Conservation today operates in a world of targets: Protect 17 percent of terrestrial systems and 10 percent of marine systems by 2020; keep global climate change below 1.5 degrees Celsius by 2100; halve the rate of natural habitat loss.

But despite widespread adoption of protected area targets, wilderness areas are still declining rapidly across the globe. Now, new research shows that 9.6 percent of all global wilderness has disappeared in the last 20 years.

Large, Intact, and Endangered

Wilderness. It’s a loaded term, and one that means different things in different contexts. But all definitions share the common link that wilderness areas are large, biologically and ecologically intact landscapes that are free from human disturbance. Place like like Canada’s vast boreal forests or Australia’s red deserts. These areas are not entirely without people — many are home to indigenous communities — but they are free from large scale disturbance like industrial activities, infrastructure, and commercial agriculture.

Because they are large, intact systems, wilderness offers significant benefits beyond the existence value of natural spaces. Research shows that wilderness areas are more resilient to climate change, sequester twice as much carbon as degraded landscapes, act as species refugia, and help stabilize local weather patterns.

But how much wilderness remains on earth, and how well are we protecting it?

Mapping the World’s Wilderness

To answer these questions, James Watson, based at the University of Queensland and director of science and research at the Wildlife Conservation Society, set out to measure how the world’s wilderness has changed in the past two decades.

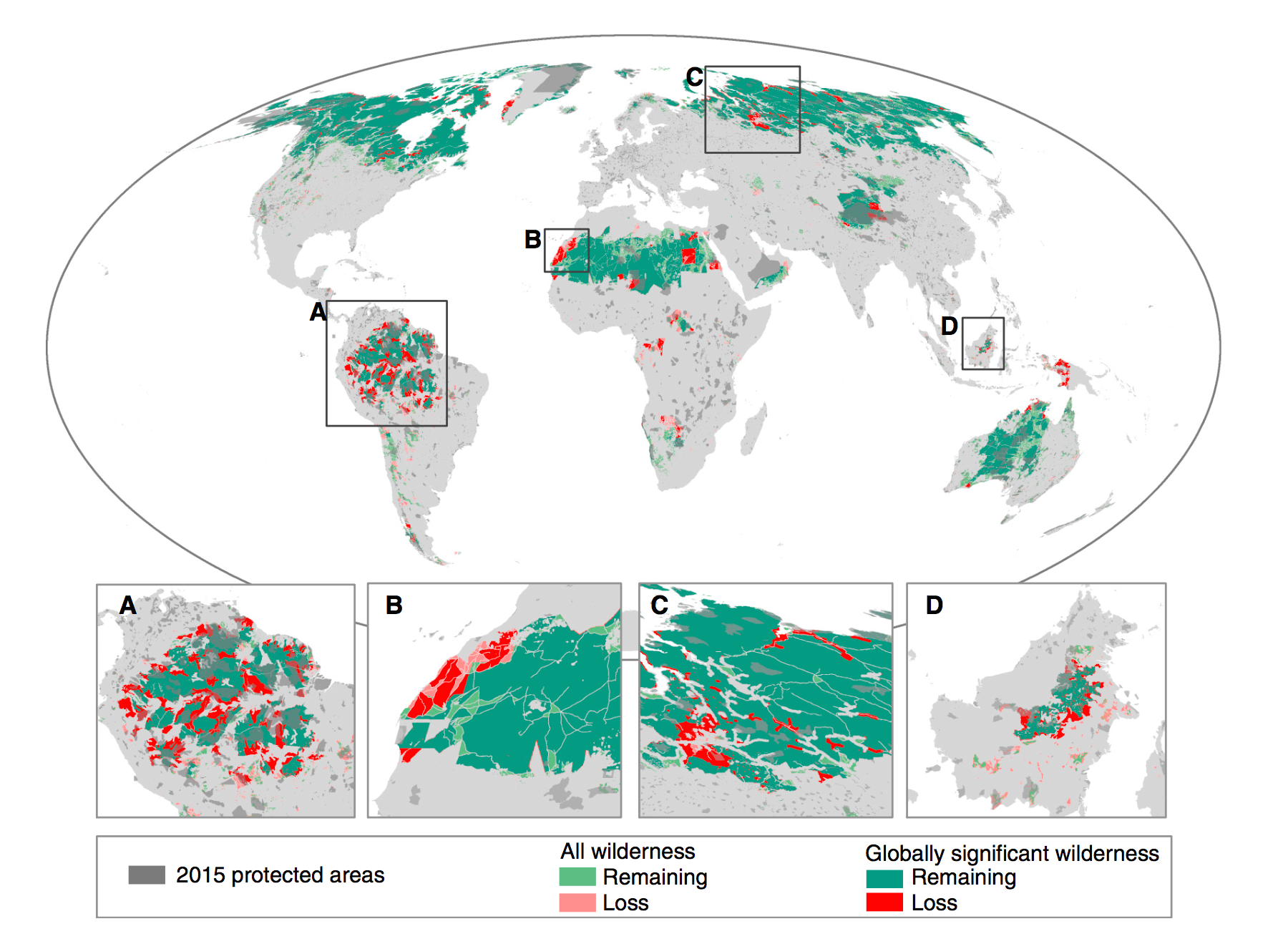

Watson and his colleagues first revised a map of the global human footprint, incorporating other sources of non-satellite data like roads and pasturelands, to identify where natural systems are under pressure from human activities.

“Then we reversed the map, focusing in on the areas where there is little or no presence of humanity” says Watson. The researchers then used Google Earth to ground-truth their analysis, examining 3,000 points across the globe to confirm that they had accurately mapped a presence or absence of human activity.

Their results, published recently in Current Biology, show massive declines in the world’s wilderness over the past two decades. A staggering 9.6 percent of global wilderness — 3.3 million square kilometers — has been lost since the early 1990s. South America and Africa are particularly hard hit, with 29.6 percent loss in the Amazon region and 14 percent loss in Central Africa.

“It’s catastrophic,” says Watson. “That’s an area twice the size of Alaska lost in 20 years.”

Just 23.2 percent of terrestrial land is still wilderness, but thankfully what does remain is largely intact. Watson’s analysis shows that of these remaining wilderness areas, 82.3 percent are large contiguous areas of at least 10,000 square kilometers. The majority of remaining wilderness is concentrated in the boreal forests of North America and Asia, arid Australia, northern Africa, and central Asia.

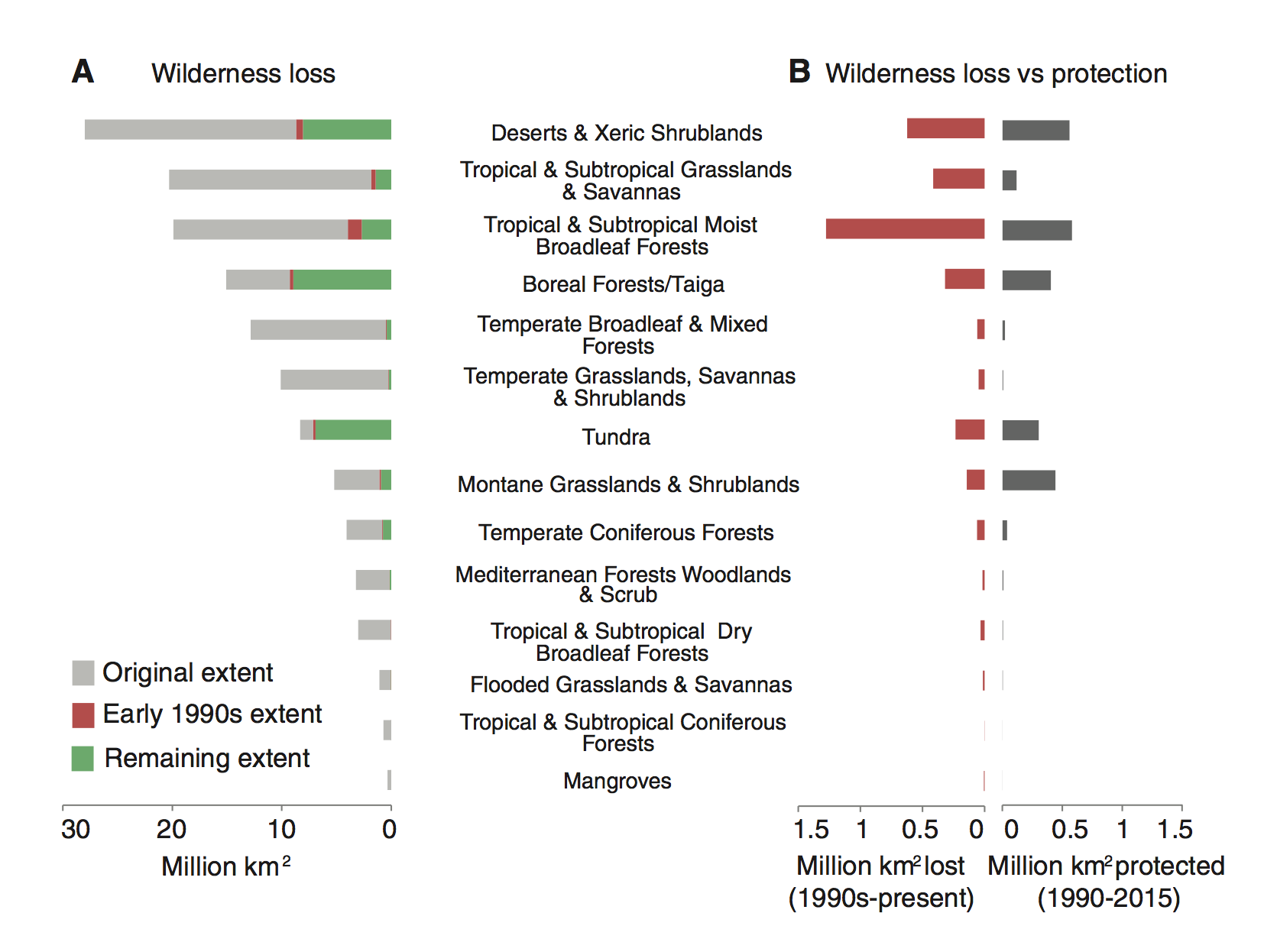

Both losses and remaining wilderness are not spread evenly across the world’s ecosystems. Of the 14 earth biomes, three have no globally significant wilderness areas left at all, and another five biomes have less than 10 percent.

These results come shortly after a new analysis of the global human footprint, published last month in Nature Communications. Researchers mapped changes in the the terrestrial human footprint 1993 to 2009, finding that 75 percent of the globe’s land surface is experiencing measurable human pressures. But they also found that while the human footprint is increasing — 9 percent over the study period — it’s growing slower than both population and economic growth.

Protecting Wilderness in an Era of Conservation Targets

The conservation dialogue is dominated by goals for protected areas, from the Aichi Biodiversity Targets to the Paris Climate Agreement, all of which are designed to increase protected land. But Watson’s analysis clearly shows that these targets don’t do enough to safeguard wilderness — his results show that in the last 20 years 2.5 million km2 of wilderness area was protected, but 3.3 million km2 was lost.

“We’re obsessed with percentages,” says Watson, “but we need to start focusing on the quality of protected areas, not the quantity.”

Good quantitative metrics help focus our attention on the quality of protected areas over the quantity. What are those measures? One would be the length or wilderness corridors. For example, if the Nature Conservancy purchased a long, narrow stretch of Siberian wilderness, it might confer more protection than the same area shaped in a square. An even higher cost-benefit might be something resembling a web or patchwork.

Is a global map available for Nature Conservancy owned (or protected) areas? If that map data is available for download, volunteers could create visualizations that illustrate longest corridor, and come up with other quality metrics to analyze and display.

Sobering, and wonderfully informative article, Justine. Thank you.