Can small protected areas still deliver large benefits for both people and nature?

New research from Papua New Guinea demonstrates that locally managed marine areas effectively protect grouper spawning aggregations. And with modest expansions, these protected areas can greatly improve their conservation benefits.

Local Protection for Local Benefits

Known to the local community as manang, the brown-marbled grouper reigns king on the coral reefs of northeastern Papua New Guinea (PNG). Patterned in chocolate and white, these apex reef predators can reach lengths of 1 meter and weigh up to 10 kilograms.

“This species is very important for both commercial fisheries and the local community,” says Pete Waldie, a marine ecologist and PhD candidate at James Cook University’s ARC Centre of Excellence for Coral Reef Studies.

While an important food source, the grouper are also at risk of being overfished — they’re a long-lived, slow growing fish that takes years to reach sexual maturity. The species is currently listed as near threatened by the IUCN.

Just offshore of Dyual Island, in PNG’s New Ireland Province, more than a thousand grouper from three species gather each year between March and July to breed in what’s known as a fish spawning aggregation. To protect their resource and help curb overfishing, the local community, Leon, partnered with The Nature Conservancy to establish a small locally managed marine area, or LMMA, in 2004. Designated as a no-take zone, this 0.2 square kilometer patch of reef would allow the fish to breed undisturbed.

A 0.2 km2-protected area sounds absurdly small, especially when compared to the massive marine protected areas scattered across the world’s oceans. But marine conservation works a bit differently in Melanesia — bigger is not better. Communities in PNG own the land, reefs, and other natural resources adjacent to their traditional home, a system known as customary tenure. In many areas that ownership system is further broken down to different clans within the community, each having the obligation to care for their patch of reef exclusively. Small LMMAs — typically averaging around 1 km2 throughout Melanesia — match this tenure system and are widespread throughout the region.

“If a community owns 10 kilometers of reef and they protected all of their traditional fishing grounds people would starve, because there would be nowhere to go fishing,” explains Rick Hamilton, director of The Nature Conservancy’s Melanesia program.

The size of any community’s fishing grounds is also limited by manpower — Waldie says that 90 percent of the fishing is done with hand-carved dugout canoes, so fishing grounds are limited by how far someone can paddle in one day.

Previous research by Conservancy scientists showed that despite its small size, establishing the LMMA (known locally as Bolsurik) directly resulted in more grouper in the water. But was protecting the spawning aggregation site enough to ensure a healthy population and protect the grouper year-round?

Acoustic Telemetry, Spaghetti Tags, and Social Surveys

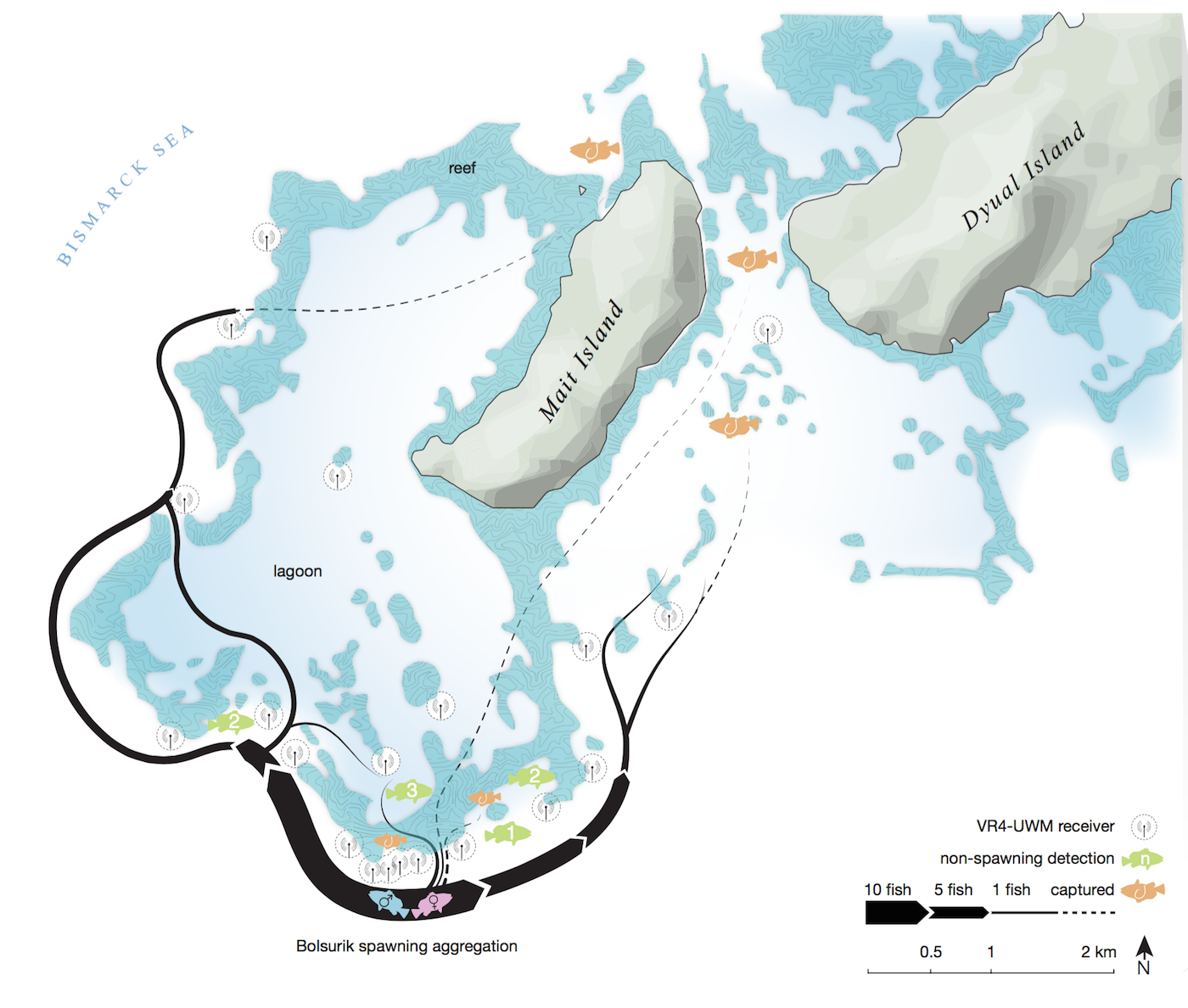

To answer these questions, Waldie and his colleagues used a combination of high-tech acoustic telemetry and low-tech tagging to figure out exactly where the grouper were during spawning and how far they dispersed in between aggregations.

With the help of the local community and Tapas Potuku, the Conservancy’s community conservation coordinator in New Ireland Province, Waldie captured 29 grouper in May and June of 2013. They surgically fitted each fish with a small acoustic transmitter. “It’s a small capsule and that sends out a coded ping,” says Waldie. “So seven beeps in a row that tells you ‘I am fish number seven.’” They also attached spaghetti tags — long strips of plastic coded with a phone number — so the fishermen could call in with the date and location if they caught any of the study fish.

Then Waldie and Potuku moored 20 acoustic receivers throughout the reef, anchoring them to the reef with stainless steel cables. Those receivers recorded each time a transmitter-equipped fish swam within approximately 100 meters. “Its like a piece of candy at the supermarket checkout,” explains Hamilton. “Every time the fish swims past the receiver it gets swiped.”

After two years, Waldie and his colleagues had enough data to understand how and where the grouper were moving in relation to the LMMA. Their results were published today in Royal Society Open Science.

“We found that the LMMA is doing exactly what it was set up to do,” says Waldie, protecting all of the tagged grouper during the week-long fish spawning aggregation. But they also found that all of the grouper left the LMMA during the non-spawning season, dispersing to the surrounding 16 km2 of reef and leaving them vulnerable to fishing or other outside threats for 90 percent of the year.

But the grouper didn’t go far — all stayed within 16 km2 of the LMMA and many dispersed no more than 1 or 2 km2. “So if we center protection around the spawning sites and expand the LMMA to a size of 1 to 2 km2 ,” says Waldie, “then we can protect a large proportion of the population year round.” He estimates that such an expansion would protect 30 to 50 percent of the fish during the non-spawning season.

Waldie and his colleagues also conducted social surveys as part of the research to better understand how the community felt about their LMMA. Potuku explains that fishers in the local community had differing opinions of the LMMA when it was first established. Now, the survey results show that a significant majority of community members felt the LMMA benefited their livelihoods, the community, and the environment. “The support of the local community is the only thing keeping these conservation efforts working,” says Waldie. With high levels of community support, a small expansion of the protected area is not out of the question.

“Hopefully other communities around New Ireland Province and PNG will use the management actions and approach taken by this community as a model they too can replicate within their marine tenure,” adds Potuku.

Beyond the Bolsurik LMMA, Waldie’s results bode well for the success of LMMAs throughout Melanesia. If the same limited-dispersal pattern holds true in other locations and for other species, then communities can significantly improve protection for their fish populations for a very small cost.

“The bigger, sexier western-style protected areas doesn’t work in areas where people are highly dependent on marine resources and have customary ownership,” says Hamilton. “Waldie’s results are further support for the concept that small LMMAs can have significant fisheries benefits, even for large species, if they are placed in the right location.”

Join the Discussion