No matter where you live, there’s a good chance there is a crow nearby. What you might not notice is the family drama going on all around you. Many crows, especially during nesting season, live in family groups.

Mated pairs share territories with their grown children. The older offspring in turn help their parents with raising each season’s new brood of young birds.

This type of family life may not happen among all crow species or in all places. For example, in North America, we know that American crows and Northwestern crows cooperatively breed, but there is no evidence yet that fish crows pursue this lifestyle.

Lawrence Kilham was among the first to describe cooperative nesting in American crows in the early 1980s. Kilham was an avocational ornithologist, starting his studies in middle age amidst a career as a virologist. His approach to studying bird behavior was intentionally simple – observe individual behavior as much as possible.

For his crow studies, he worked seven days a week from a lawn chair with a notebook and binoculars. He lucked into finding a tame population of crows in Florida that were regularly fed by the owner of a private ranch. He was able to sort out individual crows based on their behavior and plumage idiosyncrasies.

Using this approach, Kilham completed a series of studies on crows and ravens that are summarized in his book The American Crow and Common Raven. Ultimately Kilham published more than 90 scientific articles that yielded many new insights into bird behavior.

As observed by Kilham, the Florida ranch crows worked cooperatively on all parts of the nesting process.

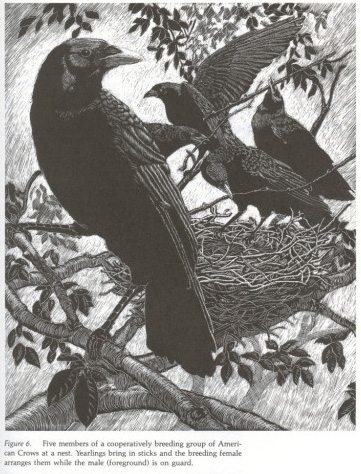

Helpers would bring sticks and other nesting material to help the female build the nest. At one nest there were five helper crows busily bringing sticks “faster than the one female could handle them.” The project quickly became a disorganized mess.

Eventually, the female somehow communicated that it was time to halt stick deliveries. It took her an additional two weeks to finally complete the nest with the materials on hand.

Kilham concluded, “There is a limit, conceivably, to the number of adult auxiliaries that can be of help rather than a hindrance.” In other words, too many cooks in the kitchen … Yes, crows have this problem, too.

Throughout the incubation period, the female spends 90% of her time incubating. She is fed by her mate and the rest of the helpers a few times per hour.

Kilham noted that the visit rate of helpers at hatching time was very high, but they weren’t bringing any food. He noted that “it seems that many of the visits were made out of curiosity” and ”the female moved aside each time a helper came, giving it a chance to look at the young.”

From then on the real work began for the family, with parents and “helper crows” making more than 20 visits per hour to feed the nestlings. The young birds continued to be fed exclusively by older crows for at least two weeks after they left the nest.

Subsequent long-term crow studies in New York led by Kevin McGowan of Cornell showed that pairs, like those that Kilham had studied in Florida, had year-round territories with young that stayed with their parents for up to six years. No crow bred on its own until it was at least two years old. The biggest crow family they recorded was 15 birds.

Why do crows stay at home to help rather than go out on their own?

Our greatest insights into this question come from a research team working in Europe with carrion crows. They have executed a series of studies focused on determining where and when it is beneficial to be a helper.

The team noted that in Switzerland cooperative breeding was rare, while in Spain it was common. To learn whether nature (genetics) or nurture (the environment) was driving cooperative nesting and family living, they experimented by moving Swiss crow eggs into Spanish crow nests.

The results? Nurture all the way.

The Swiss crows raised by Spanish parents adopted the local lifestyle of family living, while their brothers and sisters back in Switzerland left the home territory shortly after reaching independence.

The researchers presented two possible explanations for the difference between the two study sites.

The first hypothesis was that in Spain, there might not be enough territories to go around (in other words, it’s a tough job market), so the grown kids live at home for a while longer until something opens up.

Although the “tough job market” explanation is tempting, it turns out that Spain actually has more vacant territories available than Switzerland does.

The second hypothesis was that there may be a difference in food availability between the two sites that influences a territory’s capacity to support a family.

This hypothesis was proven to be correct. A key behavioral difference between Switzerland and Spain is that Spanish crows stay on territories year-round, while in Switzerland (and in an Italian study site), crows abandon their territories after nesting season. This is probably because they need to go beyond the territory boundaries to meet their food needs during the colder parts of the year. Families are then prompted to split up and, by the next spring, last year’s offspring are no longer around to help.

Even in Spain, where year-round territoriality is common, food availability is an important factor in determining whether the young stay or go. Experiments that added extra food to some territories demonstrated that last year’s young are more likely to stick around if there is more food.

Sticking around does imply a tradeoff. Surely all young crows aspire to have a place of their own some day. But in the meantime, a good part of their genes are being passed on by helping to raise their younger brothers and sisters. We would expect that their experience as helpers might make these young crows more successful breeders once they do get out on their own.

Cooperative breeding is common enough for us to know that it is beneficial under certain situations. About 40% of the 116 species in the crow family (including jays, magpies and nutcrackers) are cooperative breeders. It’s estimated that across all bird species, only about 9% are cooperative breeders.

Whether you’re referring to a crow couple or a human couple, it’s safe to say, it takes a village.

Thank you for this article. Very interesting and I loved seeing photos of the artwork with crows. We have been blessed with the same family of crows visiting every summer for 4 or 5 years now. Maybe longer. We’ve gotten to see the babies being fed on the ground, as well as being weaned. They also play!! I had no idea until watching the one crow stepping on a siblings tail. The crow that was being teased would drop on its back and kick its legs then hop up again. Lol Cutest thing! Will have to find out which type of crows they are that come here to Alberta Canada. 🙂