Mollusks and ocean acidification don’t get along — but how will that impact fisheries and fishing communities?

New research from The Nature Conservancy and partners reveals which regions in the United States will feel the impacts of acidification first, and which communities are most vulnerable to acidification’s effect on shellfisheries — including oysters, clams and mussels.

“Risk is a combination of acidification exposure and social vulnerability, but these considerations are rarely, if ever, put together,” says Mike Beck, lead marine scientist at the Conservancy and author on the paper, which was recently published in Nature Climate Change.

Changing Ocean Chemistry

The ocean has already absorbed an estimated 25 percent of human-generated carbon dioxide in the atmosphere. While this slows the effect of climate change, it’s not without consequences — dissolved carbon dioxide lowers the pH of seawater, making the ocean more acidic.

“Shellfish and corals are particularly susceptible because they need to secrete calcium carbonate to grow,” says Beck, “and this becomes more difficult with greater acidification.”

An increasingly acidic ocean is already harming some shellfish fisheries in the Unites States, like the Pacific Northwest oyster fishery.

Although science is beginning to pinpoint which areas will be the most exposed to ocean acidification, there has been little consideration of how this will affect people and vulnerable fishing communities in those places.

To answer these questions, scientists from the Conservancy and partner organizations completed one of the very first risk and vulnerability assessment for shellfisheries and fishing communities in the U.S.

The Where and When of Acidification

As part of a team led by Julia Ekstrom, from the Natural Resources Defense Council, Beck analyzed which regional U.S. mollusk populations will be exposed to ocean acidification, how sensitive those species are to increasing acidity, and how vulnerable fishing communities are to acidification.

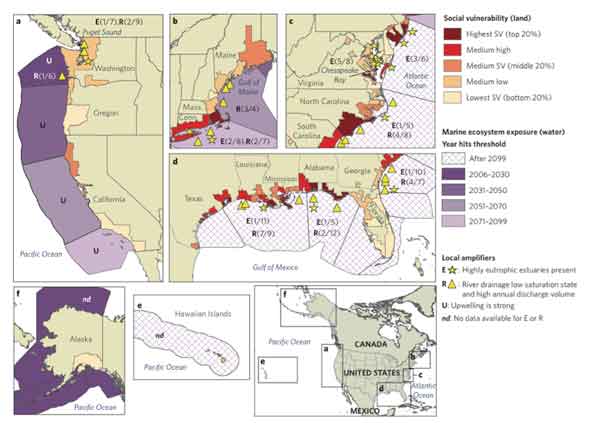

They found that 16 out of 23 regions in the U.S. are already exposed to rapid ocean acidification, or at least one amplifier. Amplifiers — like coastal eutrophication, upwelling, and river drainages — increase local risk of ocean acidification.

Both the marine ecosystems and mollusks in the Pacific Northwest and Southern Alaska will be exposed soonest to rising acidification, according to their results, followed by the north-central West Coast and the Gulf of Maine.

Additionally, pockets of marine ecosystems along the East and Gulf Coasts will experience acidification earlier than global-scale projections suggest. This prediction is especially worrying, as the Southeast and Gulf of Mexico are home to the communities that the researchers identified as most vulnerable to acidification.

When exposure to acidification and social vulnerability are combined, acidification risk is somewhat evenly spread across the country. But each region will require different solutions, depending upon their combination of exposure and social vulnerability.

Local Solutions to Acidification Vulnerability

Beck and his colleagues recommend solutions for at-risk regions to reduce some amplifiers of acidification. “Fishing communities should diversify their fisheries,” he says “and consider local measures that can reduce acidification risk, like reducing nutrification.”

Shellfish are some of the most lucrative and sustainable fisheries in the country, and declines could negatively impact not only ocean ecosystems, but fishermen, local economies, and our food supply.

“We are rapidly acidifying estuaries from excess nutrients,” says Beck, “and addressing this local problem right now, while we work to mitigate global climate change, will reduce risks to fish, fisheries, and fishing communities.”

Join the Discussion