Many invasive species stories follow a similar narrative. When the non-native species first shows up, people either don’t notice it, or they don’t take the threat seriously. Suddenly, the invader explodes across the landscape, and conservationists spring into action. but so often, it’s too late.

That’s why invasive species success stories are so few and far between.

The Adirondacks is different. Here, over a huge landscape, the Conservancy and partners have excelled at a coordinated approach that’s making a difference: early detection and rapid response.

“Our team wakes up every morning thinking about invasive species and how we can stop them in the Adirondacks,” says Hilary Smith, director of the Adirondack Park Invasive Plant Program, a program hosted by the Conservancy involving state agency partners and dozens of other cooperators. “We started with an idea fifteen years ago, an idea that we could address this problem at a meaningful scale. Today, we’re a model program for the State of New York. We are seeing incredibly positive results.”

Invasives Problem, What Invasives Problem?

The first thing you notice traveling around the Adirondacks is its tremendous size: forest stretching as far as the eye can see, connected to expansive wetlands and wild rivers.

It’s huge. Six million acres of protected area, to be exact—larger than Yellowstone and Yosemite and the Grand Canyon combined. It’s one of the largest intact temperate forests in the world. That ecological health means that invasive species do not dominate here as they do in many ecosystems.

So what’s the problem? Why worry about species that are only located in small patches throughout a huge forest?

Beginning in the 1990s, conservationists realized those were the wrong questions to be asking. An assessment of the landscape revealed that some invasive plants were indeed taking hold and spreading into the forest.

“Conservationists and philanthropists have spent hundreds of millions of dollars in protecting lands and waters in the Adirondack Park over the past decades,” says Michael Carr, director of the Conservancy’s Adirondack Chapter. “It’s a huge investment in conservation. If you fail to address the threat of invasive species, you’re not fully respecting those contributions.”

Some of these invaders were particularly concerning. Take Japanese knotweed. In the United Kingdom, this non-native weed covers close to one-third of the country, costing millions annually to control. It not only chokes out streams; it can also grow through pavement and even weaken roads.

Or purple loosestrife: a flowery plant that thrives in moist areas, transforming once productive habitat into a monoculture of weeds. Given the 600,000 acres of wetlands in the Adirondacks, this plant offers mind-boggling potential to wreak ecological havoc.

“When we first recognized that invasives were making inroads to the region, we realized that we could catch infestations early, before they had a chance to spread, and that could make a huge difference,” says Smith. “We came to a realization. We can think big about this. Let’s use the best science and get the support of partner groups and local communities, and start to think and act as a region.”

The ecological intactness of the Adirondacks was the biggest ally in the effort. Conservancy staff realized they could focus efforts on key areas where there was a high opportunity for detecting invasive plant presence early, and an equally high opportunity for managing those small infestations successfully.

“We wanted a holistic approach that came at this challenge from every possible angle,” says Smith. “We’re thinking about every different aspect of invasive species work – prevention, detection, management, education, regulation. It’s integrated, and it’s coordinated. It’s also a model for dealing with the problem quickly and effectively.”

Detect and Respond

The Conservancy mapped the presence of invasives throughout the landscape and found that many infestations were quite small—covering fewer than .08 acres. This was good news. Very good news.

“One study showed that managers have the greatest chance in eliminating an invasive plant infestation when the infestation is fewer than 2.5 acres,” says Brendan Quirion, who heads the Conservancy’s Terrestrial Invasive Species Project in the Adirondacks. “It’s very exciting when we can transform an invaded site to one where native plants are recovering.”

In most parts of the country, such a goal would be unrealistic, or require huge investments in time and money.

As soon as we see a new plant, we dispatch the team.

Brendan Quirion

In the Adirondacks, though, early detection and rapid response means that invasives can be eliminated. When an infested site is located, the Terrestrial Regional Response Team – a group of contractors specializing in invasive species eradication – is called in and does a thorough removal effort. The site is carefully monitored for several years to make sure no invasives reappear.

As I drive around with Quirion, he routinely shifts effortlessly from telling an engaging outdoor story to noting a new invasive plant sprouting – often while driving fifty miles an hour.

“It changes the way you see things,” he says. “I’m constantly looking for invasives. And we have a lot of other people on the lookout. As soon as we see a new plant, we dispatch the team.”

It’s this rapid response approach that catches plant infestations before they become too big to eliminate.

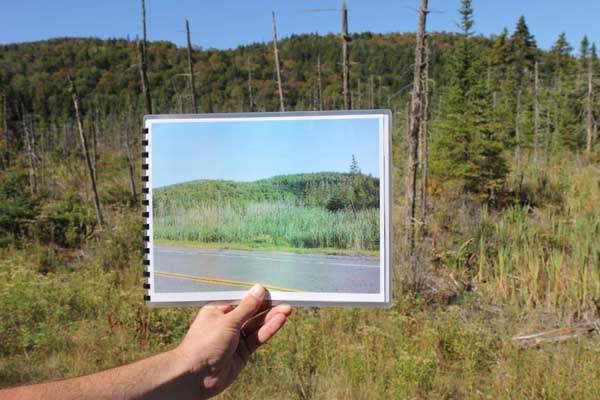

In the realm of invasive plant removal, the successes here are often stunning. Eradicating Phragmites, also known as common reed – another invasive plant that chokes out wetlands – is considered even in the scientific literature to be nothing more than the wildest of pipe dreams.

But here, of 131 Phragmites infestations treated, 37 percent already have had no Phragmites observed after only one year of treatment – results that have never before been recorded.

“We see opportunities and take action,” says Smith. “We are making progress in the region and the state is taking notice.”

It can be tough to maintain a sense of urgency for a threat that many people can’t see. But Conservancy scientists continue to recognize the threat that invasives could pose to wetlands, forest health and the area’s tourist economy. By continuing to map, detect and rapidly respond to plant infestations, they realize they can not only hold the line on invasives, but dramatically reduce the threat.

“When it comes to invasives, how do you measure success of what you don’t see? We hope that the invasives that you don’t see in the Adirondacks are a great indication that our approach is working,” says Smith. “When our response team returns to a site a year after detecting invasives, and those invasives are gone, it’s a notable success, and it gives us hope. We have to keep employing the best science, and maintain sufficient funding, so we can sustain those successes.”

The work of the Adirondack Park Invasive Plant Program is supported through funding from the NY State Department of Environmental Conservation. The Terrestrial Regional Response Team is a key strategy, made possible thanks to three years of private foundation funding.

how can ordinary citizens assist in eradicating invasive plants such as purple loosestrife in my area which is growing on private property?

Landowners can join together to manage invasive plants, like purple loosestrife, on adjacent private properties. In fact, a collaborative approach like this will likely result in more effective invasive species controls long term. The first step is to build awareness among landowners and municipal leaders about the problems invasive plants pose. You can then prioritize which species pose the greatest threat to what you are trying to protect whether it be native plants and wildlife, recreational values, aesthetics, etc. Knowing the distribution of the target plant in your area will help inform the appropriate level of response. It also helps to determine the likelihood of success of a control project since reintroduction from neighboring infestations should be avoided. Monitoring for new infestations as well as continued yearly monitoring/management of priority infestations will help you to achieve long-term control.

We recommend that resource managers and landowners use best management practices (BMPs) when controlling invasive species. BMPs are determined by the species biology, degree of infestation, geophysical setting of the infestation, etc.

For purple loosestrife, small infestations or individual plants can be controlled by digging up plants by the roots, prior to seed set, and disposing of the excavated plant material in contractor garbage bags. These full garbage bags should be left in the sun to bake for several weeks before they are brought to a landfill or transfer station for disposal. Never compost invasive plants as they may resprout. For larger infestations, herbicide treatments using glyphosate based products via foliar spray can be effective. Be sure to comply with all information found on the product label as well as any state/local regulations and permitting procedures before conducting an herbicide treatment. There are also biological control beetles available to control purple loosestrife. Contact your local environmental agency or extension program for management guidance specific to your area.

TNC’s Art Talsma is Idaho’s rapid response hero … an invasive species worst nightmare :-} Great piece as usual thanks for keeping the awareness and education going.

This is a great article (and program), but does not mention the problem of aquatic invasive species (AIS) in the Adirondacks. With so many boaters in the region, overland transport of AIS is a real threat to the ecology of freshwater systems, which have historically been disturbed through acidification from acid rain.

Sampling macrophyte communities in a number of Adirondack lakes this summer, there certainly are “hot spots” with abundance non-native macrophyte growth.

Andrew,

Great point! The Adirondack region is rich in water resources, too. This story features one aspect of important invasive species work underway in the region. The Adirondack Park Invasive Plant Program and its partners and volunteers are equally involved in aquatic invasive species prevention, education, detection, and response in lakes, ponds, and rivers. We’re working hard to address all invasive species threats to the region: aquatic invasive species, terrestrial invasive plants, and pests and pathogens. Time is of the essence. For more information, check out http://www.adkinvasives.com.

Thank you for raising awareness about aquatic invasive species.

Hilary Smith