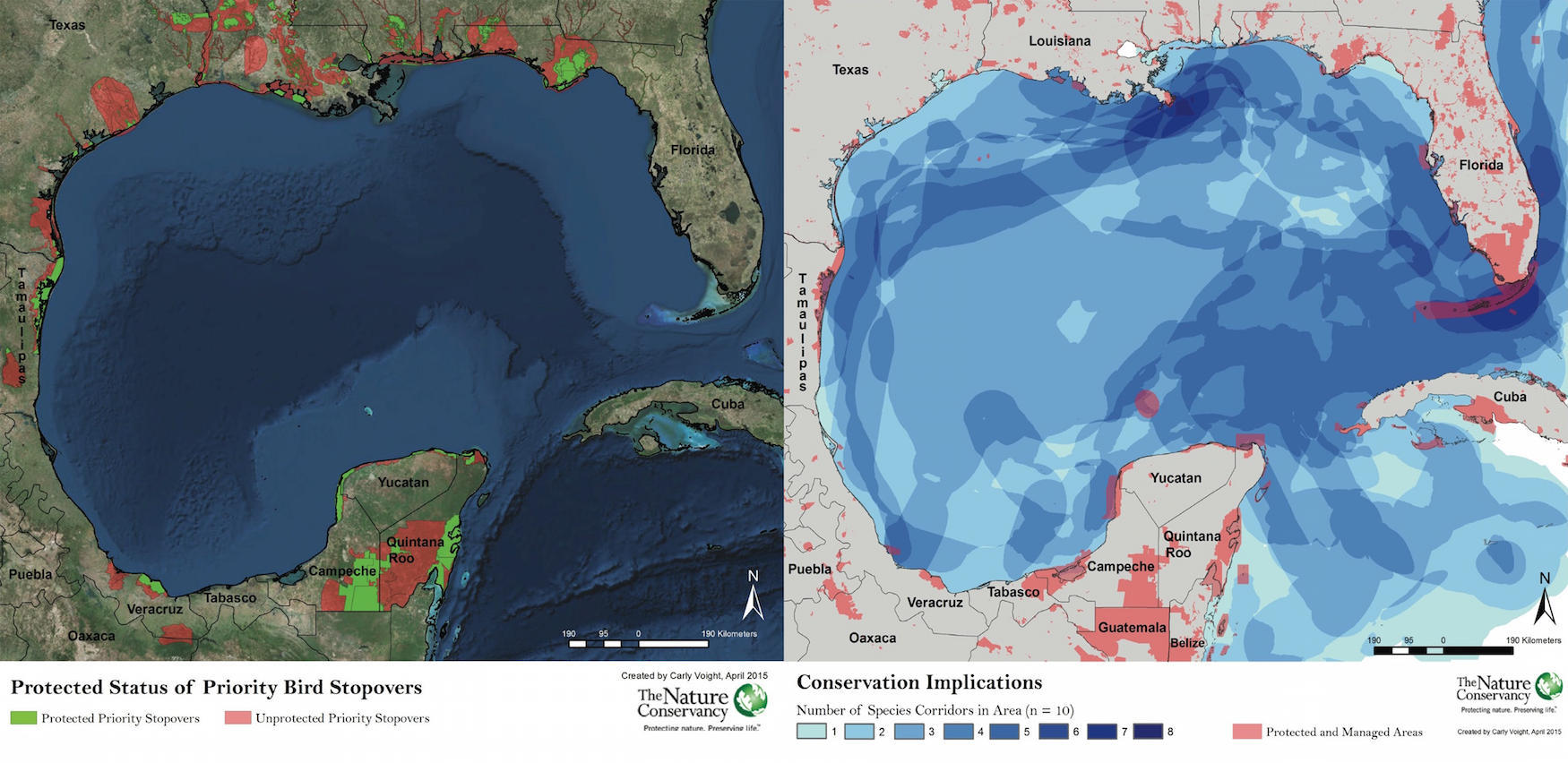

Brenner’s final stage of analysis was creating corridor and hotspot maps for all taxa.

Those maps revealed the Gulf’s most significant migratory blueways: the confluence of the Mississippi River and the Gulf, South Florida and the Florida Strait, the northern Yucatan Peninsula, and northwestern Cuba. By comparing the multi-species corridors against current protected areas in the Gulf, Brenner’s team found that more than 99 percent of the aquatic corridors and more than 80 percent of bird stopovers lack any type of protection.

Another significant finding of the report was just how little data is available for many Gulf species. Satellite tracking data is available for larger marine species that spend a significant amount of time at the ocean’s surface, but very limited for small fish and bird species.

Data were also biased towards species with recreational or commercial value, like fish, or endangered species, like turtles and marine mammals. Brenner also found a geographic limitation to data, with a majority of existing data focusing on the northern Gulf and United States, neglecting Mexico and Cuba. That lack of data is especially worrying given the international scale of Gulf migration.

“Our results show that efficient management of the migratory megafauna in the Gulf requires a transboundary approach,” says Brenner. “It’s a complex process beyond one single national jurisdiction that has multiple requirements in space but also in time.” He says that coordinated management between Gulf nations will be especially important given the limited resources available to conservation in all three nations.

Next, Brenner and his colleagues will undertake a second phase of analysis, incorporating more species to the pathway analysis, including other species of tuna and hawksbill sea turtle. They will also identify key areas needed by these species while migrating in the Gulf by conducting an optimization analysis of conservation goals, threats, and habitats. Finally, they will identify what habitats are most relevant to each species for their long-term viability.

Brenner hopes that this assessment will motivate decision-makers to manage migratory species in space and time, which will require effective conservation across multiple jurisdictions.

“Migration connects places and populations, and helps maintain the health of the whole Gulf ecosystem,” says Brenner. “And mapping the diversity of migration is the first step to helping protect it.”

The fact that we are seeing whooping cranes at all is a tribute to Ernie Kuijt who’s life work it was to save these birds from extinction.Rest In Peace Ernie knowing that the world can still enjoy your beloved whoopers.