If you want to research migratory songbirds, you have to catch them first.

Each spring, licensed bird banders across the country set up shop to capture and collect data from the millions of migratory birds returning from their wintering grounds in Central and South America.

I recently spent a day with a bird-banding team from the Smithsonian Migratory Bird Center (SMBC) at the Conservancy’s Clive Runnells Family Mad Island Marsh Preserve in Matagorda, Texas — the epicenter for studying neotropical migrants that cross the Gulf of Mexico on their journey north.

Here’s what it’s like to be a bird bander for a day at one of the most productive avian research spots in the country.

Open For Business

It’s 7:00 am and we’re bouncing along a well-grooved dirt road through the marsh. The sky is a warm grey, and the humming of mosquitoes is already audible over the rustling grass.

After winding through a tangle of scrub, the road hits the shoreline and peters out amid prickly pear cactus and flowering Texas mountain laurel, which smells uncannily like grape soda. Tim Guida, a research technician at the SMBC and lead bander, pops the trunk and we set to work unloading the gear — we’re on the clock, and the birds are arriving.

Banding assistants Danielle Aube and Lauren diBiccari grab a massive blue rubber tub packed with banding equipment, data sheets, binoculars, and bug spray, and Guida follows with an insulated cooler. While diBiccari raises the tent, Guida and Aube don headnets and plunge into the mosquito-laden scrub.

About 20 mist nets are already staked through a maze of narrow trails shaded by netleaf hackberry and yaupon holly, but they need to be unfurled every morning. After removing the neon ties, Guida and Aube deftly unwind and raise the nets, which are made of delicate, black nylon mesh specially designed to help scientists capture birds or bats.

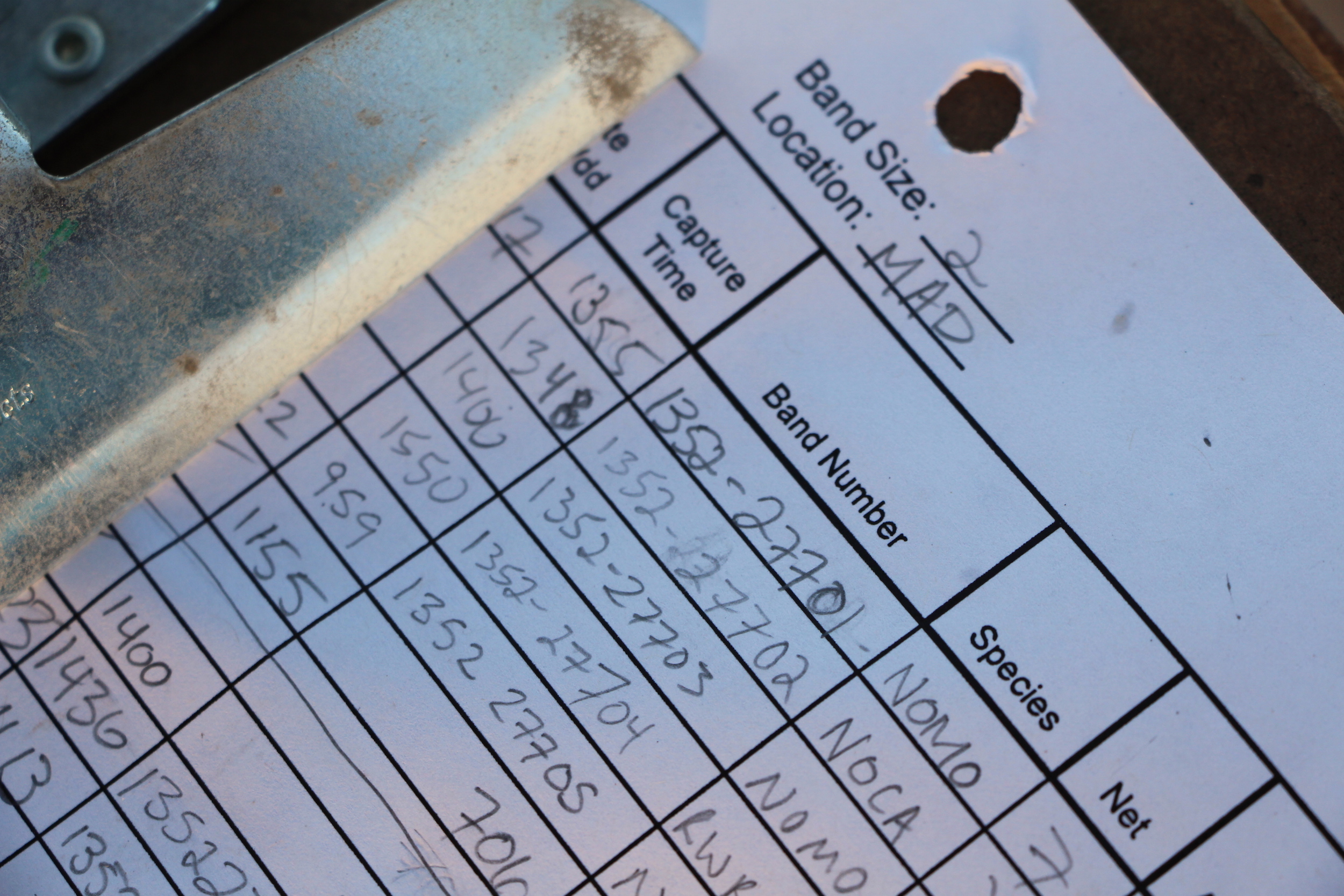

Meanwhile, diBiccari is setting up the banding station: data clipboards, pencils, various sizes of bird bands, tools and toolbox, blood-sample station, cloth bags and wooden boxes for birds, and the requisite stack of field guides (birds, wildflowers, butterflies, etc). Everything in order, she takes weather readings, noting the temperature, wind speed, humidity, and cloud cover.

Setup complete, we all douse ourselves in bug spray and gulp down a bit of black coffee. Then the waiting begins.

Interval Game

“White-eyed in net 3A, 8:35am.”

Back at the tent, Guida’s voice crackles over the yellow walkie-talkie. He is out on one of the first net runs of the day — the team alternates checking the nets every 20 minutes for captured birds. On a good day they’ll keep this up for a good 7 or 8 hours into the late afternoon.

About five minutes later he returns, carefully carrying a cream-colored cloth bag. Inside is a white-eyed vireo, a common catch for the area. Loosening the drawstring, Guida pulls out the bird and sets to work collecting data.

White-eyed in net 3A, 8:35am.

Tim Guida

Band, Blow, Measure, and Weigh

After selecting a size 0 band, Guida records the band number — 2750.43984 — and tightens it around the bird’s right leg. Next, he snips off a toenail sample into a small manila envelope and plucks the fourth feather on the right side of the vireo’s tail. Future SMBC researchers can use these samples to study the timing of migrating birds.

Envelope labeled, it’s on to the fat check. Guida blows gently on the bird’s chest to reveal the tightly stretched, pink skin and muscle hidden underneath the feathers.

“When birds fly across the Gulf, they burn off all of their fat and then their body starts to burn their own muscle for fuel,” explains Aube. “Some birds we catch look like skeleton birds.”

Chest fat and muscle are measured on a 1-to-5 scale. This vireo had a fat score of 1 and a muscle score of 2, meaning that he is fairly lean, possibly from an evening spent crossing the Gulf. (White-eyed vireos both migrate through Texas and reside there year-round, so it’s hard to tell exactly where this bird came from.)

That’s why places like Mad Island are so important to migratory songbirds that need good habitat to rest and refuel after the Gulf crossing, which can take a songbird about 18 to 24 hours to complete.

“Because of its location and unique plant community, this place ends up being a vital stopover for birds,” says Steven Goertz, the Conservancy’s preserve manager.

After jotting the fat and muscle scores on the data sheet, Guida continues blowing on the vireo to check for ticks. SMBC researchers are also studying the ticks and tick-borne pathogens that migratory songbirds are bringing to the United States. But lucky for the vireo, it’s tick-free.

Nest step: measurements. Measuring the body length of a squirming, feather-covered bird intent on escape isn’t easy, so banders measures the bird’s tarsus, or leg bone, as a proxy for overall size. They also measure the wing chord, the distance between the bend in a bird’s wing, or wrist, and the tip of the longest feather. While measuring, Tim also examines the bird’s feathers to try and determine its age and sex.

The last measurement is undoubtedly the least dignified — Guida tips the vireo head-first into a toilet-paper tube and places it gently on the scale. As strange as it sounds, it works. Feet dangling, the bird can’t stretch it’s wings to escape, and the weight of the tube is subtracted from the bird’s weight — a mere .38 ounces.

Release and Repeat

Weight recorded, Guida pops the bird out of the toilet-paper tube and back into his hand. The vireo has held its composure during the entire process, despite delivering us a steady, indignant stare and attempting to bite Guida’s thumb a few times.

Banding complete, Guida carries the vireo out of the tent and releases his grip — the bird promptly high-tails it back into tamaulipas thorn scrub. A few minutes later, we hear its distinctive, explosive tick-a-purrrr-cheet call ring out from a nearby hackberry.

The birds trickle in throughout the day — the first days of April are still early into the migration season — and the banding team works through them efficiently. Lincoln’s sparrow, northern cardinal, brown thrasher, ruby-crowned kinglet, ruby-throated hummingbird, and more white-eyed vireos.

Now in its fourth year, the Mad Island banding station typically processes between 2,000 and 3,000 birds each spring.

By their count, today’s banding is leisurely — with ample time in between birds to scan the bay with a scope and identify the newly bloomed wildflowers spilled along the paths. But everything can change when the weather is just right.

“Mad Island really shines when you have north winds and the birds need somewhere to land,” says Guida. “This habitat is pretty welcome after a Gulf crossing in bad weather.”

Guida recalls a major fallout event during late April of 2013, when the team filled eight boxes (of eight birds each) and 40 bags on the first net run and still had to let 30 birds go because they just couldn’t process them fast enough.

“It was like a hailstorm of birds,” he says. “You’d look up and there would be a flock bombing in from a cloud, whizzing by our heads as they landed.”

It was like a hailstorm of birds, you’d look up and there would be a flock bombing in from a cloud, whizzing by our heads as they landed.

Tim Guida

Closing Up Shop

After the wind picks up and three net runs turn up empty, it’s time to pack up for the day. We reverse the morning’s work: lowering, winding, and closing the nets, carefully packing up the samples and equipment, and loading up the car.

One day down, another seven or so weeks to go. It’s been hard, hot, buggy, and rewarding work — the data we collected will help fuel research on the where, when and how of bird migration along the entire Gulf coast.

But our day isn’t quite over: on the drive back to the lodge we take a detour and do what birders do best — go birding.

I had the opportunity to assist a researcher with capturing and banding Nelson’s and Saltmarsh sparrows on the eastern shore of Virginia this past winter. It’s not quite as leisurely when you have to walk through the sucking mud to scare up birds, that’s for sure! The tube weighing and blowing air on the birds’ chests were the most vivid parts for me as someone who had never seen banding before. As were the little white baggies we placed the birds in while they were waiting to be processed, bags which jumped and peeped while they were hanging from a bush.