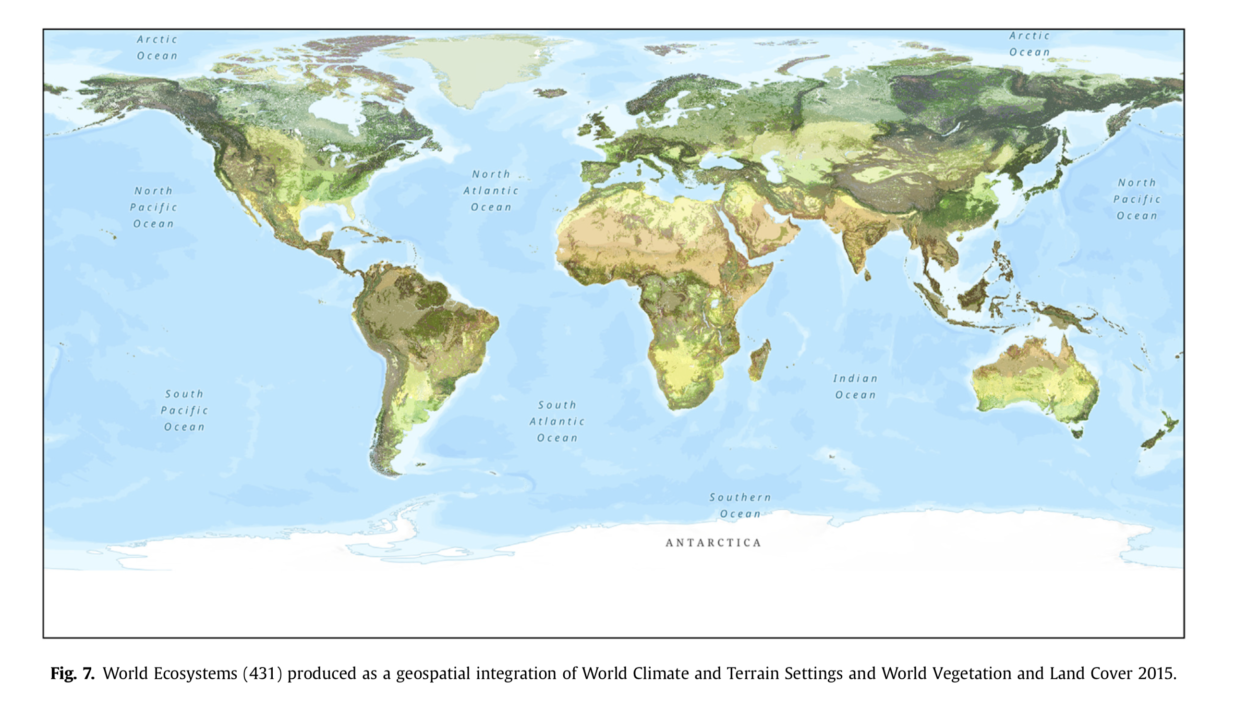

Protected areas are the foundation of modern biodiversity conservation, but their effectiveness hinges on how well they represent all of the world’s ecosystems. Scientists have created the first standardized, fine-scale map of global ecosystems, allowing them to better measure the effectiveness of protected areas and identify ecosystems in need of additional protection.

The Gist

A team of international scientists created the first fine-scale map of global ecosystems. Their map combines the most recent and robust global data on climate, topography, vegetation, land use, and biogeography to identify more than 1,242 natural ecosystems.

“This resulted in a much more diverse tapestry of global ecosystems than the previous default for assessing global conservation needs,” says Nicholas Wolff, a climate change scientist at The Nature Conservancy and author on the paper, which was published recently in Global Ecology and Conservation.

Next, the researchers analyzed how well each of these ecosystems are represented in the current protected estate. The Convention on Biological Diversity Aichi 11 Target mandates that countries protect 17 percent of their terrestrial area by 2020. The research team found that one-third of ecosystems had met this target, and an additional one-third were more than halfway to the target.

The Big Picture

Global biodiversity is in crisis, with extinction rates hitting unprecedented levels for all taxa. Protecting ecosystems is the best way to save species, and so global conservation priorities all focus on protecting a certain percentage of the world’s ecosystems.

But how scientists define and map those ecosystems has a massive influence on the effectiveness of protected area networks.

The previous default mapping system, called ecoregions, uses more coarse and high-level data, and thus fails to capture fine-scale ecosystem diversity within these larger regions. As a result, protected area networks built on ecoregion maps risk missing important ecosystems.

The Takeaway

Standardized, data-driven maps are critical to track progress on conservation targets and identify ecosystems that are under-represented in the protected area network. “Representation is the most important principle of protected area planning,” says Hugh Possingham, chief scientist at TNC and co-author on the research.

He explains that the Aichi 11 target mandates 17 percent protection, but it doesn’t stipulate what ecosystems should form that 17 percent. Countries could meet their targets and still fail to protect biodiversity if their protected areas don’t contain equitable examples of every kind of ecosystem.

The global conservation community will meet in October 2020 to establish the next set of conservation targets. “We hope countries will use this approach to map their ecosystems at a much finer level to help ensure their protected area networks really do protect all ecosystems,” says Tim Boucher, a conservation geographer at TNC and co-author.

And unlike ecoregions, this new approach can also be used to model how climate change will alter different ecosystems over time. “We can see which ecosystems are at most risk of disappearing altogether,” adds Wolff, “or which areas will offer refugia for ecosystem persistence.”

The article is unclear as to what constitutes an ecosystem mapping on such a global scale- by habitat or species threat ?