A new scientific review argues that forests play a far greater role in protecting people from climate change than previously recognized. The study, published in the journal Science, reveals that forests not only store carbon, but they also help regulate local climates by lowering temperatures, shaping rainfall patterns, and buffering communities from floods and extreme heat.

The Gist

A team of researchers synthesized hundreds of studies to understand how forests regulate climate across local, regional, and global scales. Their conclusion: forests are powerful climate adaptation tools—not just carbon sinks. Their results were published in the journal Science.

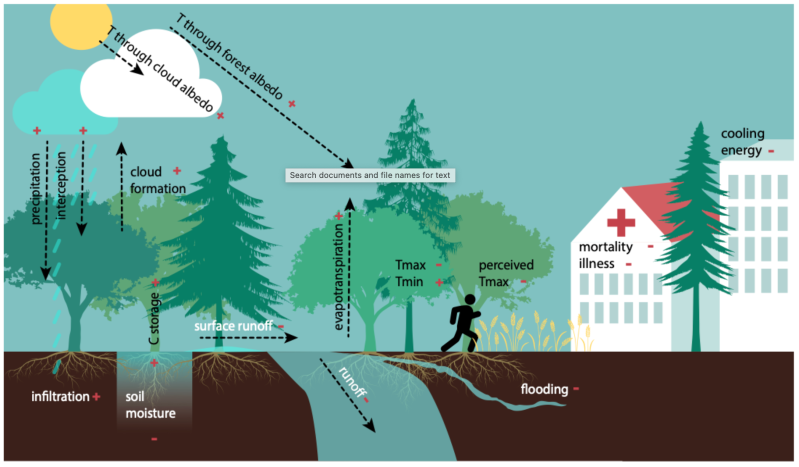

Forests reduce local daytime temperatures; this cooling is strongest in the tropics but occurs across all forest types. Their influence on water cycles is equally significant: trees add moisture to the atmosphere, help drive downwind rainfall, and shape soil water storage, groundwater recharge, and streamflow.

“Forests shape our climate in ways that are both powerful and surprisingly complex,” says Susan Cook‑Patton, a lead reforestation scientist at The Nature Conservancy (TNC). “There are some places where forests can actually contribute to global warming and provide local cooling at the same time.”

During the day, most forests cool the air below their canopies through shade and the surrounding environment through evapotranspiration. At the same time, their dark canopies absorb solar radiation and release heat—an effect that in some regions can be strong enough to counteract the cooling benefits of carbon storage.

The Big Picture

The presence or absence of forests can have life‑or‑death implications, especially for people living in the tropics. The authors note that intact forests can reduce local maximum temperatures by more than 4°C on average globally, with cooling exceeding 6°C in tropical forests, which in turn can help cut heat‑related mortality and protect workers from dangerous conditions.

The loss of tropical forests has already reduced safe working conditions for millions. Large‑scale deforestation drives extreme heat that spreads beyond cleared areas, contributing to thousands of heat‑related deaths each year. Meanwhile, downstream declines in rainfall threaten agricultural economies—such as in the Brazilian Amazon, where forest loss could erase nearly US$1 billion annually in crop revenue. A recent report from the United Nations Food and Agriculture Organization, TNC and other institutions synthesizes the myriad benefits of forests for agriculture.

The Takeaway

The research arrives at a moment when governments and companies are pouring billions into forest‑based climate solutions, with an overwhelming focus on forest carbon. This paper demonstrates that a carbon-only approach overlooks critical trade‑offs—and enormous opportunities—for the power of forests to improve human well-being.

Policy makers can maximize the benefits of forests by prioritizing native forests protection. Old‑growth forests, in particular, have unmatched capacity to buffer temperatures and regulate water with fewer ecological downsides than plantations or non‑native species. In many regions, old-growth forests offer some of the most cost‑effective climate solutions available.

Restoration efforts should be done strategically, focused on areas where trees naturally thrive—not in drylands where planting can deplete water supplies or cause unintended warming. And expanding canopy cover in cities can reduce heat‑related deaths, lower energy use, and improve public health.

“When we talk about forests and climate, we often focus on carbon storage, but forests are also protecting millions of people from heat stress right now by reducing temperatures, improving working conditions, and potentially preventing heat-related deaths,” says Dr. Luke Parsons, an applied climate modeling scientist at TNC. “The challenge is that these benefits depend entirely on context. What works in the Amazon may not work in a semi-arid savanna. We need nature-based climate solutions that are tailored to local ecology and the needs of local people.”