The mouse moves from its burrow, searching and sniffing nervously for any predator. The nighttime meadow is still. Nothing flies in the air above. All is clear. Or so it seems.

The mouse slightly relaxes as it feeds. It cannot see the pale form outstretched on a nearby tree branch. Watching. Waiting.

When the pale form pushes off the branch and into the sky, the mouse hardly notices. The ghostly form flies quickly over the grass, honing in on its oblivious prey. Too late, the mouse notices a ghostly form, and begins a mad dash towards the burrow. But the pale predator lands on top of the rodent. The mouse is held by two soft, velvety capes, firm but gentle. As if it is being hugged.

Unfortunately for the mouse, this is a horror movie embrace. As it begins to struggle, the rodent feels powerful, sharp incisors clamp down on its neck, again and again. As it squeaks and makes one last push for freedom, a final bite clamps down on its head, crushing the skull to pieces.

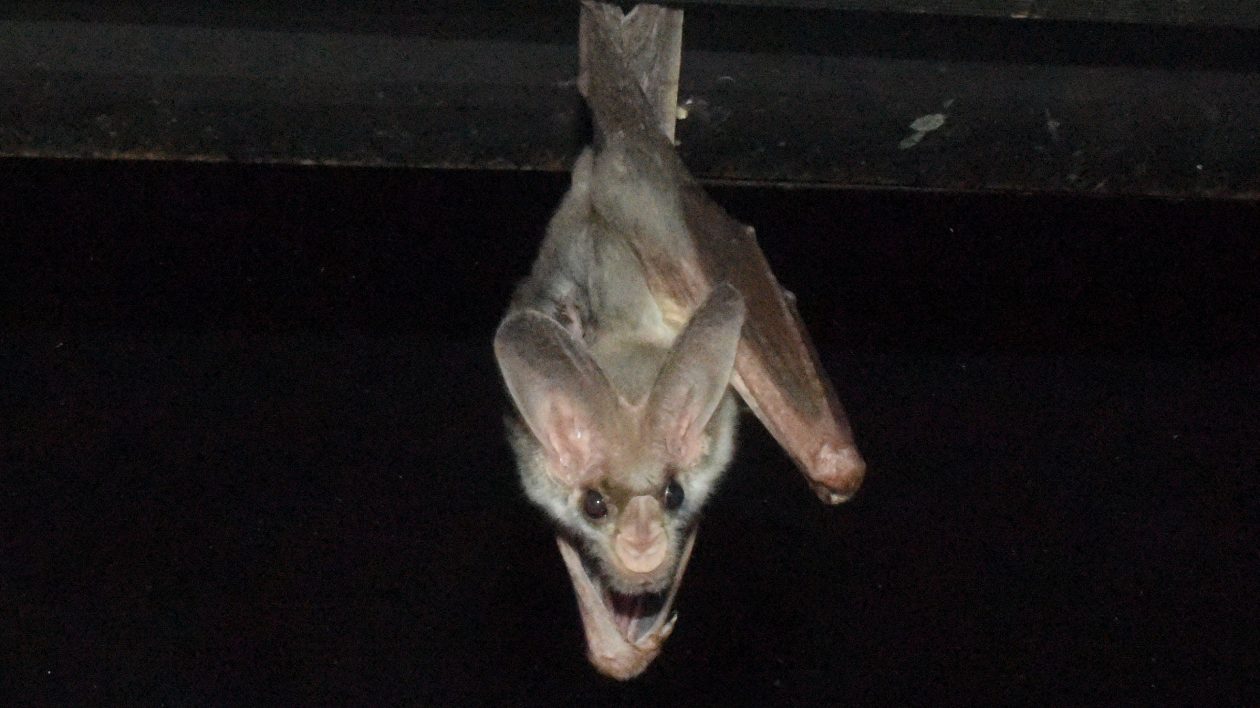

The rodent had succumbed to one of the world’s most effective and coolest predators, the ghost bat.

A False Vampire

When Halloween thoughts turn to bats, most people picture small, black flying mammals. Most think of bats as rather uniform creatures, all more or less looking the same. In reality, there are more than 1,300 bat species worldwide, and they exhibit a fascinating diversity in appearance, size, behavior and habits.

There is a bat that has a wingspan of 6 feet, and one so small that people call it a “bumblebee.” There are white bats and bats that fish and bats that help make your tequila.

And there are bats that even hunt small rodents and birds, like the ghost bat. Only one percent of the world’s bats feed on vertebrate prey. These bats also highly secretive – so secretive that people only relatively recently realized they were hunters and not blood feeders.

Ghost bats belong to a group of bats known as false vampires. “False vampire bat” is a term applied to five genera of bats found in Asia, Africa, Australia and Central and South America. Due to their large size and sharp teeth, early observers assumed they made incisions and fed on blood, like the famous vampire bat.

Conventional wisdom often suggests that people are less connected to nature in modern times, but in reality a lot of early nature knowledge – allegedly built on observation and living closely with wildlife – turns out to be pure nonsense.

Ghost bats and other false vampires do not feed on blood. They hunt and eat large invertebrates, lizards, birds, rodents and even other bats.

Ghost bats were once found over a large swath of Australia, but they have disappeared from the interior of the country. They are now restricted to the tropical north. At around five inches long, ghost bats are the largest bat in the suborder Microchiroptera, also known as the microbats. They are the only carnivorous bat in Australia.

Their coloration varies, but many have a beautiful pale coat. In flight, this makes them appear like – you guessed it – ghosts.

Hunting with the Ghost

Ghost bats are among the world’s most intriguing hunters. Insectivorous bats are well known for their use of echolocation. Bats send out sound waves from their mouth or nose. These waves bounce off objects in their path, like mosquitoes, and the echo returns to the bat’s ears. Bats can then hone in and find prey, even in complete darkness.

Ghost bats use echolocation to find prey, but not all the time. Instead they employ a variety of hunting techniques. They often will perch on a tree, as described in the opening of this blog. They have large eyes, and they scan the grass below for prey.

When the prey is located, they fly and attack, landing on the animal and wrapping it in its wings. The ghost bat then delivers lethal bites to the head and neck. They devour just about everything, including fur, feathers, bones and the chitinous exoskeleton of insects. According to one source, ghost bats “appear to need this roughage in their diet because if they are fed on boneless meat in captivity they soon become distressed and fouled with loose excreta.”

Ghost bats also have large ears, enabling them to listen for small animals scurrying around below. This suite of hunting tactics makes them effective predators. This also understandably leads to people labeling them as ferocious. But bat researchers have found that false vampire bats are often gentle and protective of each other.

Bat researcher and accomplished conservationist Merlin Tuttle spent a lot of time observing other species of false vampire bats. As reported in Bats Magazine:

There was a surprising gentleness, however, displayed by both the male and female of this breeding pair. Both were exceptionally solicitous of their young. The male was observed bringing food to the female and wrapping his large wings around both mother and pup. Observations in the wild also suggest that the adults, both male and female, may take turns guarding the young at the roost while their mate goes out to hunt, returning with food to share.

Bats and Barbed Wire

Echolocation enables bats to easily maneuver around a variety of hazards; biologists note that they can detect obstructions as thin as human hair. Since ghost bats don’t often use echolocation, they don’t detect obstructions. They hunt close to the ground in meadows and woodlands, and their sight allows them to navigate through trees.

But they don’t detect a new obstacle: barbed-wire fences. Flying swiftly after prey, the bat can dart right into the fence, and become impaled. It’s a significant threat to the species, but not the only one.

Ghost bats have been in long-term decline, according to the Australian Wildlife Conservancy. The species is highly susceptible to human disturbance, as is true with many bats around the globe. People encroaching on caves and mining have helped eliminate bats throughout much of their range.

Australia is well known for its invasive predators, including foxes, cats and cane toads. While these animals do not hunt ghost bats, they do feed on the same prey as the bats. The impact of these non-native species on bats is not really known, but it’s almost certainly not helping.

The good news for all bat species is that more people appreciate these fascinating and ecologically important. No longer are they just the stuff of Halloween nightmares. October is now also officially Bat Appreciation Month, a time to celebrate the diversity of bats…the pollinators, the mosquito controllers and the fierce ghosts of the Australian skies.

I didn’t know about October being Bat Appreciation Month until reading this blog. What a good idea!

On a sad note, I’ve heard that evidence of white nose disease has been found in the bat colony at Carlsbad Caverns. I’d hoped that the Mexican free-tailed bats there might be isolated enough there to not catch it. But given how far bats can travel during their nightly forays, that shouldn’t really be surprising.

Please, for the sake of all bats, can we stop using horror type language and depictions or descriptions. Yes, this species is an efficient hunter, but was it necessary to describe the repeated biting the neck and crushing the skull? No matter what you say after all of that, what people who do not love bats remember is the association with

horror, halloween, and negative images involving vampires. Perhaps the readership of this site will be more enlightened about bats but predation in most forms in nature is not pretty. The article would have been just as interesting without the sensationalized beginning. Bats are maligned enough, please think again about the type of language used to describe bats. Fear of bats has led to

horrific acts of violence wiping out entire colonies in the thousands.

I have been fascinated by bats for years. It is very discouraging that many people do not understand the role of this mammal. I teach my students in class the role of animals in nature and hope they grow up to realize the importance of saving as many species as we can. All animals have a mission and hope many more can be saved and not senselessly pushed further toward their extinction and will quickly lead to ours.

Thanks for sharing this. About 65 yrs ago when I was in high school I belonged to the Splunkers Club. One weekend as I was wiggling on my belly out of a cave, I looked up and saw a bat with a pig face and one with a mule face. I fell in love and picked them off the ceiling and put one in each pocket of my flannel shirt and took them home to my parents basement. I did realize my dad had pet spiders in his basement work shop and he would catch insects and call his spiders and they would come and he would hand feed them. He also had a very little salamander running around. Well my bats proceeded to eat his spiders and his mini salamander, dad got so mad he threw my pet bats out the back door and I never saw Muley Bates or Oscar Piggy Bates again. I was sad.

Don’t you mean “vertebrates” below?

“They hunt and eat large invertebrates, lizards, birds, rodents and even other bats.”

They do eat large invertebrates in addition to vertebrate prey like rodents and birds.

What a great read. Appreciate learning about all the bats!

Thank you, Matt, for your article on the ghost bats of Australia that I had never heard of before. Thanks for getting the word out of how we need them as everything in nature has a niche to fill and a reason to be here! I love bats! One summer in Sonoma CA, we saw a bat making many swoops over the pool to scoop up water for a drink!

Fascinating, I appreciate all wild life. Thank you for all this information. I lived in Australia for ten years and was intrigued by the amazing fauna. This takes it to a higher level.

Karen

Fascinating! All new information to me. Great article.