So many of the amazing things we learn about birds require getting those birds into a researcher’s hand.

With a bird in hand, a researcher can take measurements and samples, attach identifying markers, or mount migration tracking devices.

But to get the bird in hand, you have to catch it first.

And catching a bird requires some magic tricks. One such bird-catching trick involves using a decoy – a fake bird.

Enter the decoy.

In using a decoy, researchers capitalize on a bird’s territorial nature in order to lure them into catching range.

Mirror, Mirror: Why Fake Birds Work

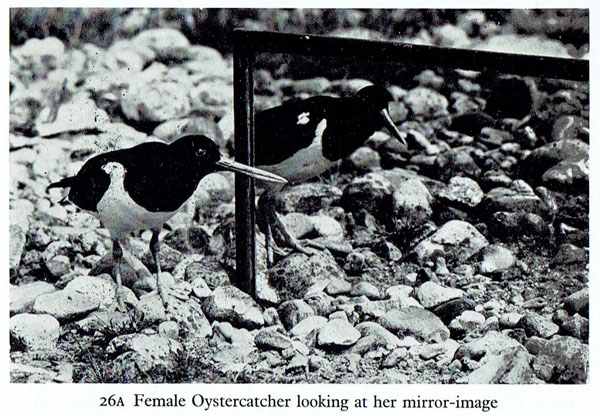

To understand why decoys often work, let’s consider birds and mirrors.

Have you ever seen a bird attacking its own reflection in a window or a car’s rearview mirror? This is an expression of territoriality.

For many avian species, the world is carved up into bird neighborhoods composed of exclusively-occupied territories of individual birds or male-female pairs.

You might be asking the question, “Why doesn’t the bird recognize itself in the reflection?”

Using behavioral psychology terms, we would say that reflection-fighting birds have failed the “mirror test.”

Only a few animal species have been shown to be able to recognize themselves in mirrors. These include humans, great apes, dolphins, killer whales and at least one bird, the European magpie .

Most birds, though, interpret their reflection as another bird.

The fact that our backyards are “owned” by individual birds or bird pairs usually escapes our notice. But when we see birds fight with each other or with their own reflections, we are reminded that the birds around us are in a constant struggle to maintain their place in the world.

Food and other resources are limited and winning a high quality territory is one way for an individual bird to ensure that it will have the resources it needs for a successful nesting season and other priorities.

Both a car’s rearview mirror and a decoy represent, in research parlance, a simulated territorial intrusion.

Of course, not all birds are territorial and some are territorial only for part of the year.

For example, the duck decoys used to hunt ducks attract ducks not because these birds are itching for a fight, but because ducks like to flock up in the winter. In the case of ducks, birds of a feather flock together.

Souped-Up Decoys: The More Realistic, the Better

While hunters can buy all the duck decoys they want, most bird researchers can’t buy a ready-made decoy version of a warbler or sparrow at the nearest Cabelas.

They need to be more resourceful to come up with lifelike renditions of their study species.

I have seen decoys that researchers crafted from wood, paper mache, craft store feathered bird figurines, taxidermy and lately, 3-D printers.

A researcher can even commission a traditional decoy carver to make wooden decoys for research. Many carvers are glad to have the chance to carve a “working” decoy, because in this generation, hand carved decoys are typically collected as objects of art rather than as hunting tools.

When it comes to decoys, the more realistic, the better. Adding motion and sound to a decoy contributes to its effectiveness.

For example, when studying one fiercely territorial shorebird, the American oystercatcher, researchers added remote control car motors to their decoy so they could make their fake oystercatcher rotate at will.

They also added a remote control speaker to make territorial calls.

Their souped-up oystercatcher decoy resulted in maximum provocation of the territories’ rightful owner.

The decoy, the sound and the motion all do the job of getting the bird we want to capture to a particular spot – but the bird still needs to be caught.

Building a Better Bird Trap

Although birds get pretty distracted when they think they need to vanquish an intruder, they are not so distracted that you can walk over and pick them up. You need a trap.

There are various nets and traps tailored to the nature of the quarry.

In the case of the oystercatcher, one of the traps used is called the “whoosh net.” It’s a bungee cord-powered net that “whooshes” over the bird and decoy when a remote trigger is pulled.

Here’s the decoy and whoosh net in action, catching a pair of American oystercatchers.

It may seem remarkable that wild birds are fooled by — let’s face it — roughly-rendered decoy versions of themselves.

I am certain that you can pass the mirror test, but I wonder what you would do if there was a mannequin in your backyard with a recording that said, over and over again, “This is my backyard!”

You might just wander over to investigate too. And let me warn you: it may be a trap!

The strategy is very interesting, but is it really necessary? In my opinion, if there is already birds from this species being studied, we don’t need to make these traps to capture others. But if it’s a new species, it could be taken just for researches.

Hi Linda,

Thanks for your question. Blog author Joe Smith has this response:

Catching and handling birds is done with great care by trained folks who do everything they can to minimize stress to the birds. Many research studies follow banded populations of birds over seasons and sometimes across many years. Through the course of these studies researchers get know previously captured birds as individuals, monitoring them for several months to document, for example, nesting success. Captured birds typically get right back to business after being released , maintaining territories and raising young.

Does trapping & netting harm these birds health? They have to be scared, & under “high Anxiety”, until released.

If they are tagged, perhaps they can be followed, for their long-term “health effects”??