One of the most satisfying aspects of birding can be learning to identify the songs and calls of different bird species. Beyond identifying bird species by song, there is a deeper level of understanding that you can achieve. This is to actually understand what the birds are saying.

I had a fleeting moment of bird language comprehension during a research project on willets. I spent many hours over the course of a nesting season immersed in salt marsh sounds, eavesdropping on the daily discourse of willets and other birds using the study site.

One day I was making my rounds and heard a willet cry out. Typically a call of this sort sounded to me like some version of “MEEP!”

But on this occasion, my subconscious mind translated it to… “EAGLE!”

I looked up and there it was, a bald eagle. In an instant the bird life of the marsh erupted into the sky. Somehow it sunk in. The willet word for eagle had worked its way into my subconscious mind.

It stands to reason that if I could comprehend the call of a willet, all the other birds on the marsh could understand it as well.

Especially because their lives may depend on both understanding the alarm and reacting quickly to get out of harm’s way.

For each potential predator, birds must make a specific evasive response. When threatened by an eagle, the safest place to be is in the air.

I suspect that the willets have a word for peregrine falcon as well (a “high pitched jittery squeal” according one author), because the evasion strategy they must instantly implement to save themselves from a peregrine is different from their eagle response.

(To evade peregrines, the move is stay down and get low. Taking to the air is the worst place to be when these aerial hunters are on the scene.)

Why Birds Get to the Point

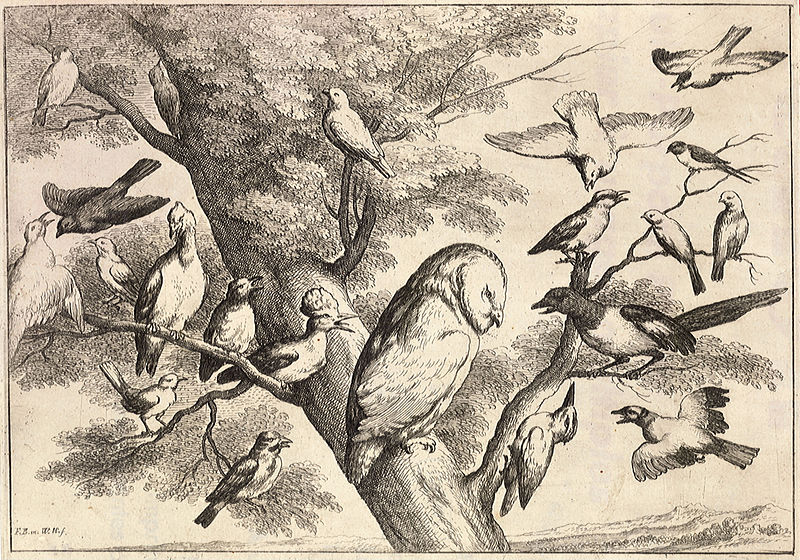

While birds may not have a huge vocabulary, they can (and must) quickly communicate information to each other. The best-known examples of birds and other animals’ ability to communicate the presence of predators.

A rich body of research has revealed that birds can communicate the presence, type and threat level of predators to each other.

Related studies have even shown that different species mutually understand the meaning of each other’s calls.

Experiments where chickadees and titmice are shown stuffed hawks and owls demonstrated that the birds tailor their alarm calls to the predator species and the threat it poses to them.

They save their fiercest invective (i.e. longer periods of calling with more protracted call sequences) for the smaller bird-hunting raptors like screech owls and sharp-shinned hawks. They are less concerned with big, less maneuverable raptors such as red-tailed hawks.

Whether its chickadees or titmice, each species is fluent in the other’s alarm calls, as further experiments have demonstrated. Red-breasted nuthatches, which often are part of mixed-species flocks with chickadees, also understand and react appropriately to the alarm calls given by chickadees.

Becoming Fluent in Bird Alarm Calls

Throughout the world, species living together have learned each other’s predator alarm language.

Chameleons in Madagascar scuttle for cover when a paradise flycatcher yells “hawk!”

In Kenya, dik diks (small antelopes) scram when a go-away bird gives warning.

Also in Kenya, vervet monkeys have their own calls for “leopard” and “hawk” but respond with evasive action to similar warnings made by superb starlings.

Woodchucks in Maine come to alert when they hear either chipmunk or crow alarm calls.

Red squirrels in Germany take flight when they hear the alarm calls of Eurasian jays.

…and the examples go on. The research so far makes it clear that verbal communication among animals about predation threat is very common.

Learning the fundamentals of these calls can enrich our own awareness of the natural world. If we can be tuned to these alarm calls we can allow the birds around us to point out creatures we might not otherwise notice.

The first step on the journey to understanding is to listen for mobbing calls. Often when a predator is identified by birds, they make a commotion. Soon other nearby birds join in and chorus of alarm calls is directed at the threatening entity. It is believed that mobbing functions to harass the potential predator in order to reduce its element of surprise and to drive it from the area.

In my own backyard I’ve witnessed these mobbing responses to predators. Once I saw my backyard chickadees accompanied by flock of five species of warblers bouncing around a snake coiled in a bush.

On another occasion the urgent alarm calls of robins eventually revealing the presence of cat in some undergrowth not far from their nest.

These sightings were made while I was in the middle of something else, but hearing alarm calls attracted my attention. It often takes awhile to discover exactly what the birds are responding to, but patient observation will usually reveal the interloper.

The best place to start learning about bird language is the book What the Robin Knows. The author, Jon Young, has spent a lifetime tuning into the subtleties of bird language gaining insights that may in some cases, put him a step ahead of scientists.

Young emphasizes the importance of spending a lot of time in one place, a “sit spot” listening to the rhythm of bird sounds. He recommends a daily practice and a level of deep concentration almost akin to meditation.

At a certain point in this practice the observer can detect and decode the various deviations of bird calls and behavior from baseline levels.

Although dedication to Jon Young’s methods can yield the almost magical power of divining the presence of other animals by listening to birds, anyone can quickly learn to notice the alarm calls of their backyard bird species.

These audio recordings at Young’s website are a great place to start learning alarm calls – adding a new dimension to your birding and backyard nature adventures.

I’m curious, is there a warning call birds give that would cause other birds to stay away or go away from an area? The reason why I ask is for a possible way to alert birds of a window for window collisions ( like a warning call with the window as the predator)…this way the birds could avoid going where the window is and not be harmed… but I don’t know enough to know if that might work as a solution

I have a barred owl in my backyard I have very small dogs and feed my song birds. Should I stop feeding my birds? The robins usually alert me when they are clise(we have a pair). Why do the robins alert me but the other birds don’t? I just want them to leave.

I’m used to the Chickadees scolding me whenever I exit my house. One day last summer, I was walking from my house to my garage when the Chickadee calls behind me became much more frantic. I turned around so see what had them so riled up and saw a Sharp-Shinned Hawk flying right at me!

Another time, I witnessed 30-40 Blue Jays mobbing a small hawk – either a Sharpie or a Cooper’s. It was intense as the hawk and jays flew in and out among the Sumac and more jays than I’ve ever seen in one place came flying over from the nearby woods to join in, screaming all the while.

Twenty plus years ago, a pair of red-masked conures came down our chimney: Ash & Cinder. These conures are native to Central America, and we have heard were let loose in the Bay Area (northern California) because they were not quiet pets: very true. This species of conures squawk, they don’t talk like some more melodious pet birds. Ash (the male) died many years ago, but Cinder continues to live in our home (with our six indoor cats). Her cage is placed near the backyard window every morning and she typically sits on top or in it watching the outside. However, not all her squawks are the same. Over the years, we have learned her “hawk” call. It is very distinctive and always if we look outside (in time) we see a Cooper’s hawk (typically) in our maple tree. She alerts the birds outside in case they missed it, we assume. As birder myself, I’ve heard the different calls from the same bird, and this article provided more details for me to watch for!

Another good place to learn about bird communication is in my book “The Language of Crows,” which makes all of the above points and even includes a CD of crow vocalizations and their meanings – one cut is of a crow, a blue jay, and a squirrel all giving their alarm calls simultaneously. You can find information about the book at http://www.crows.net

ABSOLULEY BEAUTIFUL BIRDS AND STORIES

Very interesting article. Here in Central Florida I frequently see Short-tailed Hawks by listening to the Purple Martins. When Short-tailed Hawks are about the Martins have a very intense alarm call that is quite distinct. Until I made that connection, I rarely saw the Short-tails since they often blend into the kettles of black vultures soaring about. (especially the dark morphs blend in quite well.) During the Martin nesting season the STHA’s make frequent visits at fledging time and can be seen at least several times a day. When a Red-shouldered Hawk is in the vicinity, the martins usually don’t respond unless the hawk is very close to the martin house. When Coopers Hawks make attacks, there is an alarm call but it is shorter and doesn’t seem as intense as with the STHA.

Thanks for your insights.

James

Birds from different continents also understand each other’s alarm calls.

As I stood in my farm yard my So. American macaw gave an alarm call. My African geneas all flattened to the ground as well as my American chickens. I responded by looking at the sky over the hay field and saw a hawk flying in the distance. Birds are wonderful.