Recently, I was warned by a backpacker on an Idaho wilderness trail that my family’s intended destination was overtaken by badgers. The man grimly reported that he had seen eight badgers just by his campsite.

We found the spot, exactly as he described it. But the meadow was home to a family of hoary marmots, not badgers.

Spending a lifetime in the outdoors, I’m used to wildlife misidentification. I am not talking about the problems associated with differentiating gulls or warblers – even many expert naturalists struggle with these. Nor am I talking about distinguishing shrew species, many of which can only be told apart from their dentition.

No, I’m talking about misidentifying common and/or iconic animals. Many of these errors involve animals that are large and at first glance seemingly unmistakable (like grizzly bears and mountain lions). Others are abundant in national parks, but also commonly confused (ground squirrels and prairie dogs).

For your reference, here is a field guide to commonly misidentified North American wildlife. I provide a brief overview as well as resources for more in-depth information. For space reasons, this edition will focus on mammals. If it proves useful to readers, I’ll post future “field guides” to misidentified snakes, fish, birds and other critters. Let me know in the comments.

The Ground Rules To Avoid Misidentification

You don’t have to be an expert to avoid the most common misidentifications. You can start by simply following these three ground rules.

If in doubt, you probably saw the least exciting option.

This may seem basic, but you’re more likely to see common animals than uncommon ones. Therefore, you have to rule out the most boring possibility first, before assuming you just saw something really awesome.

I hear a lot of sightings where people “think” they saw something really cool – say a mountain lion or a wolf – in an extremely unlikely area. Then it turns out they had a quick look or were in thick forest. If you see a wild canine running across a field outside Denver, it’s most likely not a wolf but a coyote (or a German shepherd).

Beware “barstool biologists.”

Walk into nearly any bar in rural America, and you’re likely to hear some version of: “The state biologists spend all their time in front of computers. I’m out there in the woods, and I know there are lots of cougars (or whatever) in these woods.”

Some colleagues call these folks “barstool biologists.” Know how to find reliable sources of information (this applies to other aspect of life as well). The slightly inebriated guy who tells you about the black panther his cousin’s friend’s coworker’s niece saw in suburban Rhode Island is not a great resource for wildlife ID. I sincerely hope I didn’t have to tell you that, but judging by some wildlife reports I see, it is worth noting.

Field guides and nature apps are your friend.

There is a wealth of great information out there. A field guide is money well spent before any national park vacation. These are written and illustrated by experts and will not only help with common wildlife, but also help open your eyes to other wonders of the natural world.

Many fine apps exist that can also aid in identification, and also help you report sightings (which can be corrected if necessary by skilled naturalists). There are field guides and apps for nearly every possible nature sighting. Using them adds immeasurable enjoyment to your time outdoors.

With that in mind, let’s go over some of the most commonly misidentified wildlife in North America.

Black Bear or Grizzly?

Everyone traveling to Yellowstone or Glacier wants to see a bear. But what bear is it?

The most common reason for misidentification lies with this fact: Not all black bears are black. They come in a variety of colors including brown and cinnamon, both of which can look like grizzlies. Further, black bears are more likely to be brown in areas with grizzlies. So color is not a reliable way to tell species apart.

The first thing to do is to look for a hump. Grizzlies have humps; black bears do not.

Black bears also have a face with a nose that slopes straight down, somewhat like a dog. A brown bear’s face is concave or “dished.” It looks more, well, like a bear face. Finally, look at the ears. The black bear has tall, pointy ears compared to the grizzly’s rounded, less conspicuous ones.

Get Bear Smart has an excellent guide on bear identification and a quick search will yield many other resources, including fun photo tests to try your ID skills.

Mountain Lion or Bobcat?

This one is easy: look at the tail. A mountain lion’s tail is long; the bobcat’s is short. That should immediately rule out the possibility of most misidentification. The mountain lion is also very large, weighing as much as 150 pounds. A bobcat tops out around 35 pounds. Bobcats also tend to have spots.

One challenge can come with trail cameras, as the images can be less-than-clear and it may be difficult to tell scale. There is a social media hashtag #CougarOrNot run by experts that can help. Reviewing that site can help you tell the difference.

Mountain lion sightings are rampant in the eastern United States, but scat, trail camera photos, kill sites and other evidence is lacking. If you think you’ve seen a mountain lion in the East, first refer to Rule #1 in this blog. A lot of sightings are in thick woods, or at night. And lot of “mountain lions” turn out to be thin bears, dogs, or coyotes.

In some areas, bobcats can be confused with the similar-looking but much rarer lynx. Here’s a good resource for telling the difference.

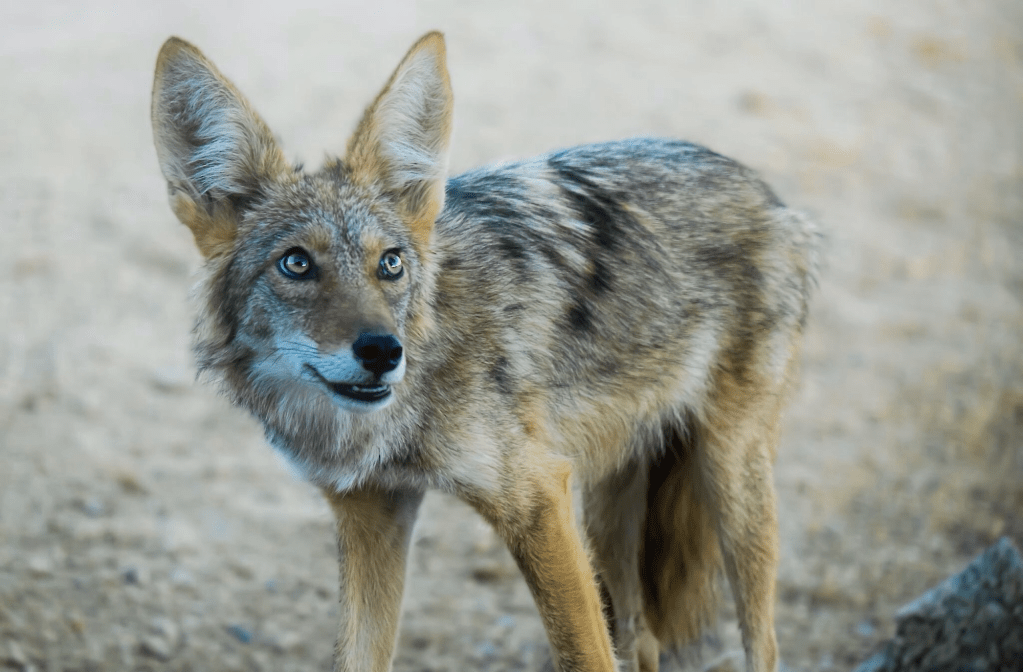

Wolf or Coyote?

Telling wild canines apart in the wild can be tough. A wolf is much bigger, which doesn’t help if you’ve never seen a coyote. The wolf’s face is broader and ears more rounded than the coyote’s narrow face and pointy ears. The California Department of Fish and Wildlife has an excellent page that breaks down differences in appearance, vocalizations and tracks.

Understanding habits is an important part of wildlife identification. Coyotes are very adaptable and can be found in agricultural areas, suburbs and even cities.

In the Midwest and eastern United States, canine identification gets confusing. Red wolves are very difficult to tell from coyotes (and red wolves are also very rare). This is compounded by the fact that eastern coyotes actually contain eastern wolf genetics. And there is an eastern wolf that lives in parts of Canada. Clear? My previous article on wolf hybrids breaks this down for you. Any mammal field guide and a basic knowledge of range and habits can help you make the most educated ID.

About That Badger

A badger is a distinct looking creature, but many people find mid-sized mammals confusing. For badgers, look for the black-and-white face and long claws. It digs ground squirrels out of their burrows, so it is powerfully built.

A marmot is the western version of the woodchuck. It’s an herbivore and lacks the pointy snout and stout claws of a badger.

In recent years, fishers have been reintroduced in the eastern United States and are thriving. But many folks are unfamiliar with them. If you picture a large, furry weasel, you will get the right idea. Wolverines are very rare and hard to see, and are not found in the eastern US.

Martens have similar tracks to fishers and favor the same big woods habitat. But they are smaller, redder, more streamlined and have two noticeable black lines that go from the top of their eyes to their forehead. ProTrails will help you distinguish these cool animals: and count yourself as lucky if you see them!

Chipmunk or Golden-Mantled Ground Squirrel?

Chipmunks are common backyard animals in many parts of North America. When people camp or picnic in the West, they often remark on the obese, super-sized chipmunk mooching snacks. Except it’s not a chipmunk. It’s a golden-mantled ground squirrel.

I hear this misidentification every year. It’s easy to avoid. If you see a gigantic chipmunk (double or triple the size): it’s the similarly striped golden-mantled ground squirrel. And like chipmunks, it loves to hang out anywhere it can pilfer food from outdoor recreationists.

If you really want to put your wildlife identification skills to the test, by the way, try Western US chipmunks. In most places east of the Rockies, there is one species, the Eastern chipmunk. From the Rockies west, there are 23. Identifying them can test even skilled mammal enthusiasts but it’s a worthy challenge, as the species are active in the daytime and fairly easy to locate.

Many have striking differences. A chipmunk quest to see all the species would take you to varied habitats in some of the continent’s most spectacular places, from the Olypmic Peninsula to the Redwoods to Joshua Tree to Arches and beyond.

Prairie Dog or Ground Squirrel?

“Look at the cute prairie dog!”

It’s a proclamation I have heard at the Grand Canyon, the Yellowstone Geyser Basins, and on Idaho’s sagebrush flats. In all instances, the “prairie dogs” were actually ground squirrels. This is an easy mistake to make. They look similar. Prairie dogs prefer grasslands and live in large colonies. Ground squirrels (usually) live in smaller colonies and can be found in a wider range of habitats.

There are several species of prairie dogs and multiple species of ground squirrels. These are common animals to see on the classic Western US road trips. They also exhibit quite fascinating behaviors.

If you’re interested in learning more, I highly suggest Tamara Hartson’s field guide Squirrels of the West. It’s compact and will aid you in identifying not only ground squirrels and prairie dogs, but also marmots, tree squirrels and chipmunks.

These small mammals need our help as they are heavily persecuted and unappreciated. Learning a bit about them can assist in their conservation.

Finally, You Never Know…

I’m sorry to say that it was probably a bobcat in your neighborhood, not a cougar. But you never know. Learning a bit about wildlife identification can actually help you know when you really do see something special.

When a mountain lion went on walkabout from South Dakota to Connecticut, with many stops along the way, many initial observations with discounted. This is because there are so many fake lion sightings that no one could believe there were real ones. (I highly recommend Will Stolzenburg’s Heart of a Lion for a compelling account of this animal).

A wolverine lived in the wild for several years in Michigan (it was a zoo escapee, but it really was a wolverine). Weird things turn up in weird places.

Unfortunately, as with the fairy tale, people who cry wolf (or mountain lion, or wolverine, or bigfoot…) don’t help. They cause biologists and other experts to discount sightings because they’re so used to the unreliable ones.

Carry a field guide, rule out other possibilities and report your cool sightings. You’ll be helping conservation and citizen science – and have fun doing it.

Due to limited space, I can’t list all confusing wildlife identifications. If you have questions about a creature you’ve seen, describe it in the comments and I’ll do my best to help.

I have been studying flora species for quite some time. I also get stumped at the shear volume of incompatible information when it comes to tangible knowledge on micro variations on specific species. Those micro variations or ‘mutations’ have caused many mishaps in misidentification in a variety of species. This is also why mushroom field guides are so difficult to interpret. Mushrooms always look so different and mimicry is so prevelant in these specimens. That being said, atleast if I misidentify a mushroom, a flower, a tree, or the like, there is near no risk associated (unless consumed or absorbed), this same thing cannot be said about fauna. Mistake an eastern foxsnake for a massassaga rattle snake, and that’ll be the last mistake you ever make.

Since the 1979, I’ve been disappointing the excited reporters of “observed” rarities, so I loved your endorsement of the “boring” option.

Upper Florida Keys residents tend to assume every rat they see is a federally endangered Key Largo woodrat. Unfortunately, Old World (Rattus) rats are far more common, more widespread, and highly variable in color. I usually observe them in the hand (or trap), where the rats become much easier to distinguish from a glimpse in the forest. But, if it wasn’t in forest, and if it wasn’t NORTH Key Largo, it wasn’t a woodrat. Between free-roaming domestic cats and introduced Burmese pythons, woodrats are only barely hanging on, even in the ten miles long strip of habitat set aside for their preservation.

Also, not every colorful snake is a coral snake, nor is every small rattle snake a “pygmy” rattler… even diamondback rattle snakes have babies! And, by the way, so do goliath groupers.

America’s economic success (and absence of effective regulation) has fueled a sustained boom in the trade of ornamental wildlife and wildlife as pets (servals?!), especially among collectors of birds and reptiles. So, I was not very surprised to encounter Australian black swans, African savannah monitors, a New Mexican gray-banded king snake, and various parrots (from almost everywhere but here) roaming about Key Largo.

When I recently traveled to Cape May County (NJ), someone brought me an observation of “voles” in their yard and barn. That struck me as bizarrely specific, given the number of possible alternatives, and the reporter’s lack of training in wildlife biology. If my recent retirement and now-idle Sherman traps allow, I might

enjoy looking into this one.

Twice I have seen a dark furry animal about 20 in long without a tail and 4-6 in tall that moves almost cocoon like with very little distinguishable tail if any

Have no idea what it could be

It was seen moving next to condo near dunes in st Augustine Florida

Any ideas?

I saw a small mammal swimming in an urban lake. I have seen both muskrats and minks in the area (Minneapolis). Defining behavior was that it was sticking its tail straight out of the water. At first, I thought it was a stick with a turtle on the underwater end, moving it around. Eventually, the rest of the animal emerged, swimming and diving around in a milfoil patch. No vegetation in its mouth that I could see. Small, slender and brown, it reminded me of a long, skinny chipmunk with a thick, dark tail, which it often stuck straight out of the water. Any idea what it was?

The mostly like candidate would be a mink. This guide may also help you narrow it down: https://blog.nature.org/2021/04/12/beaver-otter-muskrat-a-field-guide-to-freshwater-mammals/

Are mountain beavers real? And have you ever seen one?

Hi Amanda,

Yes, mountain beavers ((Aplodontia rufa) are indeed real, although they are not beavers nor are they closely related to beavers.

The mountain beaver (also known as a sewellel) is an interesting creature. It is the only surviving member of its genus and is what some call a “living fossil.” They need to live near water. They are not uncommon in the Pacific Northwest, although they are somewhat challenging to see. I have never seen one. I have thought this creature would be interesting to write about in a future Cool Green Science post. Good to know there is interest. Thanks for your question.

Matt Miller

Cool Green Science editor

Thank you for this helpful and interesting discussion about differences between animals. Especially thanks for the photos! Benita Smith

Good article. Here in north central Texas, bobcats and coyotes are seen frequently in urban areas. The animals that are frequently misidentified here are nutria, beaver and muskrats. I am fairly certain that I have never seen a muskrat; nutria, however, have become all too common in city parks and nature preserves alike. I would be interested in seeing more articles like this. As an avid nature photographer, I always try to identify the correct genus and species before posting.

Thank you. I find myself not getting into arguments with armchair experts. I give correct data and if I don’t know what something is, I research it. Just the other day I said “chipmunk” but the property owner said: “ground squirrel.” Not so, but it’s exhausting to argue . I was lucky enough to have Mel Ellis for a dad, so that gave me a leg up.

This article accomplished its purpose. The photographs and information gave enough detail, but not too much to help. If I would have read this before my trip to the Canadian Rockies I would have seemed smarter. The ground rules are spot on.

Great article. I learned several things that hopefully will be useful. Thanks.