Your field guide is wrong. Many of North America’s birds are depicted incorrectly.

OK, maybe that’s not quite right: your field guide would look wrong to a bird.

If a bird paged through your field guide, it would wonder at how drab and dull the paintings look and would be puzzled at why the sexes are depicted alike in so many species when there are clear differences.

Birds see the world differently than us. They see a whole range of colors that we can’t see – colors that are literally unimaginable to us.

As a result of the vision differences between birds and people, we are missing stuff.

Some of what we are missing was revealed in a 2007 study that reported a color analysis of the 166 North American songbird species whose sexes look alike. They used a spectrophotometer to measure color of male and female bird plumage across the full range of colors that birds can perceive.

The findings were stunning. For the most part, these look-alikes only look alike to us.

A full 92 percent of the species depicted as having look-alike sexes in your field guide actually have distinct plumage color differences.

A sampling of our more common look-alike species includes red-eyed vireo, blue jay, American crow, tufted titmouse, black-capped chickadee, brown creeper, Carolina wren, wood thrush, mockingbird, and cedar waxwing.

Males and females of all of these species have distinct, measurable plumage differences that we simply cannot see.

Why can’t we see these differences? The answer is simple: birds’ heightened vision can discern a range of colors that we cannot perceive.

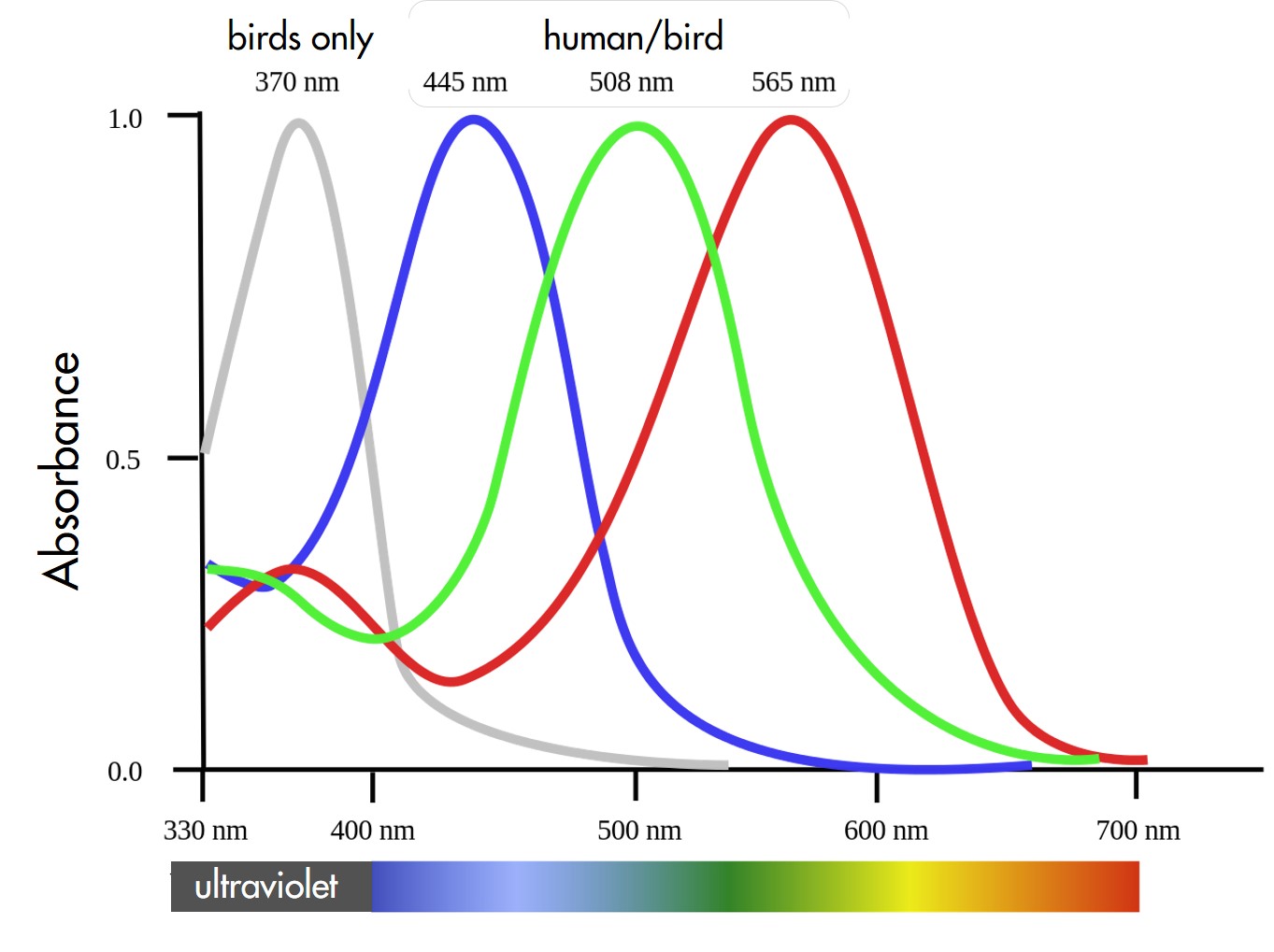

A bird possesses two advantages over a human when it comes to vision. First, birds have colored retinal filters made of oil that allow for an increase in the number of colors they can discern across the rainbow compared to us.

Second, birds can see colors in the ultraviolet range beyond the rainbow we see because many species possess a fourth type of color receptor. We share the other three color receptors with birds: red, yellow and blue.

The tricky part of all of this is that it is difficult for us to imagine what we are missing.

The color palette of birds is simply broader. You know that yellow and blue make green, and that red and yellow make orange. But what does yellow and ultraviolet make when they are blended together?

It makes something unimaginable.

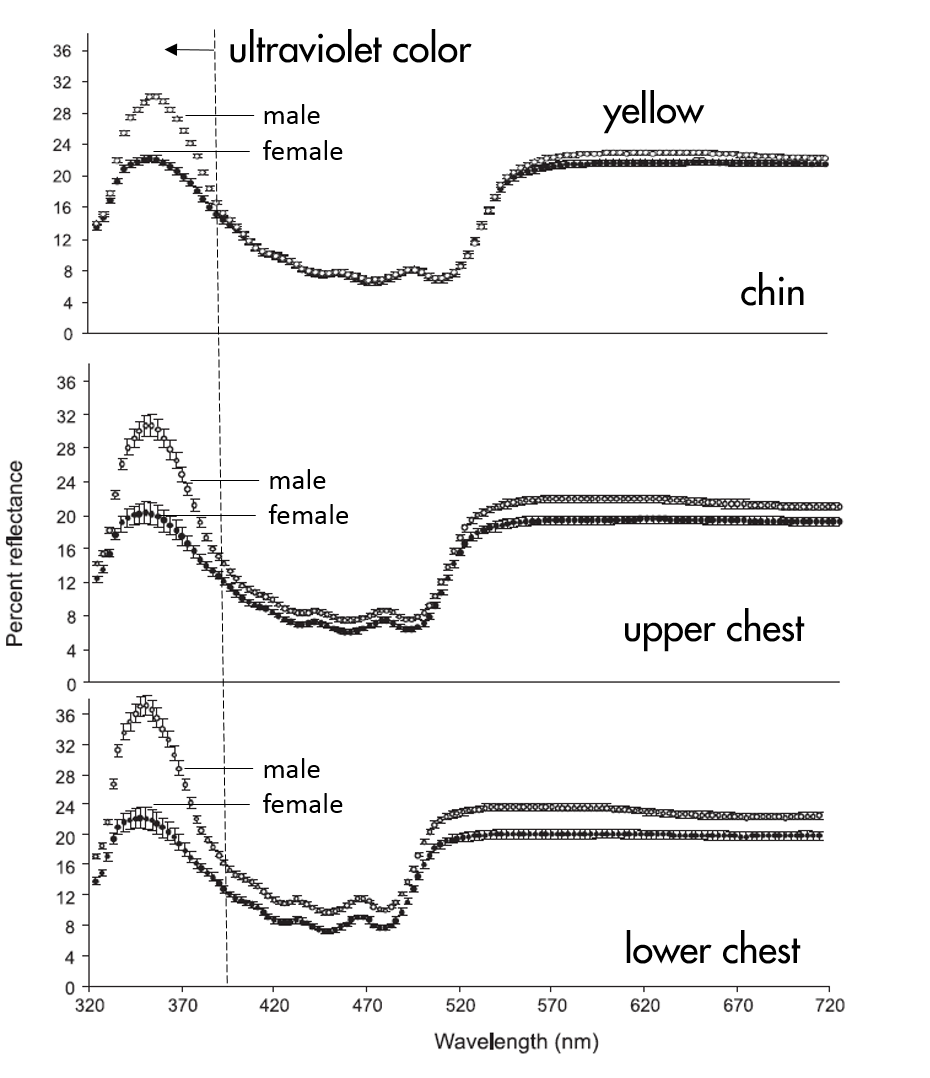

But that’s just what’s on a male yellow-breasted chat’s chest: a blend of yellow and an unimaginable ultraviolet shade beyond our perception.

The Ultraviolet Yellow-Breasted Chat

Chats were the focus of an experimental study which demonstrated that these birds are seeing and reacting to invisible (to us) color differences.

Researchers presented wild chats of known sex with a taxidermied male and female chat. The researchers made these introductions during nesting season, when birds are territorial and courting mates.

To us, the male and female stuffed chats would look the same. But the wild birds behaved in a sexually appropriate manner toward the stuffed birds.

The territorial male chats attacked the stuffed male in attempt to eject the intruder – and they attempted to court the female stuffed chat. Female wild chats gave an expectedly more tepid response, but when they behaved aggressively, their aggression was directed only at the stuffed female.

This was proof that the chats are seeing something that we can’t.

Beyond look-alike sexes, in parts of the world there are look-alike species. One example of this is the mountain tanagers of the Andes in South America.

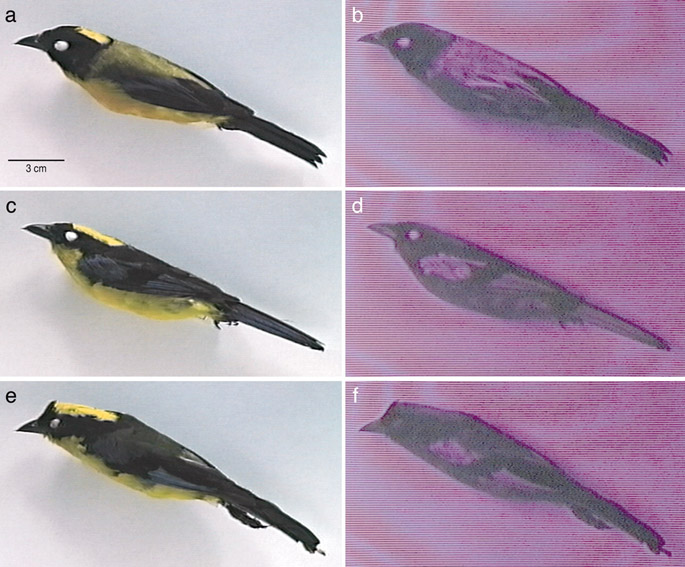

There are two species that look nearly identical, but when UV colors are taken into account, their markings are strikingly different. One species has a back that lights up with UV color, while the other sports UV shoulder patches instead.

The photo below also illustrates these differences. The upper bird is the black-chinned mountain tanager. The second one down is the black-backed subspecies of the blue-winged mountain tanager and the lowest is the olive-backed subspecies of the blue-winged.

The top and bottom birds look very similar to each other in the wild, but the UV reflectance images show big plumage differences — the top bir’ds back lights up with UV color.

These studies reveal that we are only seeing a dim representation of what birds really look like.

Our senses are tuned to specific frequencies to the exclusion of others. There are frequencies that are too low or high for us to hear and wave lengths of light that we aren’t able to see.

Other animals have different tunings. We know that a “dog whistle” is too high pitched for us to hear, but our dogs can hear them just fine. And we know that dog has a much better sense of smell than we do.

But we do surpass dogs in the color vision department. Dogs only have two color receptors: blue and yellow. Comparisons between our vision and dog vision gives us a way to conceptualize what we are missing regarding bird vision.

It is easier to imagine (and visualize) one less color receptor than it is to imagine an additional color receptor.

[cgs-juxtapose first_attachment_id=”48367″ second_attachment_id=”48366″]

Seeing what dogs are missing with one less photo receptor gives us a sense of what we too are missing with one less photoreceptor.

Awareness of our sensory shortcomings compared with birds is a striking reminder that there are phenomena all around us that we cannot detect with our senses.

As birders, we must accept that as beautiful as birds appear to us, we will never be able to behold their true colors. We are left only to revel in the known unknowns and wonder about the unknown unknowns yet to be discovered in the invisible world around us.

Photo collage credits: Wood thrush by billtacular; crow by Mr.TinDC; titmouse by Jason Quinn; creeper by joseph higbee; wren by Dan Pancamo; vireo by Kent Mcfarland; blue jay by Randen Pederson; mockingbird by Ryan Hagerty, under Creative Commons licenses.

“Dog vision” photo by Andrew Morffew.

I have noticed that this article has some similar information in some stories, I have heard from different tribes about birds.