Consider the gray catbird: the tropical long-distance migrant that may well be nesting in your backyard this summer.

Gray catbirds are common, so you may not pay them much attention. But look into the research, and you’ll find that this backyard bird is full of surprises. Let’s take a closer look.

As I write this, a gray catbird is singing in my backyard.

It arrived here in New Jersey several weeks ago and may already be building a nest with its mate somewhere in the neighborhood.

I am wondering where my catbird spent its winter – and whether this is the very same catbird that was in my yard last summer. Research on catbirds can help answer these questions.

Every spring, dozens of species of migrant songbirds make their way north from the tropics to settle into nesting habitats across North America. Indeed, half of all North American birds spend their winters south of the U.S. border – from Mexico through South America.

Most of these species are habitat specialists and we might see them in our backyards only briefly during migration as they make their way to more remote places.

The gray catbird, on the other hand, is a migrant from the tropics that is quite happy to claim a breeding territory in a wide variety of shrubby habitats, including suburban backyards.

The catbird singing in your backyard this spring is likely the same one that was there last year. Individual catbirds (and numerous other species) return to the same habitat patch to nest year after year, as long as they are fortunate enough to survive from one season to the next. Studies have shown a roughly 60 percent annual survival rate for catbirds.

If your backyard catbird has a lucky streak, you could see the same bird coming back for many seasons. The longevity record for a catbird is 17 years, 11 months.

This nearly 18-year-old bird was caught and banded as a young of the year in Maryland and miraculously encountered again by banders those many years later in New Jersey.

Banding can confirm the age of birds and also confirm that the bird in your backyard this year is the same one that was there last year.

Participants in programs like Neighborhood Nestwatch can observe their backyard catbirds wearing unique combinations of colored leg bands. These identify each bird as an individual and can be viewed with binoculars. For this project, researchers and participants alike can make observations on the identity and longevity of their catbirds.

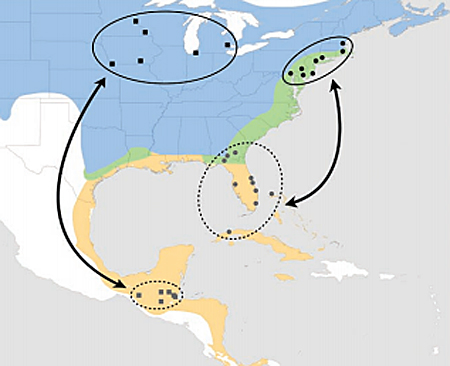

Catbirds nest in 46 of the lower 48 United States and across southern Canada. They spend the winter across an equally broad area. A proportion stay in the U.S., where they primarily occupy the Gulf Coast and Florida. Some hearty individuals hang in there as far north as New Jersey.

Others go further south to the tropics – to the forests of Mexico, the Caribbean and Central America. There, they share the woods with jaguar, tapir, fer-de-lance and toucans.

Catbirds return to the same site on the wintering grounds every year as well. Your backyard catbird might spend the winter in the shadow of Mayan ruins in Guatemala or perhaps in the Florida Everglades.

We can make an educated guess on where your backyard catbirds spend the winter thanks to a recent analysis of banding records along with the use of tracking devices.

What this work tells us is that if a catbird breeds in the upper Midwest, it is more likely to be spending the winter in Central America. If it nests in the mid-Atlantic and New England, your catbird is likely spending the winter in Florida or the Caribbean.

As more studies like this one are carried out, we will have a further refined picture of “migratory connectivity” between nesting and winter sites. And we will be able to make even better guesses about where our backyard catbird might be next winter.

“A Few Raisins Give Him the Greatest Delight”

If you want to kick things up a notch for your backyard catbirds this summer, in addition to providing water, you can also offer them fruit.

As the poet Mary Oliver observes in her poem “Catbird”: “But a few raisins give him the greatest delight.”

One of the pleasures of a birding holiday in the tropics is watching birds at fruit feeders. After hours of seeking difficult-to-see skulking birds of the undergrowth and fast-flitting birds of the high tree tops, birding respite can be found at lodges and cafes that maintain fruit feeders for birds. Dozens of species of brightly colored birds come into easy view to eat banana, papaya and citrus at close range.

Catbirds bring a bit of this culture back with them from the tropics and are among the few birds at our northern latitudes that will readily eat soaked raisins, sliced orange and even grape jelly.

Back to my well-fed catbird. Is he the same bird as last year? Without banding him, I can’t know for sure. But I do know that he will do everything within his power to return here.

And return from where?

Maybe it is time to combine science with imagination. The science tells me that he wintered somewhere in Florida or the Caribbean.

But for better spatial resolution, my imagination is saying the Zapata Swamp of Cuba. Listen to what he sounds like there (in the audio file) … and then listen for the catbird in your yard!

A catbird flew into my slider door and fell to the patio.I went outside sure it had broken its neck and was dead but it moved a bit. I got a box and lined it. The bird was alert but not moving around, not moving its head,just blinking. It let me pick it up with my gloved hand to transfer it to the box. I left it on my patio table, going back every 15 min or so to check on it. It actually let me touch its feathers and check its legs for a break. I’m surprised it actually let me stroke its feathers. After about an hour it hopped out of the box, perched on the end of the table for another 10 minutes, and then took off. I could hear its mate calling it up in the woods.

I noticed a friendly bird while mowing today and was wondering what it was. I live outside of Rochester, NY and only a couple miles from Lake Ontario. Thank for the information as now I know this bird has the pretty songs I have wondered about.

A single Catbird has been hanging around in a residential yard in thick brush in and around a holly tree eating the holly berries since 3rd week December 2024 . Location: North Tacoma near the University of Puget Sound. A rare a sighting this far west that has been confirmed by experienced members of the local Audubon Society. More secretive than a Towhee the Grey Catbird tends to stay lower down in the bushes than a skulking Towhee but does come up higher in protected brushy locations briefly. Beautiful slate grey, black beak, big black eyes and a long tail. Almost impossible to see when in the middle of the holly tree but gives itself away with a variety of unique calls. I’m putting out some soaked raisins to draw catbird in closer so I can get a clear picture.

I’ve lived in my house in SW lower Michingan for about 30 years now. Only a few years ago I heard that WAA WAA sound for the first time but could not spot the bird making it. Posted the audio on youtube and someone told me catbird. Well… last summer I got a glimpse of them a few times and sure enough, catbirds. THIS YEAR! WOW. I poked my head into some bushes and started answering them WAA WAA…. The rest of that day I had cat birds following me all around the back yard. I’d sit, they would make a wide circle around ME, perching every few feet and hollering at me. They are not shy anymore. And abundant. Which I’m delighted since I watched one nab a bug in mid flight. GOOD bug eaters.

We had an unusual friendly catbird this year. He was not afraid of us. He spent everyday in our backyard, and was very verbal. We put out bananas, oranges, bread, and chicken which many of our birds enjoyed.

He had a few babies and they started joining him in the backyard, he would take piece of bread and feed them.

So, I bought the grape jelly for him (we named him Fred) and we noticed he’s not around anymore. We haven’t seen him in days. We really got so use to him being there every day, doing is cat sounding bird calls. He would sit on top of the chair next to my husband’s chair every afternoon and once landed on his knee!

Do catbirds leave the backyard once their children are independent? There is a catbird who looks a little like Fred and we think it’s one of his children. He’s much shier than his dad.

We guessed that Fred must have been living in a very touristy area in Florida or the Caribbean because he was so comfortable being near us and expecting us to provide treats for him.

My yard has had a couple of catbirds every summer since I moved here in 1979. But this is the lst time one of them was so friendly.

I live in the suburbs of Philadelphia and I have many fruit trees and berry bushes. I have a catbird with a nest in a rose bush vine at my front door. In my yard I have red raspberry bushes and every day I go out to pick them this catbird attacks me. Pokes my back. Tangles my hair. I yell at her and she yells at me. It’s a little crazy here at berry season. My question is can anyone think of a way to get her behavior to stop. This is the 3rd year for this

Just redid our yard with many bushes and plants and we have this crazy catbird (and finally saw his wife today) claiming the whole shebang!!

I hope the birds claim our yard, eat the mosquitoes and stop mocking my indoor kitty🤣

Love from North Jersey USA

Thanks so much for writing–we have a family of catbirds in our yard that seems to do the same thing to our indoor cat. Poor Hobbes just sits in the window and watches them and it really seems like they’re taunting him.

I have had catbirds for years, and each year they would follow me around the yard, just singing away or making noises at me. Sadly, one of them 5/25/23 flew into an open door and didn’t make it. It has bummed all of us and now it is super quiet to us. Yes, we have many other types of birds, but these were the ones that seemed to know us. But, where did the mate go? And how do I get it to come back or attract other Catbirds?

I’m in Virginia and suddenly we have catbirds this spring. I have never seen them and have lived here for decades and never seen one. My roommate suddenly began hearing birds that she said sounds like a kitten. There are allot of them. They’re very friendly and like to peek in windows and doors.

QUESTION: I’m in the Poconos of Pennsylvania. Every year I have several pairs of orioles and even more pairs of catbirds that return annually. Normally they all leave around the same time to migrate south. I feed them grape jelly all summer until that happens. This year the resident orioles left around the end of July. The catbirds were still here. In the meantime, another group of migrating? orioles arrived in mid August and stayed here for several weeks before taking flight. It is now almost the end of September and the catbirds are still here. Should I stop feeding them to encourage them to move on?

Gray catbirds may not be found year-round in Cape May, but they’re certainly here in abundance in Southeast Pennsylvania all year. In summer, I sometimes see them eating spotted lanternflies as well as other insects. They also occasionally peck my ripening tomatoes. In the frost and snow season, they eat out of my bird feeder. Cornell’s map shows them as non-migratory on the Eastern Seaboard.

https://www.allaboutbirds.org/guide/Gray_Catbird/maps-range

Grey catbird’s singing ability outstanding. Many reviews of his song use words like”discordant “ or “ not melodic” My humble opinion is that he has a ton of talent and nobody in New England works harder,singing right through hot early July mornings long after most other songsters break off until late afternoon. It’s mostly over by the second half of July, but a few birds keep it up till August 1st.

We live in Ocean County, NJ and have made our fairly large backyard welcoming to both resident and migratory birds. Several catbirds arrive in early spring and each year there is a nest in a forsythia

“thicket” . We didn’t realize that they lived as long as they do and that it may be the same birds year after year. Is it possible that they get to know us and therefor seem to be more and more comfortable being

very close to us when we are outdoors?

Great article now we know what type of bird this is in our neighborhood we so enjoyed this article very informative ??