Conservation organizations often use charismatic species to help fundraise for nature protection, but this approach can bias funding towards the species people know and love. New research from Nature Conservancy scientists provides a science-based way to identify flagship species that maximize global biodiversity conservation.

The Gist

The research, published in Nature Communications, provides a science-based method that organizations can use to select flagship species for fundraising campaigns in a way that maximizes biodiversity conservation.

Jennifer McGowan, a spatial planning scientist at TNC and lead author, explains: “Our method identifies the places that are most valued for particular conservation benefits — biodiversity, carbon, or other ecosystem services — and then makes sure there is a charismatic flagship species in that location that can be used to fundraise for its protection.” Surprisingly, this is the first time that science has been used to underpin the selection of flagship species for marketing alongside global biodiversity prioritization.

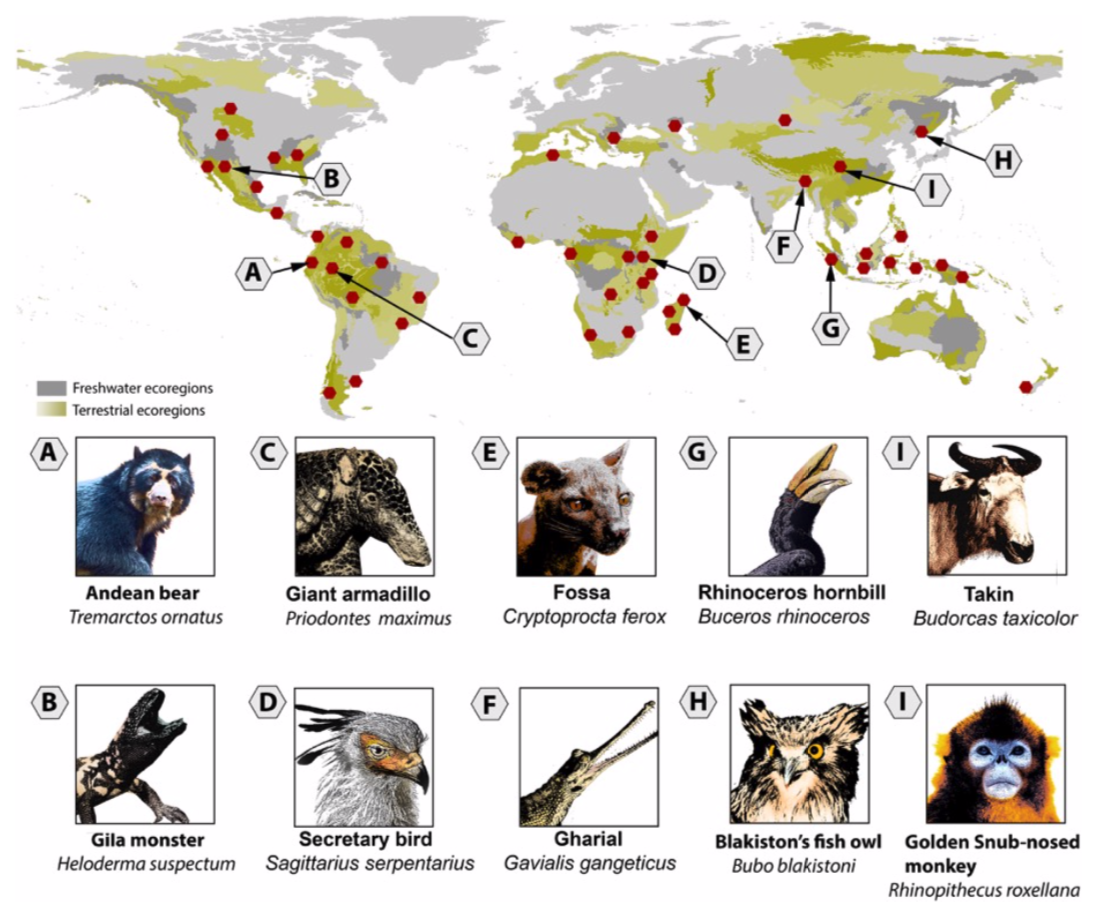

The study uses a group of potential flagship species identified in previous research on “Cinderella species” by co-author Bob Smith, from the University of Kent, as well as data from Oxford University that uses Wikipedia to gauge public interest in different species. Together, those sources generated a list of 800 potential flagships, including many species that may be unfamiliar. Examples include the takin, a large Himalayan ungulate, or the red-eared guenon, a forest-dwelling monkey in west Africa.

McGowan then merged data on protected areas, the distribution of human impacts, and the ranges of over 19,000 species worldwide to identify the most efficient network of places that represent global terrestrial and freshwater biodiversity. She then combined both sets of data into a custom framework that identifies priority places for conservation that have a flagship species to help maximize fundraising efforts.

The Big Picture

Conservation organizations frequently use flagship species in their marketing and fundraising campaigns. “But this tactic is often heavily criticized for biasing funding solely towards the species that people like — usually large, charismatic animals — and their habitats,” says McGowan, instead of funnelling money to the places or species that need it most.

Critics often argue that more biodiversity is protected when fundraising campaigns focus on protecting biodiverse places instead of single charismatic species.

What’s more, McGowan says that organizations that use flagships don’t usually have a systematic or science-based way of selecting which species to highlight. Wanting to avoid this problem, Conservation NGO WildArk asked McGowan to devise a science-based way for them to choose flagships that would represent biodiversity writ large.

The Takeaway

Flagship species campaigns will continue to play a role in conservation marketing, fundraising, and branding.

“Resources for conservation are limited, so it’s essential that we find science-based ways to select flagships, rather than framing our approach around what’s popular or seen as ‘cute’ by the public,” says Hugh Possingham, chief scientist of The Nature Conservancy. “Everything can be quantified and used for rational decision-making, even an animal’s charisma.”

This research shows that it’s possible to use flagship species to leverage funding for vulnerable ecosystems, if those species are chosen correctly. “It’s time for us to put some science behind the species we use to market and fundraise for conservation,” McGowan says.

Dear Justine,

You are to be commended for addressing this issue. I believe the Nature Conservancy is correct in its approach and I have greatly reduced my contributions to the “panda group” and removed it from my will. I always enjoy your essays. I am a retired biology professor and applaud the science-based policies of TNC.