The women huddle over the sea turtle, whispering quietly in Solomon pidgin. They have lived their entire lives just a short boat ride away from these islands, which are the largest hawksbill sea turtle rookery in the South Pacific. But for many of these women this is the first nesting hawksbill turtle they’ve ever seen.

And most of them had never even visited the Arnavon Islands, where their communities have led conservation efforts to protect this endangered species for more than 20 years.

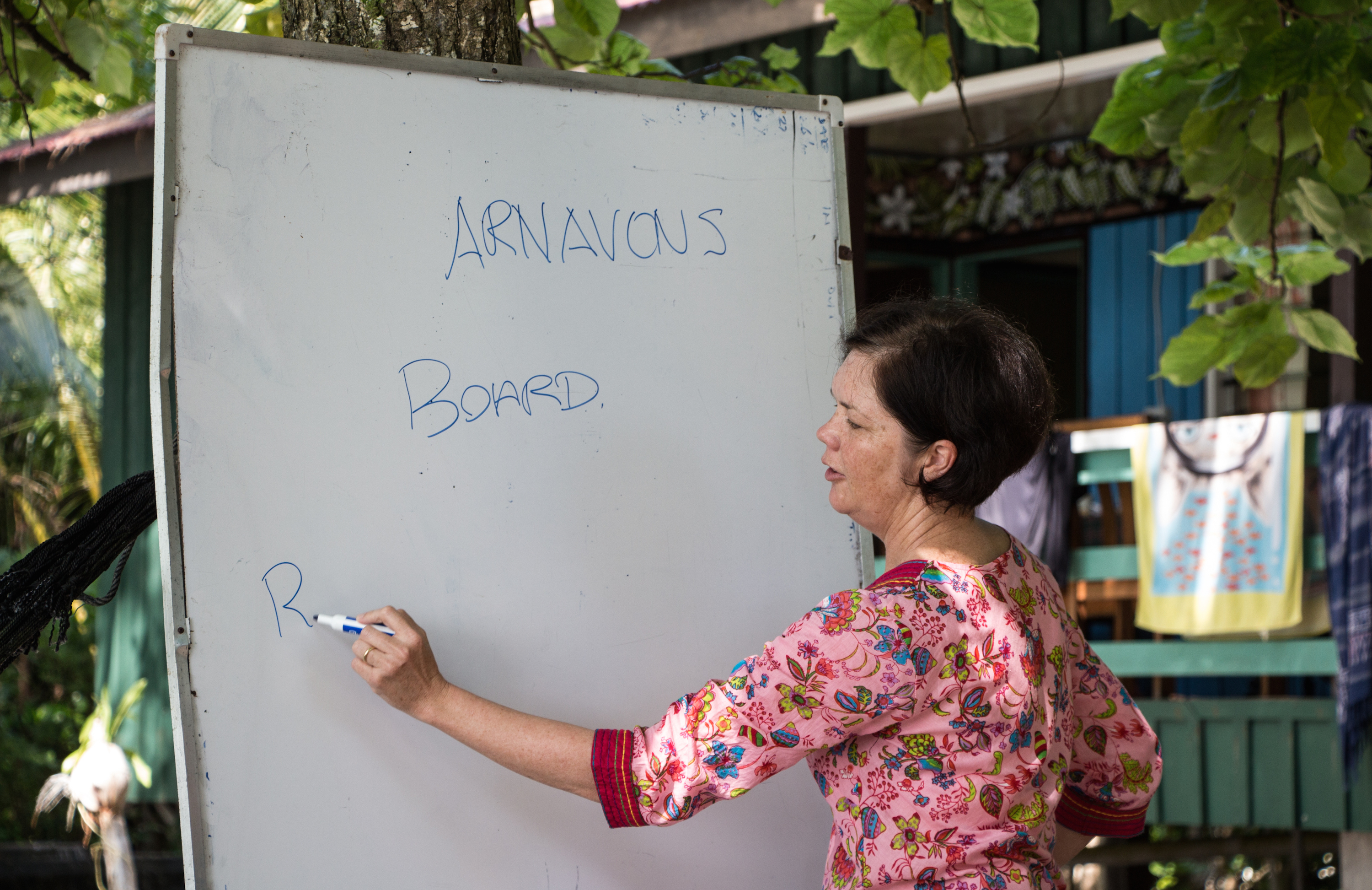

Research demonstrates that involving more women in community conservation projects is key to their success, but without conscious effort they aren’t always included. So Nature Conservancy scientist Robyn James is changing the way conservation projects in Melanesia incorporate women — and using her experience to develop gender-inclusive conservation strategy and policy recommendations for the entire organization.

The Difference Between Sex and Gender

Though the words are often used interchangeably, sex and gender are not the same thing.

Sex refers to the biological differences between males and females. For example, only male voices drop with puberty while only females can become pregnant. But gender refers to the cultural differences between men and women, differences not imposed by biology but by societal expectations. The stereotypes/expectations that women are better home-makers or that men shouldn’t cry are rooted in what society expects.

And as it turns out, how culture dictates gender roles is a significant issue for conservation. Specifically, community conservation often takes place largely without women, and that’s not a good thing.

“Conservation and science are male-dominated professions,” says Robyn James, the Conservancy’s conservation director for Melanesia. “I want to get women more involved in our work, both in the local communities we work with in these two countries and in our Melanesian staff.”

Traditional Melanesian gender roles dictate that men are the head of households and decision makers, while women are caretakers of the home, raising the family and providing food. These gender differences result in a massive disparity of education and opportunity for women, further adding to the challenge of bringing them into local conservation projects. In the Solomon Islands, less than 17 percent of women finish secondary school and 80 percent of women do not have access to a bank account, which prevents them from holding and saving money.

“Before we worked with TNC, women were neglected,” says Moira Dasipio, one of the few female chiefs from Isabel province. “Women didn’t have a strong voice in decision making around our natural resources; we were just left in the kitchens and there we would stay.”

And without women, conservation efforts will never truly thrive.

Women didn’t have a strong voice in decision making around our natural resources; we were just left in the kitchens and there we would stay.

Moira Dasipio

Founding KAWAKI: Katupika, Wagina, & Kia

A participant in the Conservancy’s Science Impact Project (SIP) James is incorporating gender equity into both conservation in Melanesia and across the organization. As part of SIP, James will focus on incorporating women into on-the-ground conservation programs in Papua New Guinea and the Solomon Islands. Those efforts will inform both a gender strategy for the Melanesia program and policy direction for all of the Conservancy.

“It sounds simple, but if we’re not consciously working to include women in conservation and natural resource management then only the most powerful or dominant demographic will be represented,” says James. “And in many cases, including in Melanesia, that’s men.”

The KAWAKI women’s group is part of James’ work in the Solomon Islands, specifically the Arnavons Community Marine Conservation Area (ACMCA), which protects the South Pacific’s largest hawksbill sea turtle rookery.

More than two decades ago, the provincial governments of Isabel and Choiseul, the Conservancy, and leaders from three local communities came together to create a protected area around the Arnavon Islands to protect the island’s value as a cultural site and critical rookery for endangered hawksbills. But both the ACMCA board and the conservation rangers who run the turtle monitoring program on the islands were historically all male.

“The story has always been that the Arnavons is a cultural place for men, not women,” says James. Many women from the communities have never been to the Arnavons, and many were unaware of the details of the two decades of ongoing conservation efforts. Involving women would strengthen the conservation ethic within the communities, something that is necessary given that poaching does still occur within the protected area.

The idea for KAWAKI was born when Marilyn Gedi, a resident of the Kia community and the Solomon Island’s first female police officer, approached James with the idea of forming a women’s group dedicated to conservation awareness for the Arnavons.

“Where this is conservation there should be both [men and women],” says Gedi. “We need participation from the other villages so that they feel like they own the island and have some respect and pride for it.”

“Gather round, KAWAKI! Gather round!” yelled Dasipio across the Kerehikapa field station. During their two days on the Arnavons, the nine founding members of KAWAKI met to draft their vision for the group and concrete next steps. Now they were ready to share their efforts.

Our turtle tagging crew, conservancy staff, and ACMCA rangers all sat on the beach to listen as each woman took turn a reading aloud the vision of KAWAKI: to unite women from Kia, Wagina, and Katupika; to celebrate community conservation and our culture; to raise awareness about the importance of Arnavons; to build better futures for our families; and to promote sustainable marine resource management.

In addition to their shared goals, the KAWAKI women also created a plan for their first major effort — raising awareness in each of their communities about conservation efforts in the Arnavons with the aid of a custom-made awareness kit. “These women they really want their kids to grow up with a conservation ethic,” says James, “so the next generation understands how to manage their resources sustainably.”

Previous conservation efforts have benefitted greatly from similar awareness efforts targeted at adults. The Conservancy partnered with Mother’s Union — a women’s group associated with the Anglican church — to spread awareness about the Conservancy’s Ridges to Reefs conservation planning effort to over 13,000 people. Now, more than 25 communities from Isabel and 34 communities from Choiseul have adopted community conservation areas based on these plans.

Extending Gender Equity to Papua New Guinea

James’ project also extends to Manus, Papua New Guinea (PNG), the Conservancy helped develop the country’s first network of tribal leaders, known as the Mwanus Endras Asi Resource Development Network. This network links more than 100 tribal chiefs who want to sustainably manage their natural resources. But the network is male-dominated, which would leave women, their needs, and their skills out of big decisions about their resources.

James is working with the Conservancy’s PNG field staff and local women leaders to support a women’s arm of the tribal network, called Piliapan, where women identify their own goals and activities to strengthen their livelihoods and lead to better conservation outcomes.

“Those of us who are leading make sure women are there, so we have the chief system and we have the women leadership system incorporated into that same network,” says Piwen Langarap, coordinator of the women’s arm of the network.

To better understand the existing gender roles in these communities, James will develop a baseline people survey and then train women from the local communities to collect data from across Manus province. “Even just training the women to collect the data is amazing,” says James. “It’s always been the men or outsiders who conduct these studies, so having women gather and manage the data will be a change in itself.”

Embracing Cultural Change

Justifying cultural change is something James often has to address when discussing her work on gender.

“People will often use the cultural argument as a reason not to change, but culture is not static, it’s evolving.” says James. “It’s not bad for culture to change if it’s changing for the better, keeping the great things and discarding inequality, but understandably it’s the most powerful people that don’t want it to change.”

Trickle-down changes from James’ and the Conservancy’s work are already noticeable. Historically, women only attend a conservation or natural-resource management meeting to cook for the men, unless someone like the Conservancy advocates for them to be included. But women’s networks in the Solomons and Papua New Guinea are both empowering women to take part and exposing the men to just how valuable womens’ input is to resource-management decisions.

“I’m seeing change much more quickly than I ever would have thought,” says James. “Women are really starting to be recognized as decision-makers and there are so many great men across both countries supporting these achievements.”

Dasipio was recently elected as a chief in the Kia community, reinforcing the often-neglected matrilineal chief system. More than 15 women have been elected as chief in Isabel since 2012, a trend that Dasipio largely credits to the Conservancy helping men realize the capacity and skill of women. James says that the Paramount chief of Isabel is also highly supportive of both conservation and women’s involvement.

“For 100 years Isabel women didn’t know anything we just stayed and the men take over the role of resource ownership until the Conservancy came in and helped us.” Dasipio says. “Before we just woke up and saw that some of our resources are already gone, but now we are trying to restore them again.”

Hi

Im writing from Cameroon and i am impressed with your write up trying to explain the equality in gender as concerns conservation.But please can you drill me on some encouraging and convincing article to deliver to the rural woman for her to better understand the importance of conservation to her and her environment as a whole?

Hello,

I loved your article and I believe your thoughts about gender are right on target. As a woman I am wondering what I can do for nature conservancy in the Central Florida area. I am very desirous of stopping black bear hunting but I am also beginning to worry about our water here. Would love to hear your thoughts.