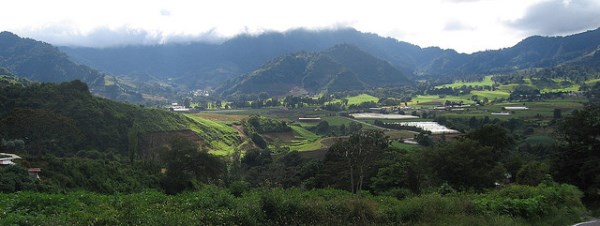

Islands of forest in a sea of crops…that’s how people often think of tropical forest remnants (and the species that live in them) in places like Costa Rica or Indonesia.

And that image is why ecologists have used island biogeography theory (IBT) — first laid out in a 1967 by Robert MacArthur and E.O Wilson to describe species distribution on islands — to explain and predict biological diversity and species loss rates in these patchwork landscapes as well, and to design and site biological reserves for tropical forest remnants.

But an article published this week in the journal Nature casts doubt on the utility of IBT for non-island landscapes — particularly for the croplands in between forest remnants that this use of IBT treats as “water” between the forest “islands.”

And those croplands, the authors argue, present substantial opportunities for biodiversity conservation.

“In the island system, island biogeography works really well,” says co-author and Stanford University-Nature Conservancy NatureNet Fellow Daniel Karp. “But when you apply it to the countryside system, it kind of falls apart.”

Agriculture Is Not Ocean

The authors compared the distribution of bat species in a true island environment with the distribution in a landscape of forest fragments embedded in coffee plantations and pastures to see whether the theory worked equally well in both places.

The results of this study demonstrate that there is a lot more going on between forest remnants than there is between islands. Open water (where no bats live) is not the same as coffee farms and pastures (where this study shows many bats live, though not in the same density or groupings as forests).

The importance of this finding goes well beyond ecological theory. Over half of the world’s land surface area is now used for rangeland or crops. To a large degree, the field of conservation has been treating those areas as if they have zero value to biodiversity.

“There is a big gradient between preserves and nothing,” said the paper’s lead author, Chase Mendenhall, a Stanford University PhD student, working with Dr. Gretchen Daily. “As biogeographers, we have been using these models that treat everything as water. When we do that, we are essentially forfeiting the opportunities that we could have if we were being more careful.”

Dinner Chat at Las Cruces Sparks Comparative Study

The study came about almost by accident. A group of Stanford University ecologists, including Karp and Mendenhall, were netting bats in a set of mixed forest and agricultural sites in Costa Rica, in and near La Amistad International Park and Las Cruces Biological Reserve, where the Organization for Tropical Studies has a field station.

Trading big-catch stories at the communal dinner one night, they heard that Cristoph Meyer, a German ecologist, had caught a Vampyrum spectrum, or false vampire bat, the largest bat in the neotropics (and Mendenhall’s white whale). When Mendenhall learned that Meyer was using identical trapping methods to study bat populations on human-made islands in Gatún Lake on the Panama Canal, it spawned the idea for a site comparison.

The study locations were a mere 350 km apart, harbored similar forests and experienced similar climates. The number of sites and intensity of sampling effort was comparable. The scientists soon realized that they could hardly have designed a better experiment for testing the application of island biogeography to forest fragments.

Coffee Plantations Support a Diversity of Bats

Meyer’s results fit the island biogeography theory well — with larger islands and those closer to the mainland supporting more species than smaller and more distant islands.

Mendenhall and Karp found something quite different. In their sites, it made very little difference how far a forest fragment was from the large forest reserves or how large the fragment was.

The agricultural landscape did not serve to isolate forest fragments in the same way that open water isolated islands. In fact, almost one-half of the common bat species were more prevalent in coffee plantations than in forests and only 5 of the 30 species sampled avoided plantations altogether.

As clear as these results were, one study is just one study. So the researchers reviewed 52 other comparisons of bat diversity in island and countryside ecosystems

True islands almost always had lower diversity than mainland habitats, while forest fragments supported as many – sometimes more — species than minimally disturbed forest.

“They’ve shown something that people have appreciated, but that hasn’t been shown so explicitly or so elegantly,” said William Laurance, a professor of conservation biology at James Cook University and an editor of Tropical Forest Remnants: Ecology, Management and Conservation of Fragmented Communities.

Conclusions: Why Nature Reserves Can’t Be Conservation’s Only Approach

If the landscape surrounding forest fragments supports more species than biologists supposed, then conservation scientists may be undervaluing the importance of the matrix in which forest fragments are embedded.

One alternative approach is called “countryside biogeography” — described in a 2006 paper by Henrique Pereira and Gretchen Daily — in which matrix habitats that surround forest fragments are assigned a habitat value from 0 (no value – think parking lot) to 1 (most similar to undisturbed habitat). When there is sufficient data available, this approach allows planners and policymakers to better evaluate the tradeoffs and interactions among types of agricultural development.

For instance, says Karp, the Conservancy is involved in a process to connect the two parks (La Amistad and Corcovado on the Osa Peninsula) that flank the study area. A clearer picture of how to incorporate biodiversity values alongside the values of agricultural production and sustainable livelihoods could result in much better outcomes for this district, which is one of the poorest in Costa Rica.

“The current model of nature reserves works toward separating humans and nature,” says Mendenhall. “That’s good to a point, but it can’t be the only approach. Today, the world’s biodiversity is living with humans, not apart from them. Increased integration looks like the way forward.”

Daniel Karp is a NatureNet Science Fellow. NatureNet Science Fellows Program is a partnership between the Conservancy and six of the world’s leading universities — Columbia, Cornell, Princeton, Stanford, the University of Pennsylvania, and Yale — to create a reservoir of new interdisciplinary science talent that will carry out the new work of conservation.

Meeting the world’s demand for food, water and energy without exacerbating climate change and degrading natural systems is the human challenge of our generation. NatureNet Fellows are just one way that The Nature Conservancy is bringing together the scientific expertise to confront these challenges and find solutions to sustainable well-being for billions of people.

Nice article thank for sharing

Thanks for the great article! Can you correct the spelling of my name? Thanks much!