The boat emerges from a wall of fog into a magical scene. Pods of dolphins swim in our wake. Several humpback whales spout nearby. Flocks of Wilson’s storm petrels – small sea birds – fly all around us. We take a moment to take it all in. Then it’s time for action.

Carl LoBue, oceans and fisheries director for The Nature Conservancy in New York, stops the boat and begins gently providing directions. Marine sciences teacher Kimberly Williams (and also Carl’s spouse) is already digging around for gear. Researcher Juliet Lamb stands ready with the net.

And I’m bent over a cutting board dicing menhaden, an oily fish that will serve as chum.

At a glance, it looks like we’re on one of the many tuna sportfishing boats that ply these waters. But we’re not after fish. We’re seeking seabirds. Specifically, shearwaters.

We’re 70 miles offshore of Long Island, with a plan to net and then tag great and Cory’s shearwaters. These pelagic bird species nest in the South Atlantic but are common visitors off the Atlantic Coast in summer months. While the basics of their life histories are documented, there are a lot of gaps. This project aims to fill in some of that missing information by tracking their movements, which in turn could help inform fisheries management and offshore wind development.

As our boat drifts, a small flock of great shearwaters bobs in the water off the boat’s bow. I begin flicking chunks of oily fish over the boat. LoBue meanwhile grabs a fishing rod, rigged with a hookless fishing lure. The idea is that the commotion caused by the skittering lure will attract the shearwaters’ attention, and they’ll follow it to the bait.

Then they’ll be attracted to the bait. While they’re intently feeding, Juliet Lamb will drop a net over the nearest bird. That’s the idea.

LoBue casts out the plug and it hits the water with a loud splash. The shearwaters take one look and then flush, flying far away.

“Well, that plan didn’t work,” LoBue says with a bit of resignation.

It turns out, a lot of plans don’t work in seabird research. This project, which aims to track the movements of a number of nearshore and offshore birds, involves trial and no shortage of error.

“There’s always an element of improvisation out here,” says Lamb, who specializes in seabird research. “You need to be able to adapt and improve.”

What Seabirds Can Tell Us

Juliet Lamb knows the trials and rewards of seabird research well. She’s spent her career working with these birds, the past 2.5 years with The Nature Conservancy. This summer, she’s tagged northern gannets, terns, oystercatchers, gulls and pelicans – each posing their own challenges.

“Seabirds are really good indicators of what’s going on in the marine environment,” says Lamb. “Seabird expertise can contribute to knowledge important in a number of marine conservation issues, including fisheries management and offshore wind development.”

Offshore wind resources are being rapidly developed in the eastern United States, important to providing clean energy. There are 15 commercial offshore wind lease areas located off the eastern U.S. coast, with others planned for California and Hawaii. A report commissioned by TNC found that turbines can actually create habitat for fishes and other marine life, particularly if they incorporate nature-based designs. But what are their impacts on seabirds?

“The leases on the East Coast were approved years ago,” says LoBue. “We’re gathering information that can inform how you build them or where you micro-site them within leases could minimize impacts. And how future wind developments can be sited in a way to maximize benefits while minimizing impacts on wildlife.”

To do that, the research effort is attaching solar-powered satellite tags to a variety of bird species, allowing them to be tracked throughout the year. “For species like shearwaters, we know where they nest and their migration routes,” says Lamb. “But we don’t much about what they’re doing while they’re here.”

Lamb and LoBue are both quick to point out that, while wind energy can have impacts, it is not the major threat to seabirds.

“The major threat to these birds is climate change,” says Lamb.

She then lists the variety of ways climate change threatens the birds she studies. Sea-level rise inundates the low-sandy islands and beaches favored by nesting terns and gulls. It changes the movement of the birds’ prey species. Vegetation changes can expose chicks to predators. The chicks can also overheat or be more prone to disease.

“We want to use this research to understand the birds and their needs better,” Lamb says. “The info we can gather can be used to answer a lot of different questions, including about how to best site wind energy.”

Sparkly Hats and Looney Tunes Traps

Lamb joined us on Long Island after spending time tagging gulls and terns on Great Gull Island at the eastern edge of Long Island Sound. More than 40,000 breeding birds utilize the island each summer. Tagging those birds lacked the unpredictability of offshore species like gannets and shearwaters, but still offered unusual adventures.

The birds were caught at the nest; when the bird is away the researchers would prop up a box with a string attached. “It was like a trap you’d see in Looney Tunes,” says Lamb. “When the bird would return, we’d pull the string and catch it.”

Due to biosecurity concerns, the researchers wore silver Tyvek suits. And to protect their heads against diving terns, they wore protective hats. Eventually, they settled on sparkly cowboy hats with flowers as the best to deter painful pecks while also adding a bit of flair.

“We’re out there amongst all these birds and we look like Mary Poppins on Mars,” says Lamb.

She also tagged brown pelicans, captured via a telescoping fishing rod with a loop at the end. Since young pelicans will regurgitate their food when captured, the researchers were also recording the birds’ diet.

“I’m partial to the pelicans,” says Lamb. “They’re so big, it takes multiple people to work with them.”

A life of adventure and birds can sound like an adventurous dream job. But it’s also grueling and tedious – especially when dealing with offshore species.

The Great Shearwater Chase

On the morning of my shearwater-tagging outing, we meet at 4 a.m., with LoBue and Lamb going through piles of equipment and double checking weather reports. There’s a sense of urgency to the day, as the weather reports for the rest of the week look sketchy. You can’t work 70 miles offshore in heavy wind.

We head out, bouncing along the waves as I fight a bit of game-day anxiety. For a writer on trips like this, it can feel a bit like being a “wildlife research tourist,” there for the adventure as researchers check and recheck equipment, navigate and record details.

I didn’t want to get in anyone’s way, especially given a lack of experience on offshore boats. I didn’t want to stumble on waves when the team was trying to catch an elusive bird. I also didn’t want to barf on the deck.

I kept these fears at bay as LoBue slowly motored us through fog. About 40 miles of fog. The sightseeing options were somewhat limited but at least I didn’t feel queasy.

And then, just like that, we came out of the fog to the idyllic scene before us. The wealth of wildlife was notable: sharks, sea turtles, dolphins, seabirds and whales. Lots of whales. Humpbacks surfaced around us and we caught regular glimpses of minke whales and even a fin whale.

“Where are the shearwaters?” LoBue wondered aloud.

They could be seen circling the whales, but not in the number LoBue and Lamb had hoped.

Shearwaters have tubular noses that enhance their sense of smell. Their name refers to their wings looking like they cut or “shear” the water as they fly over it. They’re beautiful birds, especially up close. But few were letting us get close.

And when we would, they’d fly off well before Lamb could deploy the net. The chum slick – oily fish bobbing in the water – seemed to hold little interest to small flocks.

So we cruised searching for a bigger aggregation of birds. In the meantime, we helped out a whale research crew from the Wildlife Conservation Society, keeping tabs on humpback whales for them. LoBue called it “whale sitting.” There are far worse ways to spend a day, but I also recognized the pressure the researchers felt.

More than 100 birds of different species would be tagged this summer, but as of yet, no shearwaters.

Finally, near the end of the day, four shearwaters bobbed calmly on the water. Lamb climbed to the bow of the boat, hoop net at the ready. LoBue slowly drifted into range, then gunned the engine. But he lost sight of the birds and, at the last minute, pulled back. He didn’t want to hit them. In the pause, the birds took to the air, leaving Lamb still holding the net. So close.

Time was winding down. We had to make the run back to shore in more fog. Still, both LoBue and Lamb felt hopeful. “We got close,” LoBue says. “We’ll get this figured out. We just need the weather to cooperate.”

As we motored back, captains from charter fishing boats checked in with LoBue. “How did you make out today?” one asked.

“Oh, we weren’t fishing. We were out here trying to tag shearwaters,” LoBue replied.

A laugh. “That’s a new one. Why would you do that?”

“It’s not my hobby,” LoBue says.

The way wildlife research is sometimes portrayed, it can seem like an adventure-filled life. And it often is. But it’s also long days, equipment maintenance, and dead ends. It’s grant applications and reports, recording data and writing papers at the end of those long days. Birds, weather or waves don’t always cooperate.

It’s not a hobby. But that hard work can pay off in gaining valuable insight into the needs of seabirds, and how conservationists can help shape a resilient future for them in the face of climate change and other threats.

A Postscript: Catch and Release

And a week after I departed, the group finally seized the first opportunity to return in search of shearwaters. This time, following reports that the birds were much closer to shore off Montauk, they coordinated with a local fisherman to take them out.

As soon as they motored around the tip off Montauk, they could see large numbers of great, Cory’s and sooty shearwaters. “It was far more than we found offshore,” Lamb says.

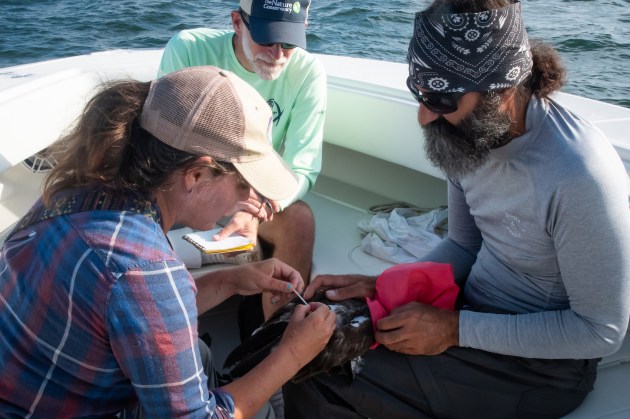

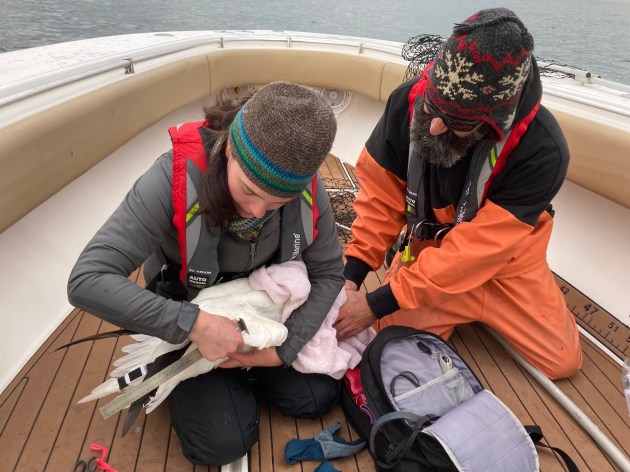

After a few warm-up passes with bait and fishing poles, TNC scientist Chris McGuire caught three shearwaters in quick succession using the hoop net. The captures went off perfectly. The birds were untangled from the net, then transferred to a cloth bag where they were weighed, measured and banded.

The team then attached transmitters using two loops of harness ribbon secured around the join where their legs met their bodies. After giving the tagged shearwaters a quick adjustment period in a soft-sided dog crate, they tossed them into the air and watched them fly off.

“We left with plenty of photos and my arms crisscrossed with thin scratches from shearwaters’ sharp bills and claws,” say Lamb.

Some of the birds tagged flew hundreds of miles away, in different directions – making it to the edge of the continental shelf.

“I check their tracks multiple times a day, imagining what they’re seeing and experiencing so far from land, completely at home in a world we only get to visit,” says Lamb. “Seabird work doesn’t always go according to plan, but when it does, it makes all the frustration worth it!”

Another fascinating story about pursuing knowledge and more understanding of bird lives! I’m just a lay person who loves to read and learn about these amazing creatures who share our planet. Thanks to you, Matt, for great writing!

Cutting chum perfect for a fisherman 🙂 This birder thanks you for sharing this cool project.

Hello. I found your research very informative. As you mentioned, very few people understand the efforts ad hard work involved in such type of work. Now that you have tagged the birds, will be be providing an update about their movements? Thanks.