Call up in your mind the classic travel ad picture of a tropical island: turquoise waves lapping gently at a white sand beach, palm fronds waving in a mild breeze.

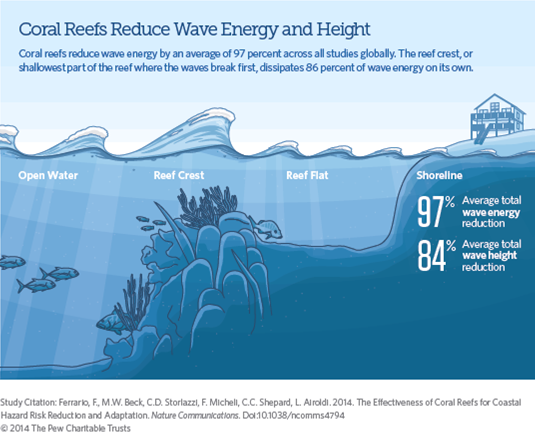

Now direct your view off shore. See that line of white foam, just shy of the horizon? That’s the crest of a coral reef that extracts over 95% of the energy from incoming waves. Without it, the waves wouldn’t lap so gently.

Coral reefs get lots of attention for the biodiversity they harbor — and for the threats posed by warming and acidifying oceans — but there’s been very little work done on the value they offer to coastal communities worldwide.

Reefs v. Breakwaters: Just as Good at a Fraction of the Cost

A group of researchers, including the Conservancy’s Michael Beck and Christine Shepard, combed the literature on corals and wave breaking. They extracted quantitative data from 27 studies of wave breaking in the Atlantic, Pacific and Indian Oceans — and they found that intact coral reefs reduce wave energy by 97% and wave height by 84%. The study is published this week in the journal Nature Communications.

Of course, it’s possible to construct breakwaters to do a similar job, but they are far more expensive. For 29 projects the authors surveyed, the median cost of breakwater construction was 15 times that of reef restoration. And when a concrete breakwater starts to crumble, someone has to go fix it. A living coral reef has the potential to repair and maintain itself.

These figures put the ongoing degradation of coral reefs in a new light. The authors calculate that about 100 million people live within less than 10 m above sea level and less than 10 km from a coral reef. They receive substantial benefits from the reefs — even if they never grab a fishing pole or pull on a mask and fins to enjoy the beauty of that watery world.

Restoring for Protection Means Location Matters

The study suggests a somewhat different way of approaching coral conservation and restoration. Right now, remote biologically-diverse reefs are the most common targets of conservation organizations. But focusing more on reefs closer to population centers would offer much greater coastal protection benefits and might also generate increased support for restoration.

“Adaptation funds are about helping people,” says Beck. “That could mean much more support for reefs near people; these reefs won’t be nearly as beautiful — they’ll often be a bit run down. But it is exactly these reefs that — if restored and conserved — could do the most good for the most people.”

Restoration methods include both structural support in which in which rocks or concrete balls offer corals a better foothold — and coral transplantation in which naturally broken bits of coral are harvested, cultivated and transplanted back to a living reef.

What about Bleaching & Acidification?

And what of all those pessimistic predictions about coral bleaching and ocean acidification? Though the threats are real, Beck sees cause for optimism. Of the major types of habitat that serve to protect coasts, there are more coral reefs remaining (70%) than mangroves (50%), marshes (50%) or oyster reefs (15%).

Scientists are also finding that corals can recover after bleaching events. When water temperatures rise, corals eject the single-celled algae called zooanthellae that give them color and help feed them. If conditions improve, the corals can recover. There is also some evidence emerging, that the zoothanthelae, with their short life cycles, may be capable of rapid evolution in response to climate change.

“Even when we’ve seen severe bleaching — as in 1998,” says Beck, “we’ve seen that coral reefs can recover. What we know is that we can reduce other impacts, and when we do, bleaching will have less of an impact.”

Oceans have a future to ensure the communities Sustainable Happy Sustainability 2015

Without the reefs we have no oceans… You idiots…