Small island developing states, SIDS as they are known in development circles, face grave risks from hurricanes, tsunamis and sea level rise. But they also depend heavily on fisheries for both food and income. When their fisheries are in poor shape – whether from natural hazards or ineffective management — it becomes that much harder for them to bounce back from disaster.

On the upside — many actions that help enhance fisheries and fisheries habitat would also help buffer shorelines from storms and erosion. That’s one of the conclusions of the Coasts at Risk report released July 30 at The Nature Conservancy.

The report finds, for one of the first times at a global scale, a significant link between environmental degradation and disaster vulnerability — meaning not just a community’s risk of being hit, but the ability to resist and recover from natural disasters.

“It’s a significant correlation,” says Michael Beck, the Conservancy’s lead marine scientist and the report’s editor. “When you think of all the other factors that contribute to risk — such as impoverishment, lack of care facilities, poor governance, low GDP — even with all of those other things considered, to still have a clear and important link between environmental degradation and social vulnerability, that’s really important.”

The report is based on the Coasts at Risk Index (C@R), which starts with WorldRiskIndex, updated each year by the Alliance Development Works, and adds several key environment-related indicators, such as the status of fish stocks, the role of fish in the country’s diet, income from marine activities, and (for tropical countries) the storm defense that is offered by mangroves and coral reefs.

In temperate regions, salt marshes and oyster reefs offer similar benefits, but could not be included in the report because — surprisingly — there just wasn’t enough data on their status.

New Potential for Risk Reduction

Globally, 23% of the population lives within 100 km of a coast. That’s predicted to increase to 50% by 2030. Governments and aid agencies can’t change storm paths or block tsunamis. It’s difficult to convince people to move away from the coasts. But there are many ways to reduce the social and financial impacts of those hazards.

Typically, the focus in that effort has been on built capital — improving building codes, availability of hospitals, evacuation plans, distribution of aid, etc. But this report makes clear that attention to natural capital — improving coral reefs and mangroves that buffer shores and improving fisheries to enhance food security — could also go a long way toward reducing the human cost of coastal hazards.

The report also recommends some changes for environment and disaster aid groups. Many marine conservation efforts now focus on the most remote areas – where biodiversity is high and reefs and mangroves have not yet been badly damaged. Doing more to improve the coastal environment near densely populated areas would have a much larger effect on vulnerability to storms and flooding.

Conversely, disaster aid groups like the Red Cross and CARE have not often paid much attention to the health of fisheries or coral reefs. The strong correlation between environmental degradation and vulnerability to coastal hazards points toward the potential for incorporating those approaches in a broader plan.

Data for Decisions

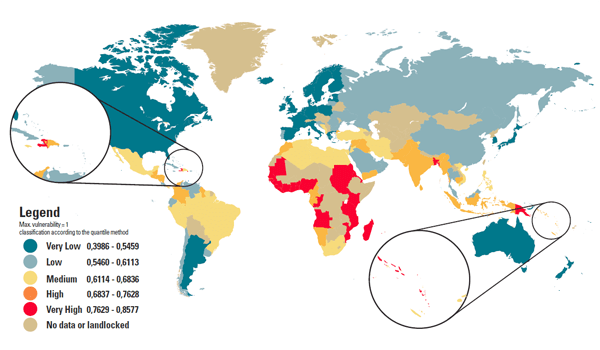

The most obvious output of the C@R index is a ranking of countries at greatest risk from coastal hazards. Adding environmental indicators shifted those rankings in some surprising ways, says Beck. Oceanic islands in the Australian and Indian Oceans remained highly vulnerable, but Caribbean islands — where fisheries and coral reefs have experienced significant losses— rose in their risk and vulnerability ranking. Overall, the most vulnerable nation in the expanded ranking is Haiti, the nation most exposed to coastal hazards was St. Kitts and Nevis and the nation at the greatest overall risk when exposure and vulnerability are combined was Antigua and Barbuda.

The idea that nature helps protect people from storms and floods is hardly new. Readers of Jared Diamond will certainly recognize the report’s findings as familiar. What’s different here is that the evidence isn’t limited to a few case studies or examples, however compelling they may be.

The new index allows comparison across 139 countries and examines both built and natural capital. When policy makers are seeking solutions to the new and expanded risks that many nations will face in a changing climate, the data presented here will help them to consider improvements to reefs, forests and fisheries alongside breakwaters, dikes, reservoirs, and emergency food aid.

“It’s all just stories until you put some data to it, says Beck. “When you put data to it – across all these nations – you really do see a link.”

Join the Discussion