A new database of global seabird restoration projects allows scientists to analyze trends and provides a tool for practitioners looking to effectively restore seabirds and coastal ecosystems.

The Gist

Led by Dena Spatz, a senior conservation scientist at Pacific Rim Conservation, researchers built a database of seabird restoration activities from around the world. The effort, including scientists and conservation practitioners from New Zealand and the USA, sourced data from meticulous reviews of reports, peer-reviewed literature, conferences, and social media, as well as write-in submissions and conversations with hundreds of seabird experts. Analyses of these data allowed them to examine global trends in seabird restoration activities and outcomes, the results of which were published in the Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences.

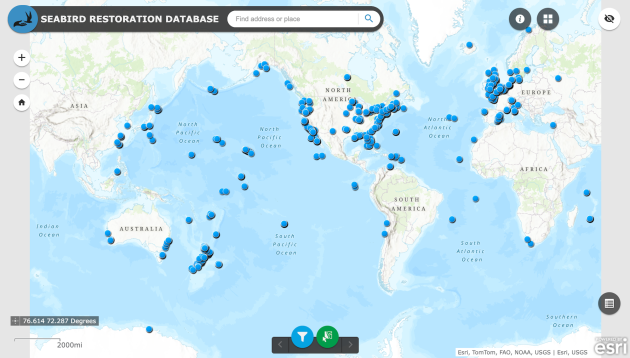

As of 2023, the researchers documented 851 restoration activities in 551 locations targeting 138 seabird species. They found that target species visited the site in 80% of the restoration efforts, and breeding occurred at 76% of project sites within two years of project implementation, on average.

“While approximately a third of all seabird species were targets of restoration efforts,” says Spatz, “we found that global trends were influenced strongly by tern restoration using social attraction, a method which mimics the feel of a seabird colony by using decoys or sound lures to attract birds into a restoration site.”

Efficacy was also high for species like petrels and shearwaters, especially when social attraction was paired with translocation. Yet unlike terns, these species took longer to respond to restoration, due largely because they tend to breed at an older age. The researchers recommend that future seabird restoration projects, particularly those targeting these species, budget five years before success is evaluated.

The Big Picture

Seabirds are the most threatened bird group, with approximately 30% of the 360 seabird species at a heightened risk of extinction. One of the greatest threats to seabirds are invasive mammalian predators, like cats, rats, and foxes, that were introduced to islands where they breed. Decades of conservation efforts have focused on eliminating these predators, with high success rates. But seabird populations don’t always recover. If absent from a breeding site for too long, the birds lose their generational memory and are unlikely to return on their own.

Conservationists are increasingly turning to social attraction to lure birds in and encourage them to breed. Tools like plastic bird decoys, sound systems playing bird calls, mirrors, and even translocation of live birds are all being used, with varying levels of success.

Each of these techniques has proven successful, but their efficacy varies with different seabird species. And limited conservation funds and declining populations leave little room for trial and error. The seabird restoration database systematically crowd-sources research to provide important and timely lessons learned to guide future restoration efforts.

The Takeaway

Analysis of the Seabird Restoration Database demonstrates the efficacy of seabird restoration. But it also shows that successful restoration takes time, something that Nick Holmes, lead for The Nature Conservancy’s Island Resilience Strategy, says is influenced by the breeding ecology of each species. “Funders, land-owners, and all partners involved must understand the time it will take to see results, and this is taxa dependent,” she says. “But importantly, we know the likelihood of positive results is very high, so investment into longer-term projects can be well informed by these results.”

The research also highlighted areas where additional conservation work is needed. The analysis found that six countries (including territories) accounted for 80% of all restoration events: the United States, New Zealand, the United Kingdom, Mexico, Canada, and France. Just 1% of restoration events occurring in lower-middle and low-income countries, and only 6% occurring in Small Island Developing States.

Spatz and her colleagues see this publicly available tool as supporting a call to action, enabling practitioners to pursue new restoration projects, and give future efforts the best chance of success.

The following organizations developed the database and created the Seabird Restoration Database Partnership: New Zealand’s Department of Conservation, Museum of New Zealand Te Papa Tongarewa, National Audubon Society, Northern Illinois University, Pacific Rim Conservation, & The Nature Conservancy.