Even when the fires are hundreds of miles away, they seem omnipresent.

It’s become part of our morning routine: Get up, pour a cup of coffee and check the air quality report. I live in Boise, Idaho, and smoky air is our reality. This July, with the Bootleg Fire raging across central Oregon, our city was in a constant haze. Even taking a short walk left my clothes smelling like I sat by a campfire, and my lungs gasping for breath.

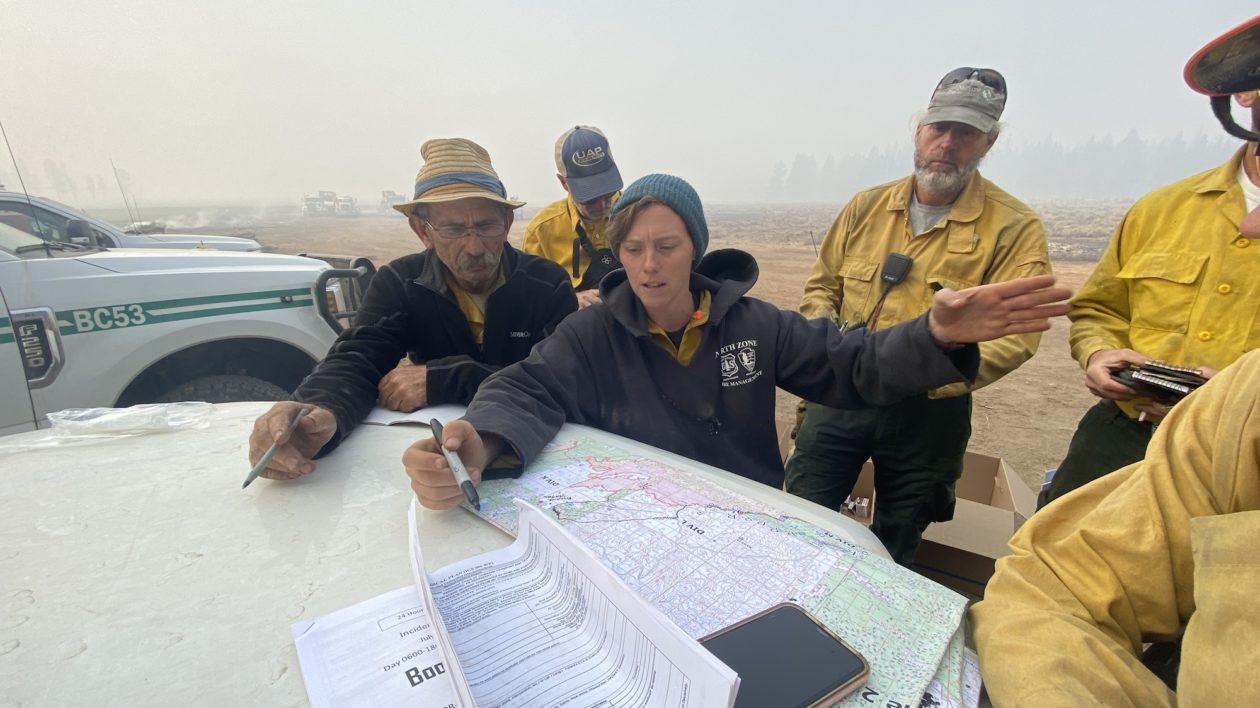

But 350 miles away, my colleague Katie Sauerbrey, The Nature Conservancy in Oregon’s fire program manager, dealt with the Bootleg Fire in a much more immediate manner. The fire had hit The Nature Conservancy’s Sycan Marsh Preserve. It threatened preserve facilities including an extensive research center.

If you talk to nearly anyone who is in the midst of a large wildfire, they’ll mention a significant level of chaos. This is especially true of a fire as big as Bootleg, which went on to scorch 414,00 acres, a fire so significant it created its own weather.

Despite that, Sauerbrey knew, deep down inside, she was prepared for this moment. Meticulously prepared. She had built the relationships. She had planned for such an event. Her phone was ringing with the right people coordinating the right way.

It’s become a familiar story for Nature Conservancy land managers. The Conservancy manages preserves and projects in a diversity of habitats around the globe. With increasingly hotter, drier conditions, many of those projects have now directly dealt with wildfires. The fires in the western United States dominate the headlines, and indeed many preserve managers and land managers there face this reality. But fires also affected Conservancy projects from Central America to Minnesota.

In 2020, 56 Conservancy preserves burned, a 195 percent increase over 2019. This year was similar, with dozens of preserves experiencing fire.

How does wildfire affect preserves? It’s a complicated answer. Through years of research, partnerships and field experience, Conservancy staff have learned lessons that can be applied more broadly. Because fire is never just about how it affects a property. These fires impact many people, even those living far from them.

Balance

It’s important to acknowledge that the majority of Conservancy preserves in North America were shaped by the frequent, widespread and sophisticated burning practices of Indigenous peoples and require some amount of fire to remain healthy.

Ecologically, wildfires aren’t necessarily bad. It depends on the conditions as well as a given preserve’s habitats, facilities, surrounding land ownership patterns and other attributes.

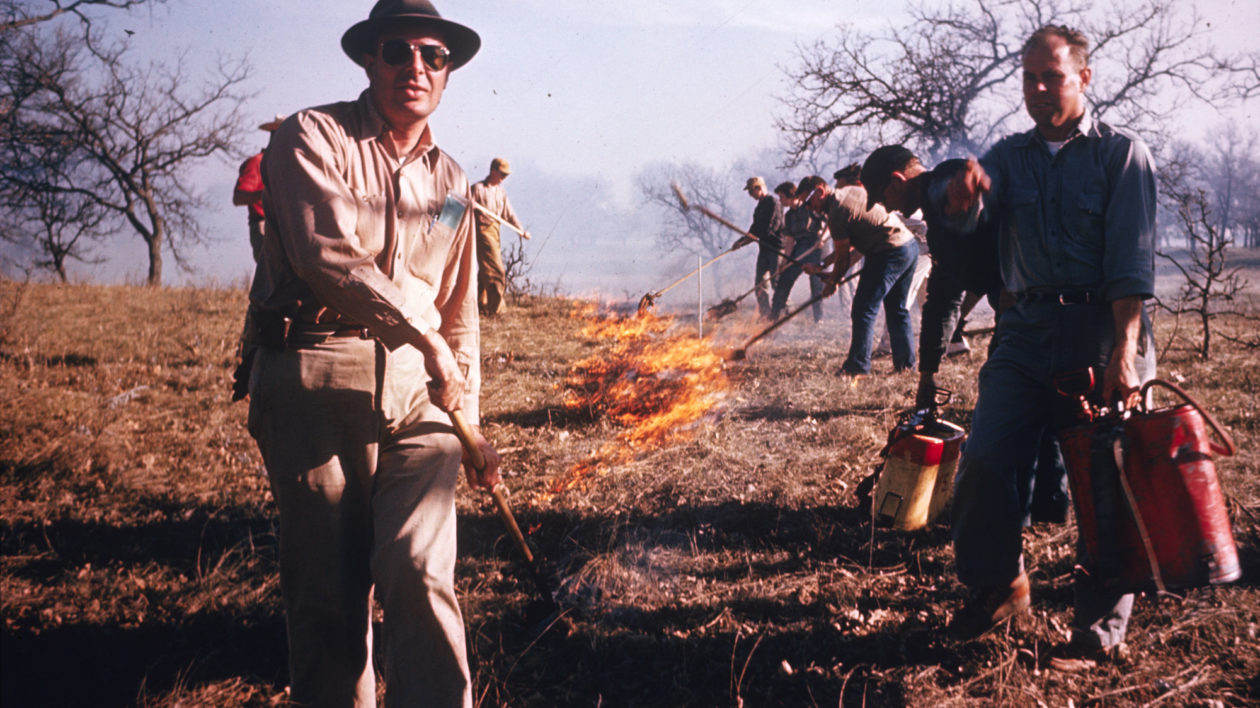

When it comes to fire, the Conservancy is known for its science, land stewardship and prescribed fire experience. This experience also provides opportunities to work with Indigenous peoples who continue to use fire in traditional ways and whose cultures depend on fire to persist. Through this experience, it became apparent that the accumulated fuels over the past 100-years coincided with the absence of Indigenous burning. Preceding the fire suppression era, people coexisted with fire, establishing an environment with variation in the occurrence, intensity, distribution and seasonality of fire.

Based on over 40-years of working with the Klamath Tribes, they sought their traditional ecological knowledge to guide and monitor new ways of thinking and managing their ancestral lands. Managers and scientists engage with Tribal members to provide opportunities to work with Indigenous peoples. The Conservancy manages Sycan Marsh in close coordination with the Klamath Tribes, who have stewarded that land for thousands of years.

In 2015 the Conservancy consulted a group of fire practitioners and cultural leaders in northern California and eventually launched the Indigenous Peoples Burning Network. Today the group includes 18 tribes in seven states that are revitalizing their traditional fire cultures in a modern context.

Be Prepared

This year, the fire season for The Nature Conservancy began early. Blane Heumann, director of fire management for the Conservancy, began dealing with fires in April, when the Belize Maya Forest experienced a wildfire at the same time as an exciting Earth Day announcement of protection of the area.

“This year, we had a lot of impacts to TNC preserves,” he says. “And each fire is a litmus test on how prepared we were.”

Fortunately, the Conservancy has the experience and the science to face this unprecedented challenge, honed over decades of managing fire on our lands. The organization conducted its first prescribed fire in 1962 and has burned more than 2.5 million acres of such burns on its properties to date. It has more than 400 fire-qualified staff and volunteers. Each of those burns requires a comprehensive prescribed burn plan and follows careful safety protocols.

“It has given us extensive and intensive experience with fire,” says Heumann. “We have decades of science work behind it. We understand how fire behaves and how to manage it. And we have stressed wildfire preparedness and wildfire safety for our staff.”

All preserves in wildfire prone areas must have fire safety plans in place. The plans include who needs to be called, who is on the property, evacuation protocol and how to report a fire. “First and foremost, we focus on protecting life and property,” says Heumann.

Fires also have ecological impacts, which can vary greatly across habitats. Like many fires, the one that affected a portion of the Belize Maya Forest project brought a mixed bag of impacts. The fire that burned area comprised of savanna habitat benefited from the burn but the moist tropical forest was severely damaged.

Prescribed burning and other methods of fuel reduction are part of the management plans for many preserves, and these can in some cases help lessen the severity of ecological impacts.

Eric Hoff is land steward for 27 preserves in Minnesota and the Dakotas. This spring, while driving home from firefighting training in North Dakota, he noticed an orange glow on the horizon. He knew immediately what that meant. “My first thought was it was a terrible, terrible night for a wildfire,” he says. “There were heavy winds, gusting up to 60 miles per hour.”

The fire burned more than 4,000 acres, including 175 acres of Brown Ranch Preserve. But the tallgrass prairie preserve is grazed and also has regular prescribed fire treatments. “If you have a regular prescribed fire program, it reduces the amount of fuel,” Hoff says. “Overall, this fire had pretty minimal impact ecologically. It was a really early season fire. It didn’t do any harm. It likely helped warm-season native grasses.”

Heumann notes other preserve fires can have similar outcomes. “Where we have proactively undertaken prescribed burning or other fuels reduction, we may well have a good outcome after a wildfire,” he says. “But one of the problems with the hot and drier climate in the western United States is the severity of the fires. They’re burning much hotter than ever.”

Fire on Sycan Marsh

What happens when a much larger, hotter fire hits a preserve? That’s exactly what happened at Oregon’s Sycan Marsh, a 30,000-acre haven for nesting and migrating birds and part of the Klamath Tribes’ territory.

The Bootleg Fire started on July 6 about 14 miles south of the preserve. Just four days later, it reached the property. “We were prepared for the moment it hit the property,” says Sauerbrey.

That preparedness took many forms. The majority of Oregon land management staff have and maintain firefighting qualifications. Fire plans are updated annually, including preparations for the property’s facilities. And she and other Conservancy staff have spent years building relationships with federal and state agency staff involved in fire management.

“We had built these relationships on the ground through prescribed burning,” Sauerbrey says. “Our staff know each other. We know each other’s skills. We were prepared so we could help bring out-of-town firefighters up to speed quickly.”

Sauerbrey emphasizes the importance of controlled burning, which has been undertaken at the preserve since 2002. “Having that experience and knowing how fire moves on the landscape made the wildfire’s behavior much less of a surprise. We burned here. Now we just had to shift to fire suppression.”

The controlled burning also helped mitigate the impacts of the fire. At one point, when the raging wildfire hit an area that had had prescribed burning, it immediately dropped down in severity. The Bootleg Fire ended up burning just under 12,000 acres of the preserve, with 4,000 of those acres forested.

“The marsh areas look beautiful now,” says Sauerbrey. “That’s an area that was meant to burn.”

In the forested areas, the post-fire condition largely depends on whether there were fuel reduction treatments like forest thinning and/or prescribed fire. “In some areas, it looked like a good prescribed fire went through,” Sauerbrey says.

Areas with no treatments didn’t fare as well. “I expect to see 90 percent morality on areas with no treatment,” Sauerbrey says. “It looks like a bunch of black toothpicks. The varying results present an opportunity for research, so we can continue to learn and adapt.”

Post-fire research has been important at Conservancy projects. This can help better prepare for future fires. And it potentially can help beyond preserve borders.

Beyond the Burn

Ed Smith started his forestry career in 1988 as an anti-logging activist. He even obtained a master’s degree in forestry so he could better support his advocacy with science. He didn’t want to see any remaining large trees cut. In 1996, his northern Arizona cabin was threatened by wildfire, setting off another round of inquiry and training – and this time, he reached a different conclusion.

“I went from anti-logging activist to a pro-management advocate,” says Smith, now senior fire ecologist and fire manager for The Nature Conservancy in California.

Smith knows fire is a natural part of the landscape. In fact, prior to 1849, fires lit by Native Americans and lightning burned 4.5 million to 12 million acres in California annually – a level that was almost reached in 2020’s record-breaking year.

“But the outcomes were vastly different,” he says. “Today there is too much accumulation of fuels due to fire suppression, the impacts of climate change and the reality of too many people living near highly flammable vegetation. Fire intensity has increased and so has the size of high-severity patches and their impact on watersheds.”

In 2020, fire impacted 22 Conservancy preserves in California, but Smith is also thinking beyond the preserve borders.

Smith has a passion for forest restoration and is working at landscape scale on various projects to influence fuels reduction and improve forest management. He says these efforts are largely possible due to the Conservancy’s long and direct investment in ecological forestry in the Sierra Nevada.

Smith notes that there is no one-size-fits-all fire management program. But as a report published by The Nature Conservancy in California notes, “Science shows that forest restoration – controlled burns and ecological thinning to remove small trees and brush that ignite fire – delivers a one-two punch, reducing the risk of megafires in fire-adapted conifer forests, like the Sierra, while allowing fire to be safely reintroduced with many ecological benefits.”

Smith is now working with partners to implement this ecological approach at the 28,000-acre French Meadows Project, while planning an order-of-magnitude larger North Yuba project two watersheds to the north at 275,000 acres. These projects use a collaborative, all-lands approach to restore forest health and resilience and reduce the risk of high-severity wildfire in the headwaters of the Middle Fork of the American River, and the North Fork of the Yuba River, critical municipal watersheds located on the Tahoe National Forest in California’s Sierra Nevada.

The approaches, including prescribed burning and forest thinning, are familiar tools used at Conservancy preserves around North America. That’s not coincidence. In fact, Smith believes there’s a direct link between the Conservancy’s history of fire management on preserves and the large-scale projects he’s helping develop.

“We have good ‘street cred’ among agencies because of 60 years’ worth of management on our preserves,” he says. “We have done a good job of using those sites as demonstration projects. It gives us a shared understanding of the issues, both ecological and social. It’s really important in gaining the support and instilling confidence among our partners. We have a no-nonsense reputation because we have worked on the ground. It can help us shape green forest restoration to create resilient watersheds.”

Thank you. We need to protect our wonderful forests.

I lived through the fear of a fire destroying my home. The Santiam Canyon, near Salem, Oregon, was horribly changed in huge areas by that fire in the Fall of 2020. I used a respirator to go outside and feed my livestock. The devastation has changed our world for my lifetime and the lifetime of many animals.

Thank you for helping to change the culture of stopping all fires. It makes sense, and you have proven it is true, that the indigenous people knew what to do and how to preserve and protect our forests. They are a good source of knowledge that needs to be listened to in all areas of our environment internationally. Thank you for proving their methods help save our forests, animals, plants, clean air, clean water . . .

Thank you for the work that you are doing.

Sarah Fogarty Luther – member

Nice complement to the interview with Jerry Franklin put on this week , mid April 2022, by Washington Native Plant Society. This old retired forester and Biswell/ Leopold graduate student, is happy to see prescribed fire beginning to be accepted.

There are some in California

Yeah right, prescribed burning like indigenous people did and “ecological” forest thinning. More like the numerous 80 acre clear cuts in my region with an adjacent National Forest calling for 100 acre ones. Rather disingenuous Nature Conservancy; the loss of trust on these “landscape scale” projects is no small thing.

Thank you, Matt, Ed, Blane and the fantastic fire teams at the Conservancy. This article is clear and “accessible” to those who have little context about fire in the American West and elsewhere. Matt, please pass my best wishes on to my old friends. Thanks.