A new paper by an international group of researchers, including scientists from The Nature Conservancy, points to areas where conservation and sustainable management can provide 90 percent of nature’s contributions to people and meet biodiversity goals.

The Gist

Loss of natural ecosystems poses well-established threats to both biodiversity and human wellbeing. Often, conservationists address these threats as separate issues, but new research argues that governments, agencies and non-governmental organizations must find ways to address more than one challenge at a time.

New research, published in the journal Nature Communications, finds that conserving about half of global land area could maintain nearly all of nature’s contributions to people and still meet biodiversity targets for tens of thousands of species. But more than a third of priority areas are at risk of conflict with human development.

“Biodiversity, climate, and sustainable development cannot be considered in isolation,” said lead author Rachel Neugarten at the Cornell Lab of Ornithology. “We must also factor in nature’s contributions to human well-being, including clean water, carbon storage, crop pollination, flood mitigation, coastal protection, and more.”

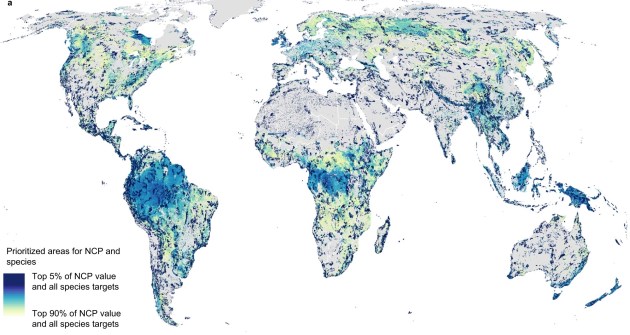

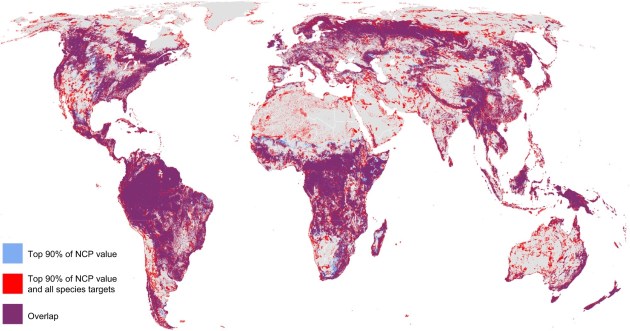

The new study is based on a global-scale optimization that identifies places important places for both biodiversity and nature’s contributions to people.

Study authors considered which ecosystems provide ten important benefits to people, including carbon storage, sediment reduction, coastal protection and access to recreation, among others. They found that roughly half (44-49%) of global land area, excluding Antarctica, provides nearly all (90%) current levels of nature’s contributions to people while also conserving biodiversity for 27,000 species of birds, mammals, reptiles, and amphibians.

But the findings also point to potential conflict, because 37% of the land areas are highly suitable for development by agriculture, renewable energy, oil and gas, mining, or urban expansion.

The Big Picture

Under the Kunming-Montreal Global Biodiversity Framework (GBF) over 200 countries have made commitments to conserve at least 30 percent of global lands and waters. Another proposal, popularized by the late biologist and author Edward O. Wilson, calls for conserving half the earth.

Based on a global-scale optimization of land uses, this study identifies joint priorities for biodiversity and nature’s contributions to people. The findings support such commitments while emphasizing the importance of integrating biodiversity, climate and development goals. Unfortunately, coordinated planning remains rare.

For instance, achieving renewable energy goals could come into conflict with nature conservation goals. But researchers argue it does not have to be this way. Through science and tools, such as Site Renewables Right and Global Renewables Watch, The Nature Conservancy is helping to identify the best places for renewable energy while protecting natural lands.

The Takeaway

With such high conflict potential and only 18 percent of the necessary land area protected, diverse stakeholders – governments, companies, funding agencies, conservation NGOs, and local communities – must work together to find solutions.

“Accelerating strategic, inclusive and proactive spatial planning is urgent and required under the GBF,” says Christina Kennedy, co-author and TNC’s Global Director of Spatial Conservation Science. “We must plan across a range of social, cultural, and environmental objectives and create integrated land/seascape plans to get ahead of potential conflicts and provide timely and equitable solutions. This was the motivation behind TNC’s joint development of the Marxan Planning Platform (MaPP), an open-source spatial planning platform designed to scale up collaborative, science-based decision-making about the allocation of limited conservation resources where they matter the most.”

The study offers a starting point to identify global targets and broad priority regions for conservation and sustainable use investments. The researchers build on a history of efforts to define global biodiversity hotspots by adding two important new considerations: the diverse contributions of nature to people and potential conflicts with expansion of agriculture, energy, extractive industries, or urban development projects.