Counting Sandhill Cranes can be a real challenge. How do you estimate the number of birds that gather by the thousands each evening? A new technology has great potential to help.

Enter the Unmanned Aerial Vehicle (UAV) – a technology you might better know as a drone.

First, a bit of background. The Nature Conservancy has been demonstrating how a working farm can be managed to support migratory birds for more than a decade at Staten Island in California’s Bay Delta.

Millions of migratory birds on the Pacific Flyway depend on the Central Valley and Delta as an important stopover during spring and fall migration, as well as vital overwintering habitat.

We conduct bird counts to determine how the birds are responding to our management of the island’s resources.

The Sandhill Crane is a special focus of our work but it can be challenging to get good estimates of how many cranes are sleeping and foraging on Staten Island.

At the end of a day foraging in the surrounding landscape, the cranes congregate in large numbers each evening and settle down for the night, all packed together in fields that the Conservancy intentionally floods — providing their preferred roosting habitat of 6-12 inches of water.

The scenery and sounds are primal at sundown in the Delta, with thousands of birds flying in to these fields.

Estimating how many birds are roosting at these sites a real challenge. The only option so far has been to count them as they fly in before dark, jotting down their numbers as quickly as possible. But they are not done arriving and moving around until after dark, and counting multiple flocks as they come from all directions is not easy!

To get accurate counts, what you’d ideally want to do is wait until after dark, when they’ve all arrived and settled down, then count them from overhead. A serious challenge.

This spring we tested a new technology that we think has the potential to provide much better bird counts on a regular basis and will help us track populations in ways we haven’t been able to before: Unmanned Aerial Vehicles (UAVs or drones).

UAVs are the new black in tech, kind of like Web 2.0. We’re fielding at least a call or email each week about a start-up or university lab that is looking at novel ways to use drones.

And there’s been some great conservation applications by WWF and conservationdrones.org. At its core a UAV is any type of aircraft (fixed wing or multi-rotor) that can be flown autonomously by providing way points with mission planning software.

Their value to the Conservancy is that you can acquire near real-time geographic data, whether it be aerial imagery, Lidar, or water sampling in a semi-automated fashion that lends itself well to monitoring.

These aircraft vary from $3,000 DIY rigs with hacked point-and-shoot cameras zip tied to the UAV to quarter million dollar set-ups that support all kinds of features (including some we’d probably rather not know about).

On February 26, 2014 we tested the notion that a drone could be useful in this endeavor and flew some hardware that was definitely closer to the DIY range of the spectrum.

However it had a critical component: we outfitted the hexa-rotor UAV with a high resolution infrared (IR) camera. This would allow us to see a thermal signature of cranes settling down for the night. To date our pals over at USGS have been leading the way on testing the concept of counting cranes with UAVs. They flew fixed wing set-ups with integrated IR cameras and had positive results. We wanted to try and emulate their work, using commercial off-the-shelf gear.

We started out by doing a few test flights during the day to get a handle on two key questions: (1) would this flush the birds? and (2) was there enough resolution on the sensor to pick up individual animals?

Our ultimate goal was to fly a night mission, over water, with a pretty darn expensive camera, and in a way that would eliminate any risk of flushing a flock.

The results were stunning. This first video shows how much resolution we could get flying at about 50 meters; we were able to see individual American Coots, their black plumage radiating heat during the day and showing up bright white.

At night, we found that by taking off far-away (~500 meters) the cranes paid very little attention to what we were doing. Once at altitude the unit is barely audible and the visual clarity of individual sleeping Sandhill Cranes on the IR monitor was a beautiful sight that you can see in the second video.

At night the cranes actually show up cooler than the surrounding water because they are actually radiating less heat, keeping it trapped under their feathers to stay warm.

Since we didn’t know what the results of this test night flight would be, there were literally cheers and applause all around when we saw the images, not unexpected for a group of techie bird nerds.

From here it’s easy to extract a still from the videography; geo-referencing it is a little trickier but may not even be necessary if your were flying a set of regular transects at a known field location.

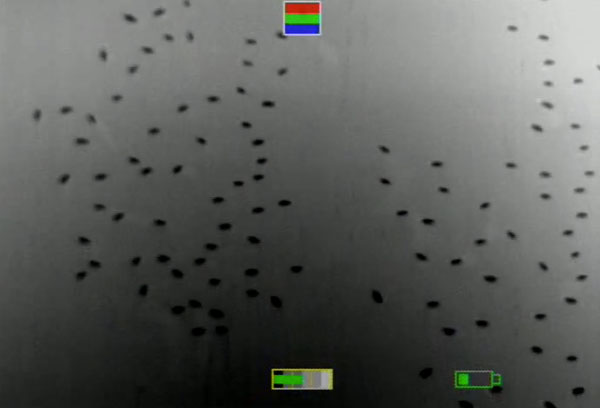

Cranes are a big bird and they are standing in water (a very uniform background surface), so creating automated ways to convert the image to count data was straightforward.

As we test these methods with other species and in other more visually complex landscapes, we will need to find robust ways to separate signal from noise. You can see our steps for turning the imagery into actual data just using some spatial statistics and processing on the geometry of each bird.

Accurate roost counts at Staten Island and other important sites for Sandhill Cranes throughout the Central Valley will be one of the most valuable ways to estimate the wintering population of this relatively rare bird.

More importantly, regular and accurate counts of roosting flocks help us to track how Sandhill Crane numbers are fluctuating in response to land management, climate or other environmental changes in this vast agricultural landscape. Only with this kind of information can we understand how cranes are doing and improve our strategies to ensure that this majestic bird persists in the long-term.

We are pretty sure UAVs will be as valuable to conservation as they will be in other sectors. There is a lot to figure out here, including privacy, safety, efficiency, and use of these data; the Conservancy will need partners to make the best use of these new tools. But the initial results are inspiring.

Yes, we can actually do something better than deliver your stuff from Amazon.

I recently found a Sandhill Crane’s nest in a wooded area behind our sub division that I caught on video with the air 2s. Beautiful animal. Have you seen any nesting areas while doing your research?

Hi. I see that drones, IR cameras, and birds are found together.

I have an application in the works…check out

conservationhaying.com

My Youtube which includes a method for georeferencing.

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=enWxSDKbFlM

Really enjoyed your article. Tom

USGS and USFWS have been working on this issue for a few years. For the area surveyed, counts from videography were very similar to ground counts. See http://rmgsc.cr.usgs.gov/uas/sandHillCraneProj.shtml

I’m a bit confused by the post. It seems to start out saying that counting birds is a challenge, then goes on to describe the use of UAVs in estimating bird numbers, but never compares the results of UAV counts to visual counts. Isn’t it required to compare the UAV counts to visual counts to assess whether the UAVs improve upon the existing methods? If so, then yes by all means use them as long as they don’t result in disturbance, mortality, etc., but if not, then what has been gained?

Hi Bob – Excellent question. This was only meant to be an experiment to determine if it is indeed possible to see these animals with IR imagery and the logistics involved. We are planning to run another set of flights in Fall 2014 concurrent with our existing “on the ground” monitoring whereby we will have the data to determine whether or not this is actually a better approach.

the true nature of conservation, in accordance to your mandate, to its explicit definition, is total protection and a no footprint.

in short, you might as well pack it in and return to the us where you belong.

we will be using drones in Manitoba, east escarpment, to show to what extent you do not protect the lands you purchased. we are requesting that the province remove all of your lands in the area. conservation is to be your only objective, not the use of lands for trails, public use, motor vehicles, damages, the encouragement of trespassing, cattle grazing, or any other ridiculous facade.

violations will be posted on you tube.

asta la vista (urban dictionary)

Very nice blog. Its really worth reading. Keep posting.