The U.S. is investing billions of dollars to reduce forest fire risks. New research maps the hot spots where investments in strategic forest management could offer the biggest payoff for people and climate.

The Gist

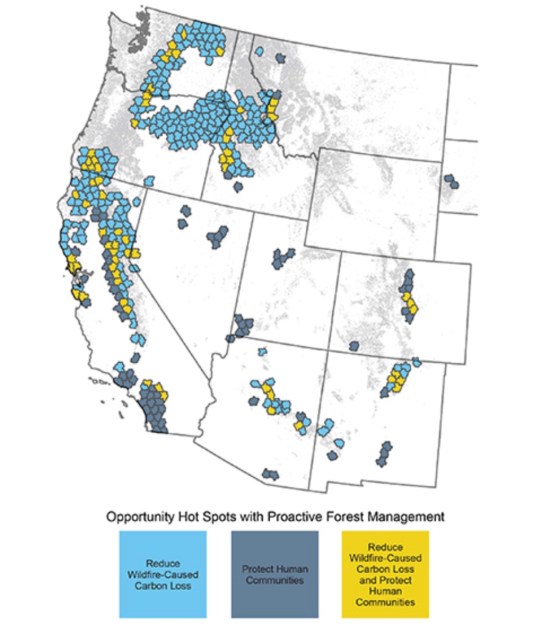

Published in Environmental Research Letters, the study, a collaboration among The Nature Conservancy, University of Montana and USDA Forest Service, estimated the risk of wildfire-caused carbon loss across the conifer forests of the western United States.

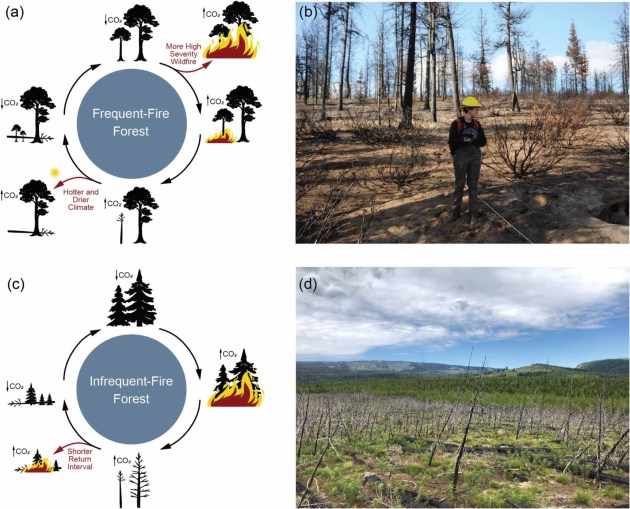

Researchers then compared areas identified as at risk for carbon loss to wildfire to human communities also vulnerable to wildfire (as identified in the Forest Service’s Wildfire Crisis Strategy.) The overlap showed high value “opportunity hot spots” where forest management tools, such as thinning, prescribed fire and cultural burning, could reduce risk from wildfire to both carbon storage, and human communities and infrastructure.

The Big Picture

The paper notes that decision-makers do not necessarily need to choose between climate- and wildfire-mitigation goals. While the study covers 11 Western states, says co-author, Travis Woolley, forest ecologist for TNC in Arizona. “The need for strategic forest management in California, New Mexico and Arizona is particularly urgent, given that a large portion of their forests are highly vulnerable to wildfire-caused carbon loss.”

“Our approach can help land managers plan where to invest in proactive forest treatments with the most potential to protect communities,” says lead author, Jamie Peeler, landscape ecologist and NatureNet Postdoctoral Science Fellow with the University of Montana. “It also could be applied to reduce risk from wildfire to other important values such as municipal water, culturally important plants, recreation and wildlife habitats.”

The paper emphasizes that, though “risk-informed prioritization maps can identify target geographies, they do not account for complex social, ecological, political, and economic dynamics occurring locally.”

The maps, therefore, are not intended to replace local knowledges or values that ultimately inform proactive forest management. Rather, they could inform and help prioritize investments in community-based collaborations that plan, implement, and maintain treatments. Ideally, note the authors, community-based collaborations represent people and agencies that reside in a particular place and share a collective interest in its well-being. The authors also highlight the importance of community involvement in any forest-management planning.

The Takeaway

Congress recently passed the Infrastructure Investment and Jobs Act (IIJA) which includes a “Wildfire Crisis Strategy” to dramatically increase the pace of forest restoration across the West. The plan includes unprecedented levels of funding ($3 billion dollars) from the federal government to reduce fuels in fire-adapted forests across 50 million acres of forests in the next 10 years which is at least two times more than current rates.

“This type of science collaboration,” noted USDA Forest Service Chief Randy Moore, “strengthens our efforts to support land managers in designing and implementing effective projects with multiple benefits, making good work even better. It also is key in informing our overall efforts to address the wildfire crisis facing our nation’s forests by doing the right work, in the right place, at the right time.”