Australian scientists estimate that invasive wild pigs release the emissions equivalent of more than 1 million cars per year via soil disruption as they forage. The study is the first-ever global analysis of the ramifications of invasive species on carbon emissions.

The Gist

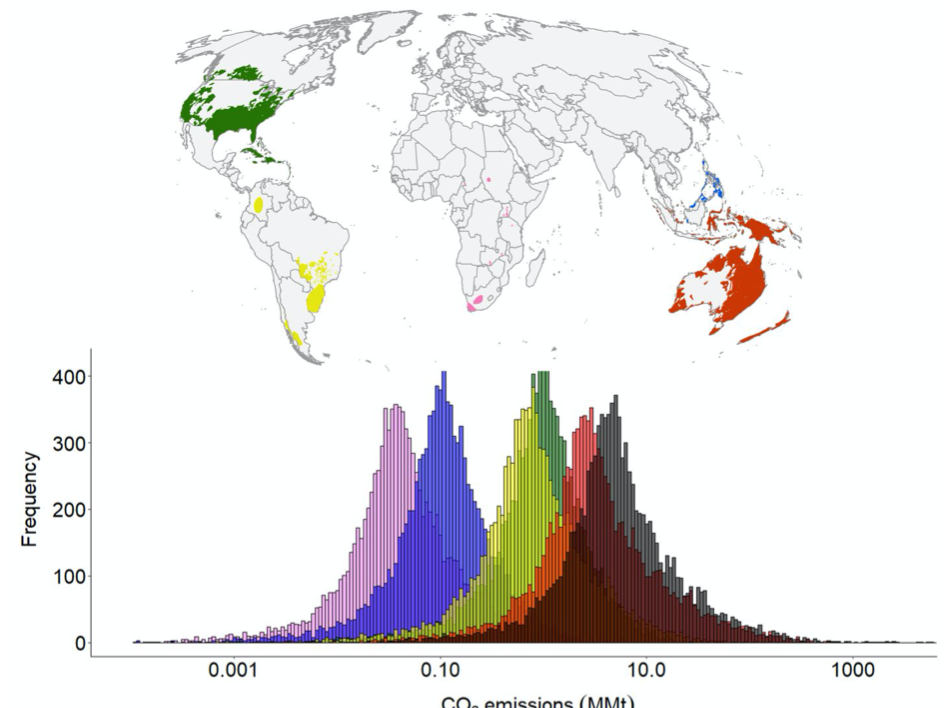

The researchers used models of wild pig population density to predict soil disturbance and resulting carbon emissions from invasive wild pigs. They estimate that wild pigs are uprooting a median area of 36,214 square kilometers per year, an area the size of Taiwan. The resulting soil disturbance causes a median emissions estimate of 4.9 million metric tonnes of carbon-dioxide per year, which is equivalent to the annual emissions of 1.1 million passenger vehicles.

The Big Picture

Wild pigs (Sus scrofa) are one of the most widespread and abundant invasive mammals in the world. The species is native to Europe, Asia, and Southeast Asia, but thanks to human introduction pigs are now found on every continent except Antarctica.

“Wild pig feeding behavior is analogous to a tractor ploughing a field, turning over soil in search of plant parts, fungi, and invertebrates,” says Christopher O’Bryan, a postdoctoral researcher at the University of Queensland and lead author on the paper. “Carbon is stored in soil, which can be released in the form of carbon dioxide when disturbed through a process called oxidation.”

The majority of Earth’s terrestrial carbon stores are locked up in soil. Scientists have a good understanding of how much soil carbon is lost through various human actions, like agriculture or urban development. But we know far less about how invasive species contribute to carbon emissions, either through loss of soil carbon or vegetation carbon stores.

The Takeaway

This research is the first-ever global analysis of the impacts of an invasive species on carbon emissions.

The researchers acknowledge that their carbon emissions estimate is highly uncertain — with a 95 percent prediction interval of 0.3 to 94 MMT CO2 — due to variability in wild pig density and soil dynamics. O’Bryan says that’s to be expected for a global-level analysis, because of the uncertainty associated with estimates of wild pig densities, wild pig behavior, and variable soil dynamics.

“There are alternate dimensions to the climate problem that we haven’t considered, such as invasive species, with dramatic co-benefits of their management that are well known, like biodiversity protection and food security,” says O’Bryan.

Like any complex decision process, O’Bryan notes that it is important to assess the costs and benefits of management decisions. “While we can see potential benefits, wild pigs are very costly to manage and it can have variable results,” he says. “The next key step is to take a more holistic approach and investigate the trade-offs of managing wild pigs to achieve multiple objectives.”

A very interesting article as I’ve been involved in feral hog research and management since about 1970, mostly in Florida. Despite their bad reputation, they’re a very interesting animal in many ways. In some areas of our state we have densities of about 50 +/- per square mile. Texas has more feral hogs, but only because the state is larger and their carrying capacity is not as great.