I can hear birds.

Above, left, right, and center — calls ricochet off the dense vegetation of the Papua New Guinea rainforest, seemingly coming from everywhere and nowhere at once. Every one of these birds is a lifer — and I haven’t seen a single one all morning.

Just as my confidence in my birding ability is about to shatter, I hear Tim Boucher muttering silently to himself in frustration as he thumbs through the 528-page thick Birds of New Guinea book. He can’t figure it out either.

“This is the hardest birding you’ll ever do,” he says, still peering at a picture of an Olive-backed Sunbird. Wait, we’re still calling this birding? I think he’s trying to be encouraging, but it’s not working.

Ten days later we emerged from the forest, with a few dozen new birds on my life list and a thorough introduction to the trials and travails of tropical birding. If you’ve birded in the rainforest before, you have my full permission to laugh at my misery.

For those who haven’t, let this serve as a guide.

This is the hardest birding you’ll ever do.

Timothy Boucher

Just because the tropics have heaps of birds doesn’t mean you’ll see them.

Are the tropics (and Papua New Guinea) birding nirvana? Yes. Are there heaps of birds here? Yes. Are you guaranteed to see heaps of birds? No.

Birds-of-paradise don’t fall out of the sky as cassowaries cavort around your feet. In 10 days Boucher and I saw 39 birds. For perspective, that’s poor day of birding around my home turf of Denver, Colorado.

Perhaps Papua New Guinea is a special case, or perhaps our situation wasn’t ideal — we were birding on the off hours during scientific fieldwork. No fancy lodge in the highlands, no well-known leks, and no scope.

Even the most well-equipt tropical birding hopefuls should be aware that wherever they go, the birds aren’t guaranteed. What is guaranteed is rugged terrain, humid weather, and fleeting sightings.

Near the end of one particularly long and grueling hike to search, unsuccessfully, for a Lesser Bird-of-Paradise, the bird in question was calling enthusiastically from the canopy. I asked Boucher what he thought the ratio of birds-of-paradise we saw to birds-of-paradise that saw us was. He did not reply.

But that’s okay. Hard-won birds are better, and every bird you see in the tropics will be hard won.

Think you’ve prepared enough? You haven’t.

My first day birding with Boucher made me nervous. He was flipping through the bird book with terrifying familiarity. I was gazing around the mountain rainforest, thoroughly overstimulated and totally overwhelmed.

I suddenly realized that I was woefully underprepared to be birding outside of North America. I tried to practice, I really did. With six-weeks notice for the trip, I quickly bought the New Guinea bird book and spent my diminishing free time studying.

The book alone was completely intimidating. It’s one thing to be unfamiliar with individual species — that’s to be expected when traveling to an entirely new region, let alone a new quadrant of the world.

But I was unfamiliar with entire families of birds. Megapodes? Cuckoo shrikes? Fruit doves? Sunbirds?

Things really went south when Boucher started playing bird calls on the plane ride from Brisbane to Port Moresby. “Listen to this!” he said, handing me one of his earplugs. The primordial cries were like nothing I’ve ever heard. “Do you know what it is?”

No Boucher, I don’t. I really don’t.

Needless to say, my off-hour preparation was not enough. Buy the book as soon as you buy your tickets, if not sooner. Study seriously, comparing the plates with images online. (Because no illustrator alive can capture what the birds look like hopping through the dark forest 50 meters away.)

Don’t neglect that other half of your birding radar: sound. Head to Xeno-Canto and listen repeatedly to the calls of the birds you’re most likely to hear.

And lastly, pack a laser pointer. Nothing is more helpful when you’re trying to show your birding companions that exact twig on the far side of the tall strangler fig where the honeyeater is perched… oh no it flew, sorry.

eBird can’t help you here, you’re on your own.

I never knew how reliant I was on eBird until I birded the Adelberts.

For the uninitiated, eBird is modern birding central. One of the best citizen-science collaborations to date, users enter checklists of the birds they’ve seen around the world. eBird tracks life lists and sightings for you to explore at will, while scientists can make use of your data to study birds, migration, etc.

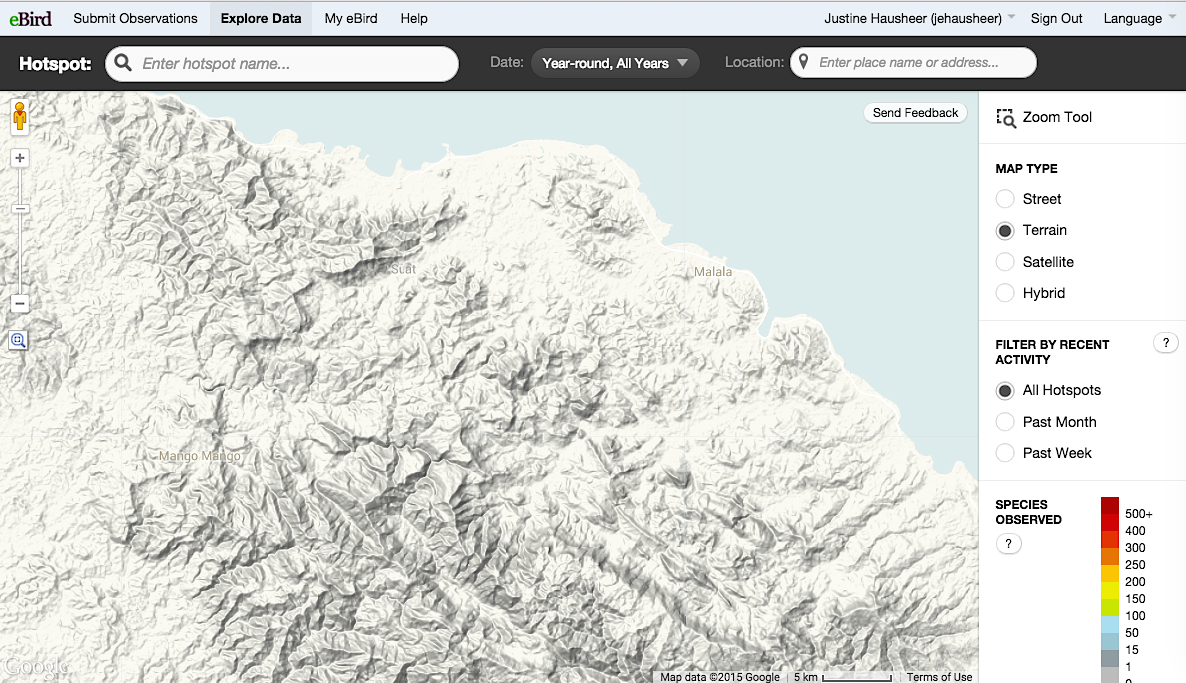

Before we left for the trip, I tried to look up a list of recent sightings for the Adelberts so I would know what to expect in the general time and place of my visit. Unfortunately for me, the eBird map looked like this:

Nothing. Literally nothing. This was going to be interesting.

It was the first time that I realized just how helpful it is to know what birds are expected during a given month, down to absurd specificity in highly birded locations. If I’m stuck between two species, that information usually tips me in favor of one or the other.

Not now.

So eBirders, take note… when birding off the beaten track in the tropics, you’re on your own. There is no cheat sheet. And that’s awesome. It will be a challenge for you and incredibly valuable data for eBird. You’re the first, and that’s worth and ensuing difficulties.

Tropical birding is not for sissies.

Be prepared to rough it.

If you want those birds badly enough you’ll need to put up with a lot: heat, sweat, innumerable insects, interesting rations, your own stench, constantly wet shoes, frustration, and some of the toughest terrain you’ll ever encounter.

I’ve already enumerated my advice for surviving scientific fieldwork in Papua New Guinea, and much of the same advice applies to birding expeditions. Including this additional bit of wisdom: waterproof binoculars.

Ask for help.

Responsible birders already know to hire local birding guides when traveling abroad. But if, like us, you find yourself birding on a non-birding adventure, ask the locals for help anyway. The villagers we stayed with in Musiamunat, Yavera, and Iwarame were absolutely delighted to show us birds they knew, if a bit bemused at our academic interest.

One morning in Yavera, we awoke to find that the locals had caught two birds for us in the middle of the night: a Hooded Monarch and an Azure Kingfisher, which the hunters found sleeping on a branch in the forest. Each bird had a string tied around its leg.

Appreciative but horrified, we quickly untied the strings and let the exhausted birds free. And then we thanked them. We were grateful to learn what they knew about the forest, and we wanted to convey to them that we valued their birds, but preferably alive and skittering about the jungle.

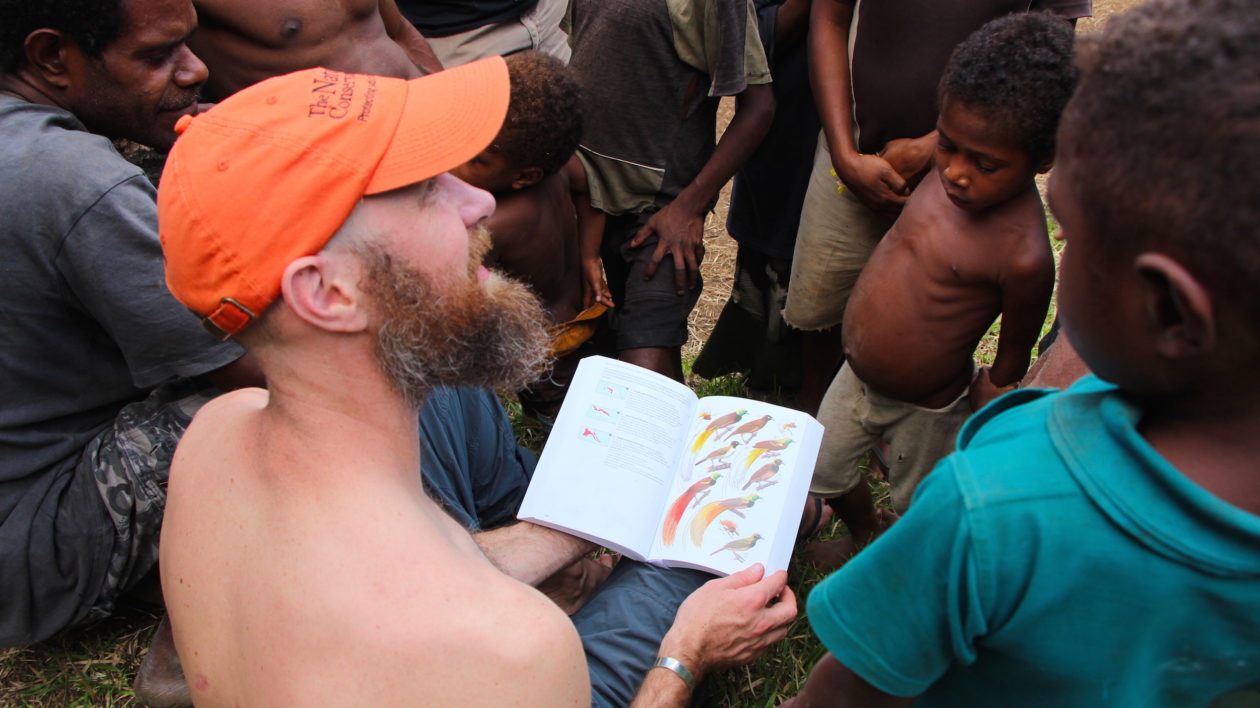

One of my most vivid birding memories from the trip was not watching a bird at all — it was watching my colleague show the children of Musiamunat my bird book. Wide-eyed kids looking on, the adults pointed to birds-of-paradise and cassowaries that they knew intimately.

The next day I caught a glimpse inside the Musiamunat schoolroom, where several posters hung on the walls. The only one I could see was the bird poster… on which were photos of a penguin and an ostrich.

I left my bird book behind.

One final piece of advice…

Get excited. You’re going to have a wicked good time.

How beautiful and sweet and tiny this Azure Kingfisher is… Poor birdy (but alive) :/

NYC. Rooftop /Water tanks. 10 in sight:/ but Birds go to only one of the 10 rooftop tanks on top of. 10apt buildings. Apart by 100 feet. Why birds go only to one. Of the ten building tanks???

No diff in temp of the selected tank vs. unselectrd