Consider the octopus: media darling of the invertebrate world. Lately, it’s hard to escape popular reports of the clever octopus, often featuring video of the eight-legged critter opening a jar.

Some even suggest octopus intelligence rivals our own. And indeed, many captive octopuses find ingenious ways to escape their enclosures. One was recorded throwing rocks at aquarium glass.

And then there are the individuals who pick Super Bowl winners better than any ESPN commentator.

All this adds up to a lot of octopus love.

Despite all that, we know very little about their basic life history in the wild.

“There is so much passion for octopus right now,” says octopus researcher Ily Iglesias. “But that is contrasted with how little knowledge about them is actually out there.”

Iglesias, a former Nature Conservancy Marine Fellow now working for NOAA, knows well the allure of octopus. She came across her first one as a young child exploring tidal pools in the Pacific, and has been smitten ever since.

But now she explores the world of the octopus not just out of intellectual curiosity. Gathering accurate life history information for one species found in Hawaii, Octopus cyanea, matters for conservation, too.

The octopus may have celebrity status among internet critter fans, but it’s also popular as a food source. Many people in Hawaii — where Iglesias conducted her field work — hunt, eat and sell octopus.

As if underscoring this fact, as I worked on the first draft of this story in an Oahu hotel, a man looked over my shoulder to see what I was writing, and then whipped out a photo of an octopus he had speared. That afternoon.

“Everyone here hunts octopus,” he said with a grin. “My grandfather did. My dad did. It’s in the blood.”

But without basic information about the species, it’s difficult for fisheries managers to create sustainable regulations.

It’s the very definition of what conservationists call a data-poor fishery.

“The octopus has always represented the mystery of the ocean,” says Iglesias. “My job was to uncover some of that mystery.”

Easier said than done for an elusive, intelligent creature that is extremely well camouflaged amongst the coral and rocks of the ocean floor (the octopus’ garden, if you will).

But fishers know the octopus. They have a passion for the animal and want to see it thrive. And they can supply a ready supply of samples.

Using the fisher’s samples, researchers like Iglesias are seeking to gain a population-level picture of the octopus, including age structure and rate of growth.

And how is that determined?

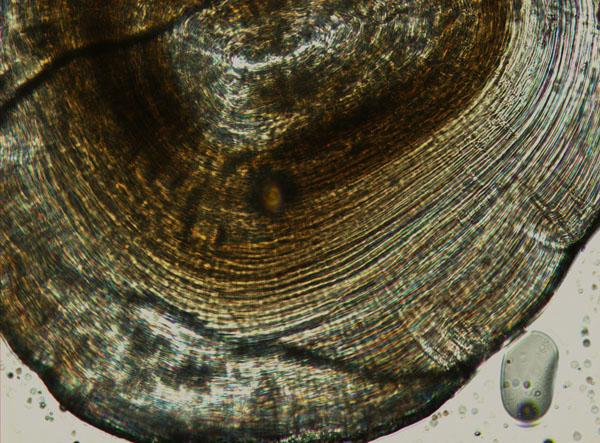

By dissecting a thin sliver of an internal structure of an octopus called a stylet. These are rudimentary shells, pictured here on either side of an octopus lung.

The octopus stylet has growth rings similar to a tree’s rings (or a fish’s otolith). But an octopus’ growth rings don’t represent years, they represent days.

Researchers can actually determine the octopus’ birthdate by counting rings.

It’s a delicate operation, requiring a steady hand and a powerful microscope. The stylet samples are immersed in an oil that smooths out rough spots on the samples, making it easier for researchers to count rings.

The rings are counted on a computer screen attached to the microscope. They’re counted from the center, just like tree rings.

By aging the octopus and comparing this to its weight, researchers can determine its rate of growth. They are also looking at when octopuses mate.

Researchers also determined octopus gender. (In case you were wondering, males often have enlarged suckers, and their third arm is longer than the other seven).

An important factor in determining the sustainability of a population is the amount of time it takes for individuals in the population to attain sexual maturity as well as the timing of reproductive events.

Beyond this, researchers wanted to know how many octopuses are out there. Right now.

Looking at one area of Hawaii’s Big Island, Iglesias wanted a scientifically defensible way to determine octopus abundance.

So she looked to fishers, the people who know octopus best and for whom the species has long-standing cultural importance.

Community members went out and searched reefs in circles, counting octopuses they saw.

This world of octopus research – counting growth rings, looking for enlarged suckers, counting octopuses on the reef – may not capture the headlines like the octopus that picked the Patriots to win it all this year.

Still, the future of the octopus rests in gathering and utilizing such information.

“The octopus has really attracted a lot of attention in popular culture today,” says Iglesias. “But it has been important in Hawaii for millennia, a part of the diet and culture. This research will hopefully benefit the people who revere octopus most, by combining traditional knowledge with modern science.”

“But gaining better information about octopus life history benefits everyone who loves these animals,” she adds. “The more we know, the better we can manage them in the future. For all the attention octopuses receive, it can be jarring to see just how little we know about them.”

Join the Discussion

2 comments